Networks and lines

Abstracted map of the Paris metro

I have been thinking about networks since Craig’s thought-provoking comment about the radial nature Chicago L system a few days ago. Thing is, I can’t shake the feeling that narrative and transportation networks are somehow related.

One easy relationship has to do with consumption. I enjoy being on the subway because it affords me time to read that I otherwise would not have. (I turn down rides home because I crave the time to read on the subway.) But what I really love is the way the L — especially when it is underground and impervious to cell transmission — eliminates options. You may be late for work, but there’s really nothing you can do about it. You can’t call anyone; you can’t get off the train and get to work any faster; you’re stuck. And that is wonderful. I feel like I suffer from a surfeit of options sometimes. It is so nice to just resign yourself to the moment. I’m going to keep reading until my stop, damnit. So nice to succumb to linearity.

But that’s not really what interests me. I’m still trying to tease this out, but clearly subway system design has conceptual similarities with new media. Stories can be point-to-point, multi-linear, radial, and true networks. They can even break out of the established route, creating new stations further afield. If you mapped these narrative arcs I bet they would bear a striking resemblance to the abstracted maps of subways around the world.

Was This Information Useful? Yes | No

Reading Microsoft’s primer for parents who want to decrypt their kids’s computer slang is like listening to über-caucasian Bill Kurtis announce that the murder suspect also “did drugs and was into [dramatic turn to address the camera] rough sex.” It is just so overwhelmingly unhip that you are compelled to keep staring at the screen.

Among the terms that Microsoft highlights to help you “protect” your children:

“warez” or “w4r3z“: Illegally copied software available for download.

“h4x“: Read as “hacks,” or what a computer hacker does.

“sploitz” (short for exploits): Vulnerabilities in computer software used by hackers.

“pwn“: A typo-deliberate version of own, a slang term that means to dominate. This could also be spelled “0\/\/n3d” or “pwn3d,” among other variations. Online video game bullies or “griefers” often use this term.

Thank you, Microsoft. Now I finally have the tools to protect my family. Actually, it is a clever ruse. Big Brother masquerading as Beaver Cleaver. Aw shucks, did I just get h4xxored?

Whose skills?

I am on the L tonight. The man next to me is reading a printed Powerpoint deck on his lap. Three points per page. No more than a few words per line. Like a set of flashcards or a very large type edition of a book. Except that the storyline has been broken down into bullets. I think maybe he is doing foreign language drills or something. It all looks very See Jane Run.

I peer closer. The subject matter is serious indeed. The deck is a school board report instructing teachers on how to raise the abysmally low reading skills of their K-3 students.

• I wince at the irony.

• I think of Tufte.

• I exit at the next station.

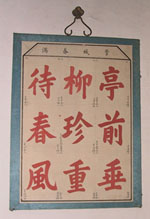

Physicalized words

I can’t read Chinese, though I am able to at least distinguish it from Korean and Japanese scripts. (Cut me some slack, that’s progress! But don’t even ask about distinguishing Traditional from Simplified. I’ll have to be content in my ignorance on that one.) What this means is that, since I have no idea what idea is being conveyed, my growing love for Chinese characters is almost purely visual. A reverse ekphrasis, the strokes of even the most mundane lines are painterly, evocative of an artform more fully engaged with the space around it than Western writing. Chinese calligraphy, such as I have seen it, is more akin to dance or yoga than it is to other scribal arts. It is all very physical.

Consider the “calendar” in the image above. Called the 81 Days of Winter, it is a single phrase that evolves slowly over the course of the winter. Each day the author/painter adds one stroke to the characters; a total of 81 comprise all nine characters. Ticking off the days like an Advent calendar, the phrase is complete by the end of winter:

The weeping willow of the pavillion waits for the warm breath of spring.

But it isn’t just script that is spatialized.

The item on the left is called a Ruyi. Long ago it was an imperial backscratcher, but it eventually lost that function altogether and merely became a royal symbol. The item to the right is a spitoon shaped like a persimmon flower. Together they form a visual pun. The word “ruyi” also means (or sounds like) “whatever you wish” in Chinese. The word for persimmon also means “everything”. So, taken together, the two completely symbolic objects mean “everything you wish for”. You see these objects conspicuously placed together on furniture throughout the Forbidden City, a portmanteau resting amongst the other objects of daily life.

The Good Earth

There’s a possibility of upcoming work in China, so I’m trying to get a feel for the history, places, and people. I had read some “Complete History of” titles for the macro sweep view when Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth was released in a new edition. (OK, fine. It was for Oprah’s Book Club. Can I help it that she picked this book too?) It is a deceptively simple book about a farmer who achieves great success through hard work and love for his land while, periperhal to his rural experience, the country heaves and lurches toward revolution. The tale is reminiscent in a way of William Dean Howells’ classic American novel The Rise of Silas Lapham, though Buck’s story is made more powerful by the knowledge of what would happen to China after she wrote the book in 1931. Indeed, the final scene somewhat eerily presages the widespread seizures of land that marked the civil war and Communist rule.

Anybody have any other good titles on Chinese life, history, or politics?

Wine and fine fabrics

Gutenberg, the story goes, was inspired to build his printing press from the mechanics of a wine press. Who knows if that’s true or not, but I’ve always loved the idea that the most important invention in the history of the world sprang from a way of making alcohol. No less interesting a story — though certainly better documented — is the degree to which the automated weaving loom created by Joseph-Marie Jacquard in 1802 inspired punch-card controlled computing and, arguably, the entire notion of separating data from the control program in an automated system.

I’ve got some history of fascination with the loom as a metaphor for computing and so I was naturally drawn to James Essinger’s new book on Jacquard and his loom. The book is about 100 pages too long and too strident in its claims about the importance of the loom to the history of computing overall, but it is not a bad book at all: controlling weaving patterns with punch-cards did in fact inspire Charles Babbage and Herman Hollerith to do the same with their computing and tabulating engines. What’s most interesting to me is the historical prevalance of the computing-as-weaving or computing-begat-from-weaving motif. Though Ada Lovelace was probably the most articulate in portraying the linkage, the idea has never been so much a part of the popular imagination as it is today in the World Wide Web. Arachne’d be proud.

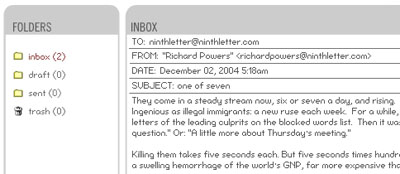

E-mailing Richard Powers

The e-lit blogs are abuzz about “They Come in a Steady Stream Now,” a new online piece by Richard Powers, the much-lauded author who consistently joins themes of technology and art in his novels. The general tenor of the comments on the new piece (with exceptions) seems to be mild disappointment that such an esteemed author didn’t create a masterpiece with his first foray in digital lit. I disagree, but not because “They Come in a Steady Stream Now” is exceptional — it isn’t, though it is very good indeed.

Thing is, Richard Powers is already an e-lit author. I saw Powers speak at the Chicago Humanities Festival a few years ago. It was the first time I’d heard him after years of knowing him through the written word alone. Perhaps that explains what happened to me. Powers delivered a reading of what came to be called “Literary Devices” at the CHF. This gets a bit convoluted so follow me here. In the listening “Literary Devices” seemed like a straightforward recounting of an e-mail exchange that Powers was involved in after delivering a real paper called “Being and Seeming” (“real” because I Googled it right after the talk — still online here). I was completely captivated by the conversation which, in a nutshell, revolves around a system called DIALOGOS, a next-generation ELIZA that convincingly writes fiction and sucks Powers into an ongoing exchange. It was only after the session ended on my way home did I realize that I had been completely duped. The CHF had not invited him to deliver a paper — it was total fiction, just sittin’-around-the-campfire storytellin’. And I had given myself to it utterly. I was the test subject who couldn’t distinguish the human from Turing’s machine.

Now, granted, this wasn’t electronic literature. Hell, it wasn’t printed literature. (Only much later did Salon publish the story, since removed, but available for purchase now.) This was oral literature in its most primitive form. Yet, in its colloquial, fast-paced, almost stream-of-consciousness delivery it really did evoke an e-mail exchange: call it performance e-lit. I was so amazed at how taken I was with this story I e-mailed Powers as soon as I got home. Like the now-fictional correspondent from the talk, I was the audience member who was striking up a real dialogue with the author, effectively continuining the narrative by e-mail — my own personal electronic appendix to the story.

All of this is an elliptical way of making the point that I consider the reading of “Literary Devices” to be Powers’ first jump into electronic literature, though it had none of the trappings of typical e-lit. No links, no point-and-click interactivity. But in its is-this-real-or-am-I-witnessing-artifice way it was the perfect Turing test and one that spawned at least one (though probably more) personalized narratives via other channels. The experience of the story, rather than the words on the page, was akin to some of the best e-lit experiences I’ve had and that’s why I consider “Literary Devices” an exemplar of the form.

“They Come in a Steady Stream Now” is certainly worth reading — Powers as always plumbs the human depths of technology — but it is more run-of-the-mill electronic literature and that, in the end, is why it is, well, run-of-the-mill.

UPDATE: Powers joins the conversation at Grandtextauto. An 8th e-mail, so to speak.

a + 30 + a’

I hadn’t read John McDaid since his seminal hypertext fiction Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse helped push me out of traditional literary studies onto the track I’m on now. Eight years ago maybe? Then this week Boing Boing enthusiasically blogged “Keyboard Practice, Consisting of an Aria with Diverse Variations for the Harpsichord with Two Manuals,” one of McDaid’s short stories. Since it caught me in that rare moment when I have just finished a book on the train to work and have nothing to read on the ride home and it was available for download I thought I’d give it a try. Well well well. I gotta agree with Cory. This is one hell of a story. You have to think McDaid is familiar with Richard Power’s Goldbug Variations (especially given his epigrammatic mention of gene sequences), the only other story I know so self-consciously influenced by Bach’s Goldberg Variations. I dare not try to wring a synoposis from either. Suffice to say that McDaid ably turns the reader into a rapt listener at a futuristic piano recital. It is a beautiful, lyrical story. Frankly I don’t remember his prose being so textured, but maybe that’s because I was too enamored of the medium back in the Uncle Buddy Hypercard days. In any event, this is worth your time. Pop Glenn Gould on too, if you have it. Download here.

Derrida departs

Upon returning to the States I learned that Jacques Derrida died in Paris on the day I left there. Reading Derrida was tough, no question about it. But you felt so damn accomplished when the concepts all came together. Adieu, monsieur.

Coincidentally, that’s Thoth, the ancient Egyptian god of writing (and source of the “Tut” in Tutankhamun), on the cover of Of Grammatology. Makes sense, I suppose. Aren’t most of Derrida’s ideas present in the Thoth episode of Plato’s Phaedrus?

Must. Stop. Making Egypt references.