Descent to Xibalba

Prefer to listen to this post?

Travelers, today we journey to Middle America. No, not the middle America of small towns, wingnut politics, and climate denialism (though that’s a frightful destination we really should visit someday). I refer here to the original middle America which historians refer to as Mesoamerica, the collection of cultures inhabiting the southernmost part of North America, the Yucatan peninsula, and the Pacific coast of Central America from almost 2000 BCE up until Spanish greed fucked it all up in 1519. The descendants of the these ancient cultures number around 7 million today in a mostly Westernized Mexico and Central America lucky to have them.

Why go here, you ask? Because the cultures of Mesoamerica were absolutely rad, that’s why. You like chocolate? Of course you do. Thank the Mayan civilization. Hey you texting on your phone and not paying attention to this tour, clearly you enjoy systems of writing. Thank the Olmec civilization. Wish someone would invent universal education for every member of society in the Americas? Someone did. Thank the Aztec civilization.

But this isn’t a history podcast. It’s a horror show. And boy howdy do we get some horror from Mesoamerica. We’ll start our journey in Mayan hell and work our way up to the light. Welcome to today’s itinerary of the Terror Tourist: Descent to Xibalba.

So it was that the lords of Xibalba, One Death and Seven Death, heard the ruckus and said: ‘What’s happening up there on the surface of the earth? All that stomping and shouting? It is time to summon them to come play ball down here, so that we might defeat them.’

This line comes from the Popol Vuh, the foundational creation myth of the Mayan civilization. Long story short: the twin human brothers Hun Hunahpu and Vucub Hunahpu are in fact summoned by the lords of the Mayan underworld and put through horrific tests and trials. These include a river filled with scorpions, a river filled with blood, and a river filled with pus. Once past these nasty waterways, visitors the boys are challenged to survive the homes of possibly the least desirable neighborhood imaginable: Dark House, Cold House, Rattling House, Jaguar House, Bat House, Razor House, and Hot House. Xibalba also had a ball court. Which is a nice touch.

Hun Hunahpu and Vucub Hunaphu make it through these trials, but they are murdered anyway. Hun Hunahpu’s decapitated head is put in a calabash tree. Still able to speak, the head spits on a passing woman, Blood Moon, daughter of the demon Blood Gatherer, impregnating her. She comes to the surface of the world and gives birth to twins as well — Hunahpu and Xbalanque — who, when grown, descend to Xibalba to avenge their father and uncle, defeating the lords of the underworld in a Mayan ballgame, ironically the same game whose ruckus caught the attention of the demons in the first place. Hunaphu and Xbalanque are transformed into the moon and the sun. Thus begins the Mayan cosmogony. Lotta body fluids, lotta houses out of a Saw movie.

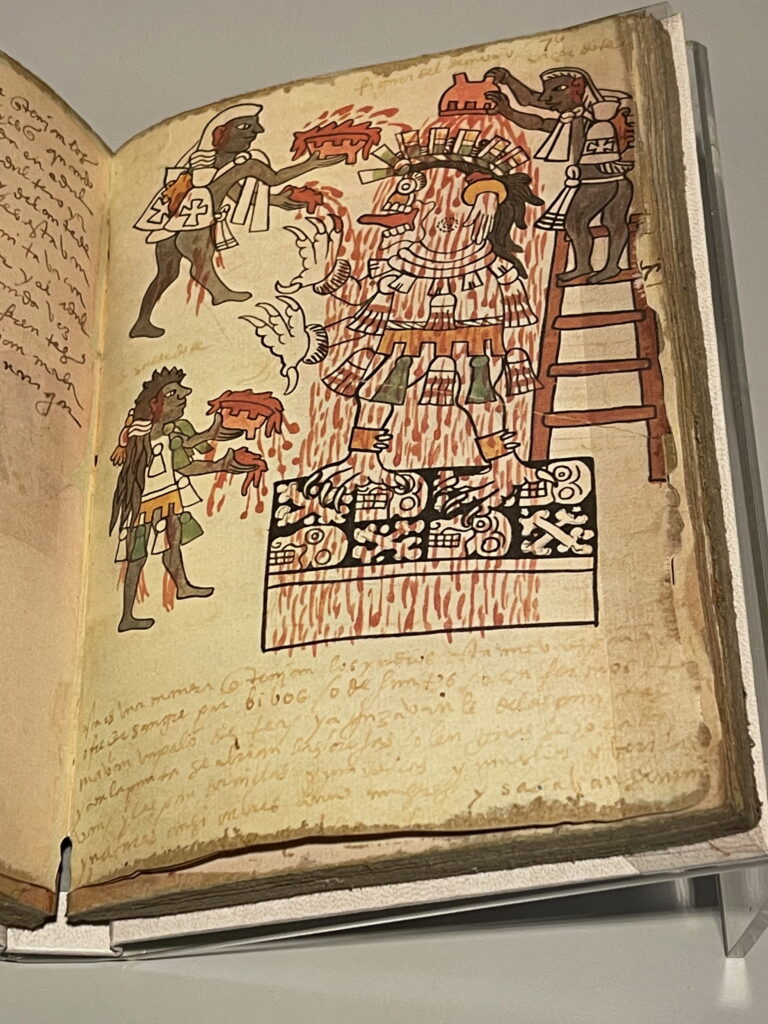

As with so many ancient belief systems, bloodletting was central to rituals surrounding legitimization of rule and cultural order. Metallurgy itself came very late to Mayan civilization, so blood was drawn using implements made of obsidian, stingray spines, or shark’s teeth. In elaborate public rituals atop pyramids the ruling elite would pierce their tongues, buttocks, and penises. The spilling blood was collected and then burned as an offering to the gods. Often this act was accompanied by ritual sacrifice, actual murder, the ultimate offering to the gods. Victims here were almost always high-status prisoners of war. The methods of their deaths, gruesome to most modern sensibilities, were tied tightly to worldmaking legends.

For example in decapitation — the “highest” form of sacrifice — the twins’ stories from the Popol Vuh would be echoed, which is why decapitations were often accompanied by a ballgame. Removal of a still-beating heart by pulling it straight out of a victim’s chest, the most common sacrifice, made absolutely clear the centrality of blood to Mesoamerican beliefs about rebirth. After smearing himself with the blood of the removed heart the priest-turned-cardiac-surgeon would shove the fresh corpse down the pyramid steps where its skin would be removed and worn as part of a dance of new life. If the victim were especially notable his innards would be portioned out and eaten.

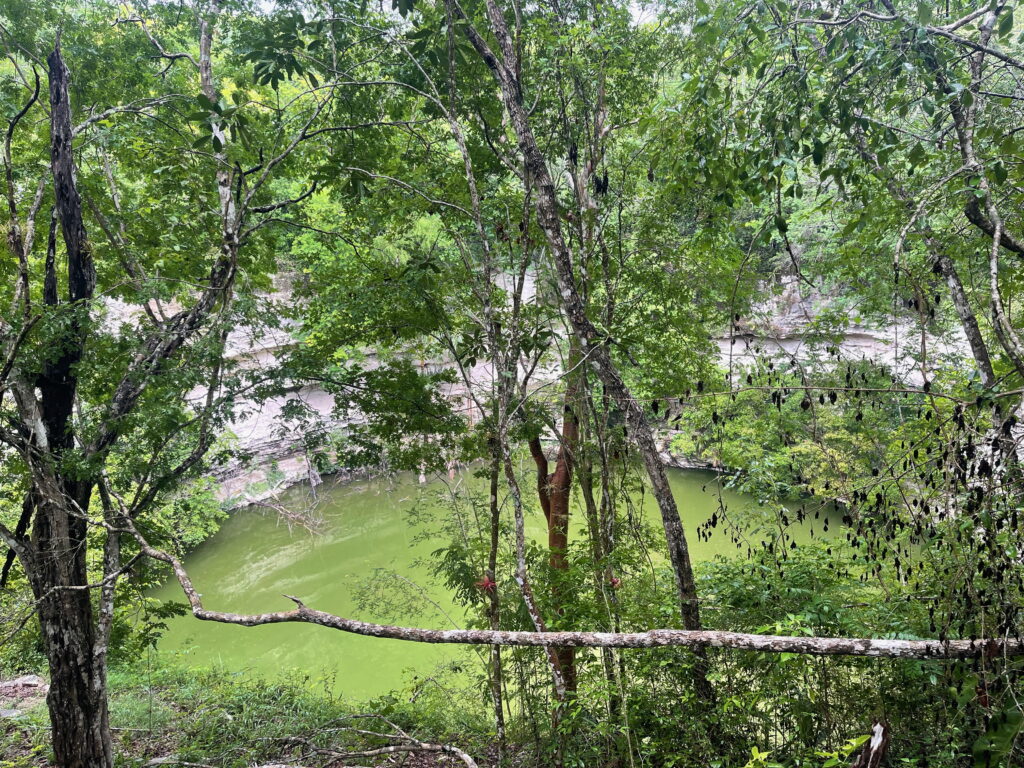

Often sacrifice was less bloody, if no less impactful. At Chichén Itzá in the Yucatán, during times of drought sacrificial victims were often tossed into the Sacred Cenote, a freshwater sinkhole, whose sheer sides meant no escape. This has been confirmed by the hundreds of skeletons excavated at the bottom of the cenote. There was also live entombment, immolation, cannibalism and, perhaps the ultimate literalization of their creation myth, binding a victim into a tight ball for ritual reenactment of the Twins’ ballgame.

In recent history the Mayans in particular have been associated with the end of the world (subject of a previous installment of The Terror Tourist). This supposed apocalypse was due to arrive on December 21, 2012 and was commemorated among other places in Roland Emmerich’s over-the-top cataclysm porn 2012. But the connection to the Mayan calendar was based on a misunderstanding. Mayan calendrics is incredibly complicated; dates are derived from two interlocking counting schemes, one linear and one cyclical, called the Long Count and the Calendar Round. The Long Count itself was divided into ages of 13 b’ak’tuns, roughly 5,125 years long. Historians backdating to a known zero date for our current age yielded the end of the 13th b’ak’tun as December 21, 2012. Thing is, the Mayans never said the world would end on this date, merely restart in a new age. Indeed almost everything about Mayan calendrics is historical rather than prophetic. They lived in the now. But hey, it was 2012 and we were twelve years overdue for a baseless global end-of-the-world panic.

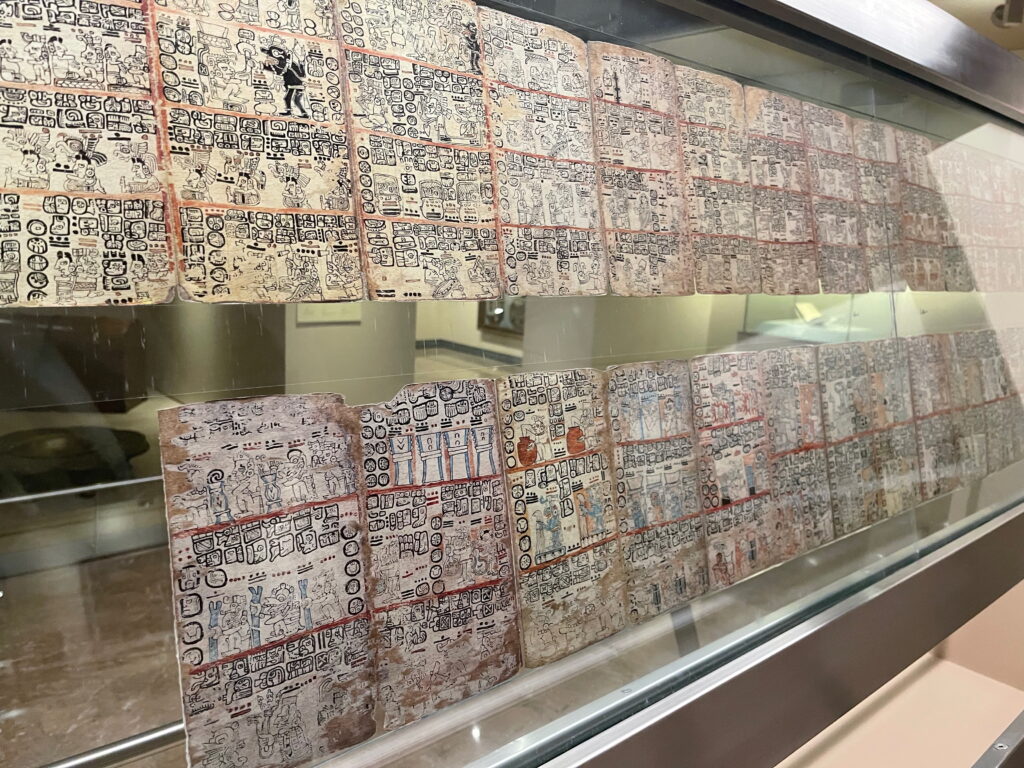

The real horror of Mesoamerica, alas, was not penis-slicing or skin-wearing or even were-jaguars. (Were-jaguars, yeah!) It was the destruction of these venerable ancient cultures by European colonizers. Starting in the early 16th century, continuing to the capture of the Aztec capital in 1519 and through to the fall of the last independent Mayan kingdom in 1697, this conquest was as much a result of war waged by the Spaniards as by the diseases they brought with them, for which indigenous peoples of the Americas had no immunity. Worse still, we have inherited comparatively little written record of these very literate societies due to the systematic destruction of their records by Christian missionaries. Only four Mayan codexes survived the Spanish flames. True Mesoamerican horror.

This relative lack of material — and the fact that Mayan hieroglyphs were not effectively decoded until the 1970s — didn’t stop Hollywood, though! In fact, it may have helped movie scriptwriters eager to fill the void of received knowledge. Can’t read the glyphs carved on that pyramid? No problem, we’ll just make something up! Let’s go to the movies, travelers.

Right at the outset we have to admit that almost all of the films noted here are prime examples of Mexploitation. Low-budget, sensational, sometimes overtly racist, with a scant if not comical understanding of actual history, these films take bits and pieces of Mesoamerican lore when useful (or more often when in synch with the current desires of the movie-going public). But they sure are fun!

Take for example, The Curse of the Aztec Mummy, maybe from 1957, maybe from 1961. It depends on how you date it and what you consider the actual movie as this has the same cast and storyline as The Aztec Mummy (sorta like Evil Dead and Evil Dead 2). Both films involve a group of scientists searching for an ancient Aztec tomb containing a mummy guarding a mythical breastplate. The mummy of course reanimates, but the real villain here is a scientific rival masquerading Lucha Libre-like known as The Bat. This is a fun watch, especially to see some of the earliest Mesoamerican tropes in film, but beware falling into this hole too deeply. There are multiple films, knock-offs, and re-cuts: The Robot vs. The Aztec Mummy (1958), The Wrestling Women vs. The Aztec Women (1964), Attack of the Mayan Mummy (re-cut of the original Aztec Mummy because, you know, Aztecs, Mayans, all the same).

Q: The Winged Serpent is exceptional monster horror from 1982. Look, if all I told you about this movie is that it involves Quetzalcoatl, the giant winged reptile, nesting inside the latticework spire of New York City’s Chrysler Building, you’d stop this podcast immediately and go watch it, right? This Larry Cohen masterpiece has all of the grit of filming permit-free in 1980’s New York. It follows a street-level crook who accidentally discovers Quetzalcoatl’s nest and then extorts the city for directions to it. You should watch this film. Also, why has no one made a sequel to this? The egg is sitting right there.

Then there’s The Laughing Dead from 1989. You’re gonna have to find this one on your own online (if you know what I mean), though there is a Vinegar Syndrome Blu-Ray available. What I saw, ironically, was a Spanish-captioned rip. Anyhoo, this one is basically incomprehensible, though the plot is basically the same as 70% of Mexploitation films: “A ragtag group of people go on an archaeological trip to Mexico to visit Mayan ruins, but get more than they bargained for, when they encounter a zealous group of Mexicans attempting to revive a deadly ancient ritual of their ancestors.” Students of Mesoamerican history will appreciate the nod to decapitation and ballgames as one victim’s head is sliced straight into a basketball hoop.

The Ruins from 2008 actually has nothing to do with ancient cultures except that it is set on top of a ruined Mayan temple — and even this was not in the original book. This is vegetative horror — basically Alien except for gardening, “The Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill” from the original Creepshow, except as a hangout movie. It’s actually a fun watch and there are some great deleted scenes and a much darker, alternate ending on YouTube. Have a watch of this one, tourists.

Squeaky actually watched and discussed Maya from 1989 recently. This is basically the same plot as The Laughing Dead with a Texas Chainsaw vibe. At least The Laughing Dead felt Mexican. This one exudes Texas. Like, why are there so many Americans running around? It’s worth a watch though for the final act which involves a Day of the Dead celebration (thoroughly Christian, but whatever) whose goal is to resurrect King Xibalba. Lots of nudity, lots of senseless gross-outs (like a guy vomiting small green snakes). I recommend.

Some optional itineraries for those who’d like to travel further:

- The Old Ways

- The Dead One

- La Llorona (2019 from Guatemala, directed by Jayro Bustamante) — not to be confused with the James Wan’s The Curse of La Llorona or the Danny Trejo The Legend of La Llorona

- Curse of the Mayans

- Curse of the Maya

- México Bárbaro

- Dolly Dearest

The truth is, there are not many exceptional Mesoamerican horror films. It just hasn’t had its day like Egyptian horror. This is in contrast to Mesoamerican horror literature, a truly thriving sub-genre. So, aspiring horror scriptwriters and directors, this material is ready for you. What are you waiting for? Make the sacrifice!

That’s it for today’s journey, my touring pals. Time to relax, maybe avoid ball courts, and put on a good movie. Until next time!

A full list of the movies mentioned above can be found at Letterboxd. Find out where to watch there.

The Terror Tourist is my occasional segment on the Heavy Leather Horror Show, a weekly podcast about all things horror out of Salem, Massachusetts. These segments are also available as an email newsletter. Sign up here, if interested. Here’s the episode containing “Descent to Xibalba”: