Maybe Shark

Prefer to listen to this post? (It’s really me, not AI!)

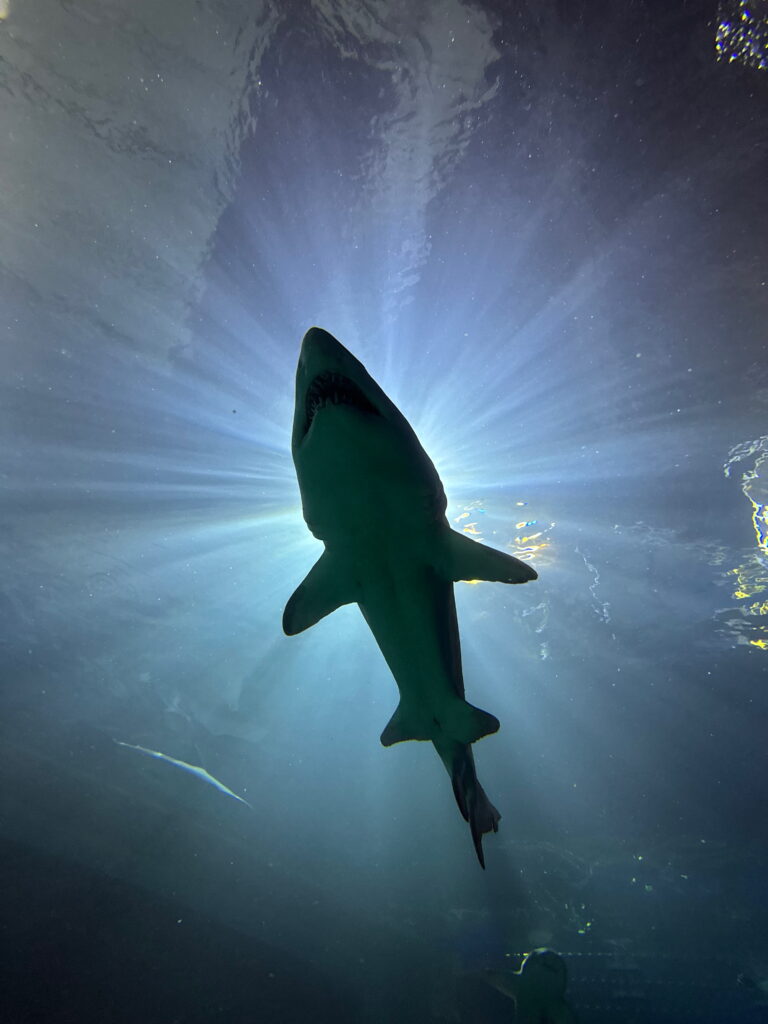

Greetings, travelers! Grab a towel, maybe a snorkel too. This week we’re returning to a destination you may recall from last year’s itinerary called Doom Shanty — the horrors of the underwater world. But as seasoned visitors on this second trip we’re focusing on a specific threat. This death from below is almost as old as natural threats get. It was swimming in the waters of our planet before the land had trees. I speak, of course, of the diverse group of apex predators we call sharks. On this 50th anniversary of Jaws, a movie which changed movie-going and some people’s views of the ocean forever, let’s look at the evolution of sharks as the thing we fear in movies in a segment called Maybe Shark (doo doo doo-doo doo-doo).

Sharks have been around for almost half a billion years. As reference Homo sapiens — modern humans — have been around a short 300,000 years. Sharks are really good at what they do, which is almost constantly eating, sometimes reproducing, and mostly not being killed by other hungry things in the ocean. This is why they are sometimes called nature’s perfect creatures. And yet, to call sharks’ evolution perfect is to presume some sort of direction towards perfection. This is a mistake, as evolution has no direction — it’s just a series of random genetic fuck-ups that sometimes yield cool new ways of not dying. Sharks have been remarkably successful in adapting to changing conditions — everything from competition for food to global extinction events.

And what accounts for this success? Let’s drop below the waves in this sturdy cage and have a closer look. Sharks are fish, but importantly — and weirdly — they are mostly boneless. Their body structure is kept relatively rigid by tissues made of cartilage (what human ears and nose tips are made of). Being boneless makes sharks more buoyant. Lucky for us, even this cartilage fossilizes to some degree which is how we know anything at all about the most ancient sharks. The skin of a shark is composed of thousands of tiny teeth-like structures called dermal denticles, which is why it feels like sandpaper. Put another way, sharks are literally covered nose to tail in teeth.

Sharks have phenomenal eyesight and an extraordinary sense of smell (they can detect odor molecules in dilutions as low as ten parts per billion). But sharks have a literal sixth sense too — they can detect electrical impulses in the water. Organs with the badass name of the Ampullae of Lorenzini form a network of mucus-filled pores that are both electroreceptors and magnetoreceptors. Why is this interesting? These ampullae are so sensitive that they can detect the electrical stimuli from the muscle contractions of potential prey. Too dark to see that tasty seal in the water column? No problem, sharks can feel their victims’ electrical presence. It’s almost magical. Having organic magnets is useful too. And this is why sharks can migrate ridiculously long routes around the planet without problem. The ampullae of Lorenzini are a built-in GPS system.

You’ve probably heard that sharks need to keep swimming or they will die. This is mostly true since, without lungs, it is the flow of oxygenated water through their gill plates that allows for respiration. But it isn’t completely true. Some bottom-dwellers, like angel and nurse sharks, have an extra organ than manually pulls water in over their gills so they can stay at rest for long periods of time. Which is why scuba divers will often encounter a shark just sitting there in a crevice. It’s momentarily alarming, sometimes terrifying, even if these species are completely harmless to humans.

So, yeah, sharks are adaptable. But it doesn’t end there. Have you heard of intrauterine cannibalism? Just what it says on the tin: shark sibling embryos that eat each other inside the uterus of their mother. (I must have missed the verse in the song Baby Shark on this.) How on earth is this a good thing? Turns out, sand tiger sharks only ever produce two pups — one from each uterus. This is far smaller than the normal litter of shark babies which for other species is at least a dozen. Baby sharks are small of course, which makes them prey, so the larger the litter size the better the chances some of them will survive. But with only two pups the sand tiger shark has the odds stacked against it. Unless the babies come out of the womb as seasoned killers already, that is! Not only do the cannibal embryos get a headstart learning the taste of blood from their unborn brothers and sisters, but statistically this is survival of the fittest — with only the best killers coming out into a world ready to climb up the predator chain quickly. There is video of intrauterine cannibalism. It is alien and disturbing and gross and completely awesome.

One note before we open this cage and soil our wetsuits. I mentioned above that one of the hallmarks of sharks’ longevity is that they are mostly not being killed by other hungry things in the ocean. They are certainly being killed by things on the ocean and that’s us, human beings. Mostly this is purely economic: humans kill 100 million sharks annually, mostly for the value of their fins, meat, skin, and liver oil. Many more are killed as bycatch when fishing for other things. But we’re also destroying their ecosystem as habitat is contaminated by toxic run-off, ripped to shreds by bottom trawling, or simply denuded of prey because ocean temperatures are rising past levels where fish can survive. More than a third of all shark species are facing extinction.

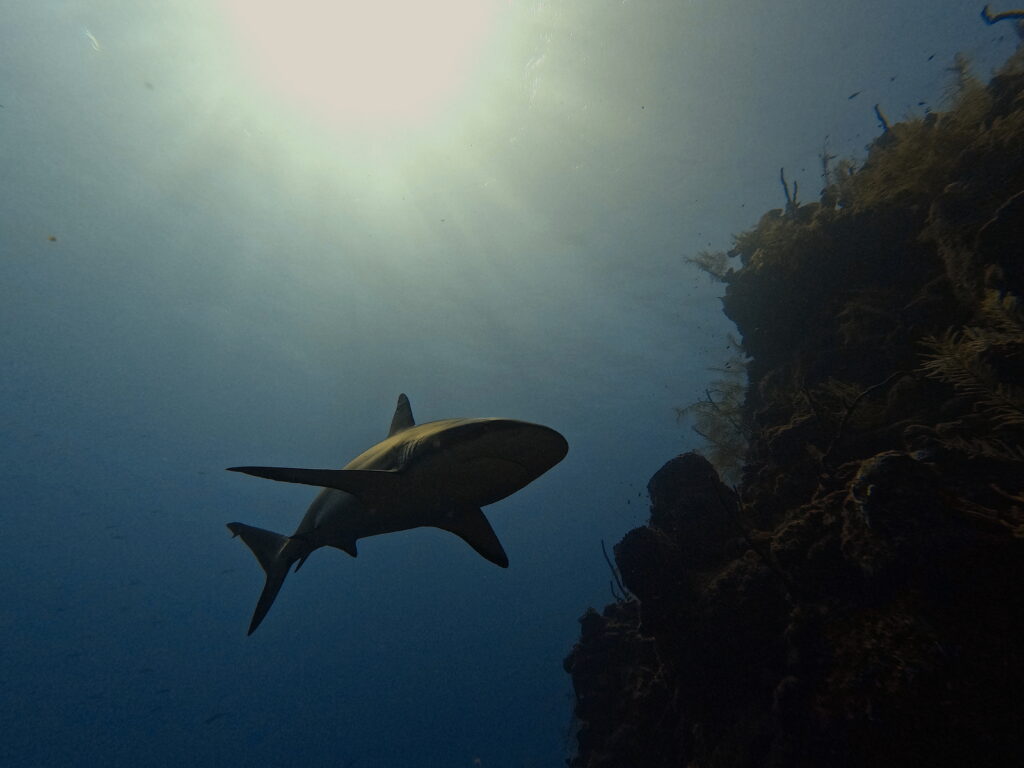

There’s another reason humans are a threat, though, and that has less to do with the actual killing of sharks and more with our attitudes towards them. The vilification of sharks is a full-blown industry, as the films we are about to discuss exemplify. With the exception of Pacific Islander cultures, the modern view of sharks has almost universally been one of fear and malevolence. We fear sharks thus we do not value them. This is a problem because an ocean without sharks is even scarier than an ocean with them. Without sharks, the global food web — a web that leads to your dinner plate and far beyond — would unravel. Entire ecosystems would collapse as prey species would overpopulate, herbivores would run amuck decimating coral reefs and seagrasses, making way for an explosion of algae all over everything. This would noticeably decrease oxygen production globally, making room for even more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, hastening global warming. And we all know how that’s going. So, yeah, sharks are scary, but we need them if we want this third rock from the sun to continue to be habitable at all.

OK, the cage is unlocked. Find your dive buddy and let’s swim out slow and orderly. We’re gonna explore the history of sharks in horror movies.

Holy mackerel there are a lot of films about sharks! Far too many to watch — or want to watch. Lotta chum in these waters. But there are some useful ways of separating The Shark Cinematic Universe into categories. First, shark films are a good case study for discussing the differences between thrillers and horror movies. Often these two genres intermix. Sometimes thrillers have horrific elements. The best horror keeps you on the edge of your seat like a good thriller. But they are not the same. Horror’s engine is fear. A thriller runs on suspense. And this is why there are so many shark films that are not horror. For the most part Jaws from 1975 is the line demarcating the shift from shark thrillers to shark horror. (More specifically, that precise transitional moment was probably when young Alex Kintner gets torn apart on his raft.)

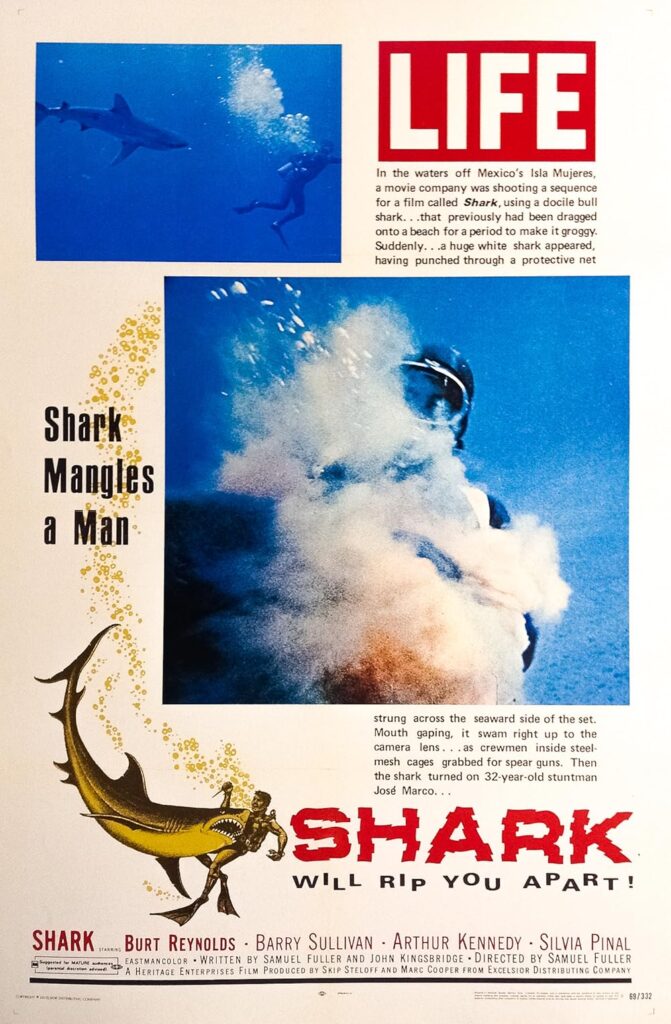

Pre-Jaws films with sharks were mostly adventure flicks. White Death (1936), filmed by Zane Grey as a fishing trip side-project, is basically a Western set on the ocean. The Sharkfighters (1956) is a fictionalized after-story of the sinking of the USS Indianapolis during WWII — the tale of shipwrecked sailors being ravaged en masse by sharks which you may recall that Quint famously recounts in Jaws. The Sharkfighters is notable for being one of the first films to use footage of real tiger sharks rather than puppets or dummies. Then there’s Shark (sometimes Shark!, 1969) starring Burt Reynolds and Silvia Pinal. Filmed in Mexico pretending to be Sudan it is mostly agreed that this film was an excuse for Reynolds and director Sam Fuller to party in beach towns. This movie has all the early tropes of ocean thrillers — unscrupulous treasure hunters, brave Westerners surrounded by caricatured locals, and the thought of sharks being in the water as all the tension needed. In a kind of snuff film-esque twist, it was claimed that a stunt diver was killed by a shark during filming. Life magazine did a photo spread of stills purportedly captured on film. After an investigation the magazine corrected itself, calling the story a hoax that involved a dead or drugged grey shark and “lots of ketchup”. But that didn’t stop the producers from marketing the film based on the supposed stuntman death. Maybe it was the success of this gruesome marketing that was the true harbinger of the turn towards horror just six years later.

Do we really need to talk about Jaws? Who has not seen this movie? OK fine, scaredy-pants. But who has not felt the cultural impact of this movie? No one. Usually listed as a thriller — and I can see this argument — it is undeniable that the result of Jaws was pure fear. To this day there are people of a certain generation who will not swim in the ocean because of this single movie. Only the second feature film of young director Steven Spielberg, Jaws was a notoriously difficult movie to make well — from the instability of filming at sea to the mechanical shark named Bruce to Robert Shaw battling alcoholism on-set. But made well it was, so well that it created an entire new category of movie, one whose lines of ticket-seekers wrapped around movie theater blocks, effectively “busting” them. The blockbuster became the new Hollywood business model: the pursuit of high box office returns from heavily-advertised action and adventure films released during the summer. For our purposes what Jaws proved is that there clearly was a market for being scared by sharks.

Sidenote: the main shark theme music — a could-not-be-simpler alternation of two notes one half-step apart — may be the most recognizable piece of music in the entire history of film. Composer John Williams described the theme as “grinding away at you, just as a shark would do, instinctual, relentless, unstoppable.”

You know what else is unstoppable? Film studios’ pursuit of money. After Jaws there was an absolute frenzy of shark movies looking to take a bite out of the market. Jaws itself had three sequels, the first of which was decent. The other two we shall not discuss. The 70s and 80s were awash with knock-off shark flicks: Mako: The Jaws of Death which was first on the bandwagon in 1976 and at least spices up the plot with a man who achieves some telepathic connection with sharks from a shaman’s medallion and Shark Kill, also from that year, which is just made-for-TV slop. Oh but then Mexico got in on the action releasing Tintorera (1977) — we’ll come back to this one, Cyclone (1978), and Bermuda: Cave of the Sharks (also in 1978).

Hang on, don’t forget the Italians, next in line (such as Italians know how to form a line — I can say this, as I am Italian). Spending exactly one month in theaters in 1981 before being sued into oblivion by Universal was Great White (also known as The Last Shark) starring Vic Morrow who would be decapitated by a helicopter stunt gone horribly wrong on the set of Twilight Zone: The Movie less than two years later. Courts would rule that Great White was exactly the same film as Jaws. Which may be, but I found it to be a great watch. None other than giallo maestro Lucio Fulci was a fan of the aforementioned Tintorera. He wasn’t a big enough fan to approve a zombie versus shark scene suggested by his producer for his film Zombi 2 (aka Zombie Flesh Eaters), but that didn’t stop it from being filmed by his special effects lead Giannetto De Rossi inside a large saltwater tank with a recently-fed and heavily-sedated shark. Eventually Fulci agreed to include the now-infamous (and ridiculous) sequence. But here’s the interesting part: a local Mexican diver and photographer named Ramón Bravo was hired to fill in for the stunt man as the underwater zombie fighting the actual shark. Ramón Bravo wrote the novel Tintorera upon which the movie was based! Full circle.

So that’s the immediate before and after Jaws. First, sharks as thriller plot sidepieces shot poorly without color correction (or using stock footage). Then Jaws. Then a whole bunch of not-great derivative films coming from the usual suspect countries. That’s only the beginning though. Things start getting really good again — or at the very least, more interesting — around the turn of the millennium. This is largely due to what I consider the second best shark horror film ever made, Deep Blue Sea. Directed by Renny Harlin and released in 1999 this film stars Thomas Jane, Saffron Burrows, Samuel L. Jackson, and LL Cool J. Which, c’mon, that’s one hell of a cast. The premise here is basically what if we made a killer shark movie more like a slasher film? You may be wondering, how would you even do that? First, genetically enhance your sharks in a secret research facility. Make ‘em smarter and more cunning. Then partially flood the facility so the sharks can move about its corridors, but humans can still run and move through the same corridors. Voila! Slasher shark film! You may think that there was nothing redeeming about James Cameron’s Titanic from 1997, but you would be wrong, as the sets for Deep Blue Sea were constructed atop the massive water tanks that had been built in Baja California for Titanic. Its heart — or at least its massive tanks — did go on. Deep Blue Sea is a fun film, a scary film, and a pretty novel one at that. The baddies here aren’t the sharks so much as the people who modified and experimented on them. Sharks as antagonist but not as villain; sharks as bullet but not the gun. This is a tonal shift we will see again. More than anything Deep Blue Sea jumpstarted shark films again, yielding a whole lotta awful — basically the second wave of sharksploitation — interspersed with some pearls.

It took about a decade to really get going, but honestly the sheer amount and at least conceptual creativity of the shark films about to be unleashed on the public is impressive. Let’s run down a few:

- In Sharktopus (2010) there’s only one reason the US Navy would engineer a half-shark, half-octopus creature for combat. It’s so that we could look back on the relative sanity of this hybrid once the sequels were released. Please enjoy Sharktopus vs. Whalewolf and Sharktopus vs. Pteracuda.

- The premise of Sharknado (2013) starts with a tornado that scoops up and throws ravenous sharks all over town. And that’s the least ridiculous of the premises of the five Sharknado films which, like all horror series that have run their course, eventually goes to outer space.

- Ghost Shark (2013) solves a problem with sharks, namely that you can only be attacked by one if you are in a large body of water. This movie is hilarious. The slightest amount of water, even just a puddle, can unleash Ghost Shark!

- Please read this movie title a few times: Sharkansas Women’s Prison Massacre (2015). This film delivers everything (except an enjoyable experience): a fracking mishap, giant prehistoric sharks, female prisoners on a work detail in a swamp, and Traci Lords playing a detective for some reason.

- As a fan of Christmas horror, I watched Santa Jaws (2018). My strong advice to you, travelers, is not to watch this. The gag of a Santa hat being worn atop a shark dorsal fin slicing through the water is mildly humorous precisely one time.

- Midwest represent! Sharks of the Corn (2021) is exactly what it sounds like — and should not be.

- Nothing stirs a sense of patriotism like Americans fighting unkillable sharks launched to the moon by the Soviets years ago. Please salute Shark Side of the Moon (2022).

As you can see from these films sharks have become bolt-on accoutrements to almost the entire range of horror tropes and sub-genres. Monster movies, ghost flicks, religious horror, space frights, and then just straight up replacement of killers from previous films with … sharks. Is this lazy? Sure. Is it fun? Usually! In 75 years sharks have gone from representing the threat of the unknown, to evil killers, to placeholders for whatever situation needs more menace. We said it before at the beginning of this journey, but it probably bears repeating: sharks have been around forever because they are almost infinitely adaptable.

Travelers, I know what you are thinking: there are so many shark horror films — and most of them are terrifically bad. Can’t you please provide a smaller map of the best destinations? Sure, can do.

Open Water (2003) — Based on the true story of two scuba divers left behind when their dive operator doesn’t perform a proper headcount, the horror here is more the terror of being alone in the sea. Only later do sharks do what sharks do best. As for what really happened to these divers we will never know. Maybe they died well before any sharks showed up. Maybe there were never any sharks at all. All we do know is that those divers did not live.

The Reef (2010) — Based super loosely on a true story where two people were killed by sharks, this film uses real sharks superbly edited to tell the tale of a group of folks trapped on a capsized yacht. A very similar premise to Open Water. The characters here just have the hull of a boat to cling to instead of bobbing around in the waves. The result is the same ultimately.

Bait (2012) — Australians know how to do sharks (as you might remember from the recent grotch Dangerous Animals). Bait takes place almost entirely inside a flooded grocery store next to a beach. If you liked the everyday confines of the movie The Mist and sharks in corridors like Deep Blue Sea you’ll love this.

The Shallows (2016) — Starring Blake Lively … and a shark. And that’s really it. What’s incredible about this film is how a single person trapped on a rock with a Great White shark circling around makes for a compelling film. But it very much does.

47 Meters Down (2017) — Stuck in a cage at the very limits of recreational diving (and nitrogen narcosis) this is The Shallows with one extra character and a giant twist at the end. Obviously there are sharks, but there’s also the overriding dread of an ever-diminishing air supply to quicken the pulse.

Under Paris (2024) — I found this more compelling than the Olympics opening ceremony it meant to prefigure (which also took place on the Seine). Under Paris is actually a really fun movie with flooded catacombs, mutant sharks, and a triathlon stand-in for the Olympics that becomes a chomping smorgasbord.

There are so many others. You could watch one shark horror film every week for a year and probably not run out. I do not advise doing this.

Let’s conclude this week’s journey with a quote from a recent New Yorker piece on what we really have to fear about sharks:

There is no such thing as shark-infested waters, in the same way that there is no such thing as a child-infested school. You cannot infest your own home. Fear is, of course, a great good. It can be a form of wisdom. But if we could reorient the sentiment—and direct it, for instance, toward those humans whose vested interests lie in persuading us to acquiesce in the living world’s destruction—we would fare better. Beware an ExxonMobil-infested State Department; beware a fossil-fuel-infested politics. These are dark times, and there are many things to fear. But none of them are found swimming under a vast sky as the waters around us warm and empty.

That’s it, my waterlogged travel-mates. You can surface now, but carefully. Stay vigilant out there, but I really wouldn’t worry about sharks. Until next time, I am your faithful tour guide.

A full list of the movies mentioned above can be found at Letterboxd. Find out where to watch there.

The Terror Tourist is my occasional segment on the Heavy Leather Horror Show, a weekly podcast about all things horror out of Salem, Massachusetts. These segments are also available as an email newsletter. Sign up here, if interested. The segment begins at 22:40 in this episode: