No-go on TiVoToGo

Today TiVo announced the availability of TiVoToGo, a feature they first mentioned almost a year ago. TiVoToGo is supposed to allow you to copy recordings from your Tivo(s) to your local network for archiving and playback on your computer. Now, aside from the fact that MythTV and ReplayTV have been able to do this for some time, and ignoring the current unavailability of this feature for Mac, and setting aside the nasty DRM they’ve included, and temporarily accepting that the software that allows DVD’s to be created is neither part of the service fee nor even available yet, and trying not to focus on the annoying ability for a show to be desigated un-copyable by its owner, the fact is that TiVo isn’t ready for this rollout.

Sure, you can install the new desktop software, upgrade your MPEG2 codecs, get everything ready on your home network — but it still won’t work because TiVo has not rolled out the box-side software uprgade that enables the service! You can get on a “priority list” for the upgrade, but they are saying that could take weeks. There’s no surer way to piss off your best customers than to make available a product that doesn’t work yet. Why even release it? Why not roll out the set-top software upgrade first? I mean, why empower a user to download and configure their own system only to have to wait for more software that is out of the control of the user and, by the way, gives no easy notice that it has even been updated?

I’m annoyed.

Resolved

OK, I’ve given these a lot of thought. Here are the tasks I resolve to accomplish in 2005.

- Learn how to conjugate Italian verbs in a tense other than the present. This will help me formulate the sentence “Would you be interested in being my wife in an alternate reality?” when I finally meet Sylvia Poggioli, which, I suppose, is another resolution for this year.

- Get a goddamn backhand. I’m done performing acrobatics to be able to hit every ball as a forehand. Left-side muscles atrophying, I’m starting to look lopsided.

- Fall in love with NASA again. C’mon, people, seduce me. I’m easy.

- Be nice to political bloggers. That is, I resolve not be so condescending to the legions of “Olde Media Killers” whose contributions to the global dialogue mostly include copying scads of text from other sites and appending small comments like “Awesome” or “Devastating” or “Go read this”. Hint: you don’t need a site for this. It is a called an RSS Reader. (Crap, guess I need to resolve harder.)

- Learn to match beats when remixing. Currently my efforts sound like a session of “Michael Rowed the Boat Ashore” gone tragically askew.

- When home, watch only high-definition television programming. This might be difficult since I rarely watch live television (‘cept when the Cubs play) and my TiVo don’t do high-def. I must be strong-willed for this one.

- Convert all old mix tapes to MP3. Not a technical problem but a problem of data scarcity. Much of this music is obscure, unlabelled, and basically un-Googleable. Damnit, tune-recognizing search tool — where are you?

- Become able to change my son’s diaper with one hand. Not sure what I will do with the other hand, but this will surely be impressive to onlookers.

- Avoid LAX like the Black Death.

- Avoid the Black Death.

- Get to know my nephews better. It is one thing to be fatherly, quite another to actively participate in avuncular kookiness and crazy relative hijinks. I am looking forward to this one.

- Figure out how to make my own oak switches for the Russian Baths. Come on, it isn’t that bad. (Hmm, this’ll pair nicely with #11.)

That’ll do for now. Twelve resolutions, twelve months. Wish me luck.

“Is it over?”

Today we put in Mary Poppins for the first time for our three-year-old son. He immediately asked if it was over. You see, Mary Poppins, like most movies of its period, opens with screen after screen of detailed credits. Today’s movies having barely any at all my son naturally figured the movie had ended. I mean, come on, that much text belongs at the end, right?

Two degrees of separation

Each year I give away a CD’s worth of music to my friends at the end of the year. Not so much a compilation of the year’s best, it is merely a collection of the music I enjoyed this year regardless of when it was released. Since I give it away at a party the tracks are largely uptempo. This year I tried my hand at mixing the whole shebang into one continuous track using Traktor, a simple program of shocking complexity. I wasn’t completely successful, but the experience did add one more bullet item to my growing list of resolutions for 2005: learn to match beats so as not to create music that sounds like an EKG pinging cardiac arrhythmia. (Full list of resolutions coming soon.)

My pal Len Perez also released a mix for his friends this year — four CD’s to my one — so I thought it interesting to note the overlaps. Granted our tastes are similar, but this very small scale collaborative filtering is still notable given that we receive our musical inputs from different sources.

So, the overlap: Orbital, Sasha, Mr. Projectile. Orbital released their last album this year; Sasha his first (studio album, that is). Mr. Projectile is the one to watch — perhaps the most promising artist of his genre this year.

Wine and fine fabrics

Gutenberg, the story goes, was inspired to build his printing press from the mechanics of a wine press. Who knows if that’s true or not, but I’ve always loved the idea that the most important invention in the history of the world sprang from a way of making alcohol. No less interesting a story — though certainly better documented — is the degree to which the automated weaving loom created by Joseph-Marie Jacquard in 1802 inspired punch-card controlled computing and, arguably, the entire notion of separating data from the control program in an automated system.

I’ve got some history of fascination with the loom as a metaphor for computing and so I was naturally drawn to James Essinger’s new book on Jacquard and his loom. The book is about 100 pages too long and too strident in its claims about the importance of the loom to the history of computing overall, but it is not a bad book at all: controlling weaving patterns with punch-cards did in fact inspire Charles Babbage and Herman Hollerith to do the same with their computing and tabulating engines. What’s most interesting to me is the historical prevalance of the computing-as-weaving or computing-begat-from-weaving motif. Though Ada Lovelace was probably the most articulate in portraying the linkage, the idea has never been so much a part of the popular imagination as it is today in the World Wide Web. Arachne’d be proud.

Carbone Dolce

Here’s an easy way to remind the kids that they’ve been bad this year without scarring them for life. There’s a super-simple, traditional Italian dessert called Carbone Dolce, literally “sweet coal”, presumably a confectionary joke, but possibly pre-dating the whole stockings for bad kids thing. In any event, it could not be easier. You melt 400 grams of chocolate then mix in about half that in crushed Rice Crispies, form into coal-like clumps, and let cool. Voila! All the recipes I’ve come across are in Italian and I know they call for white chocolate, but I cannot figure out how or why you’d make something look like coal with white chocolate. Any ideas? Anyway, add a few pretzel sticks to the mix and you’ve got yer sticks and coal for the holidays. Better than pre-packaged, I’ll say.

Merry Christmas, dear readers!

Here’s the crew of Apollo 8 sending a Christmas Eve wish (Quicktime) to Earth as they orbited the moon, the first humans to do so, 36 years ago.

Going, going, gone

The blogosphere likes to talk about toppling old media. Today, I saw it topple for real, with nary a blogger in sight. Beats my normal daydream-fodder cubicle vista.

I should have one hell of a view carved out for me when I return to work after the holidays. A temporary thanks to The Donald.

(Photo gallery here.)

Mommy, is that a type of swimsuit?

No doubt conservatives hear the gallop of the Four Horsemen in this story, but I find this totally hilarious. Someone at the YMCA near me needs a better Dayplanner. Citing “a very regrettable scheduling error,” the Y overlapped an all-night transgender fashion show with a 7am kids swim meet.

Tired omnisexuals. Protective yuppie parents without their lattes. Bewildered children. Hilarity ensues.

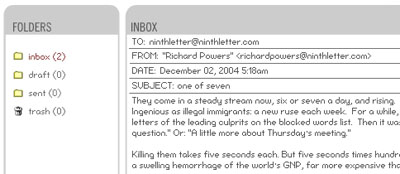

E-mailing Richard Powers

The e-lit blogs are abuzz about “They Come in a Steady Stream Now,” a new online piece by Richard Powers, the much-lauded author who consistently joins themes of technology and art in his novels. The general tenor of the comments on the new piece (with exceptions) seems to be mild disappointment that such an esteemed author didn’t create a masterpiece with his first foray in digital lit. I disagree, but not because “They Come in a Steady Stream Now” is exceptional — it isn’t, though it is very good indeed.

Thing is, Richard Powers is already an e-lit author. I saw Powers speak at the Chicago Humanities Festival a few years ago. It was the first time I’d heard him after years of knowing him through the written word alone. Perhaps that explains what happened to me. Powers delivered a reading of what came to be called “Literary Devices” at the CHF. This gets a bit convoluted so follow me here. In the listening “Literary Devices” seemed like a straightforward recounting of an e-mail exchange that Powers was involved in after delivering a real paper called “Being and Seeming” (“real” because I Googled it right after the talk — still online here). I was completely captivated by the conversation which, in a nutshell, revolves around a system called DIALOGOS, a next-generation ELIZA that convincingly writes fiction and sucks Powers into an ongoing exchange. It was only after the session ended on my way home did I realize that I had been completely duped. The CHF had not invited him to deliver a paper — it was total fiction, just sittin’-around-the-campfire storytellin’. And I had given myself to it utterly. I was the test subject who couldn’t distinguish the human from Turing’s machine.

Now, granted, this wasn’t electronic literature. Hell, it wasn’t printed literature. (Only much later did Salon publish the story, since removed, but available for purchase now.) This was oral literature in its most primitive form. Yet, in its colloquial, fast-paced, almost stream-of-consciousness delivery it really did evoke an e-mail exchange: call it performance e-lit. I was so amazed at how taken I was with this story I e-mailed Powers as soon as I got home. Like the now-fictional correspondent from the talk, I was the audience member who was striking up a real dialogue with the author, effectively continuining the narrative by e-mail — my own personal electronic appendix to the story.

All of this is an elliptical way of making the point that I consider the reading of “Literary Devices” to be Powers’ first jump into electronic literature, though it had none of the trappings of typical e-lit. No links, no point-and-click interactivity. But in its is-this-real-or-am-I-witnessing-artifice way it was the perfect Turing test and one that spawned at least one (though probably more) personalized narratives via other channels. The experience of the story, rather than the words on the page, was akin to some of the best e-lit experiences I’ve had and that’s why I consider “Literary Devices” an exemplar of the form.

“They Come in a Steady Stream Now” is certainly worth reading — Powers as always plumbs the human depths of technology — but it is more run-of-the-mill electronic literature and that, in the end, is why it is, well, run-of-the-mill.

UPDATE: Powers joins the conversation at Grandtextauto. An 8th e-mail, so to speak.

Accessing a book like a hard drive

If there’s a book that I remember more vividly than most from my childhood it has to be Inherit the Stars by James P. Hogan. The story is kicked off by the discovery of a 50,000 year-old human skeleton in a spacesuit on the moon. The ancient astronaut also had some effects with him, including a book. The scientists use a scanner that can read the book without opening its very brittle, damaged pages, basically peering into and reconstructing the sheets at variable depths. I always thought that was so cool.

Turns out this is no longer a fictional technology. Researchers at the University of Kentucky have figured out how to do it. Imagine being able to scan like this on a bookshelf- or library-wide scale, gulping down petabytes of data without cracking into the books themselves. (Via MGK. Thanks Matt!)