On Leaving IBM

Today, May 12, is my last working day with IBM, my employer for the last 13 years. It’s tough to adequately express how many opportunities IBM has afforded me and how difficult it was to make the decision to depart.

What follows is my shot at the first. I’ll let you guess at the second. (Hint: If you’re looking for a juicy exposé or vindictive exit letter, this ain’t it.)

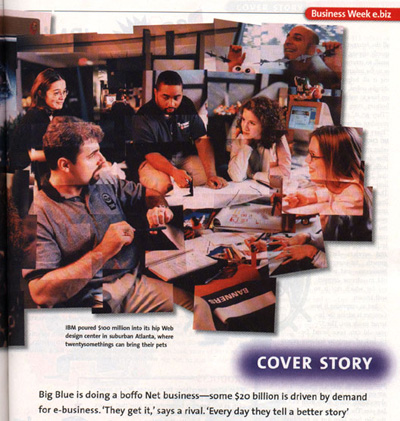

1998, Georgia Tech: I was finishing up a masters degree that didn’t exist three years prior. The tech bubble had not burst and everyone in the circles I moved in was decamping for the world of stock options, foosball tables, and the promise of becoming the next Netscape.

I had two offers on the table, one from a classic dotcom agency, and one fromIBM, a classic old person company. I struggled mightily with the decision and frankly I still don’t know exactly why I chose IBM. Might have been the I in the acronym — the suggestion of a career spent globetrotting and doing business in different cultures. But I do know that the other company ceased to exist only a few years later.

IBM then was a resurgent corporation back from the brink of death. Atlanta was the home to its Interactive Media organization, a kind of skunkworks dotcom agency — which I joined as a producer. (We had so few models internally for the web work we were doing that we borrowed titles from flim: producer, executive producer, even continuity director.) It was frenetic, design-oriented, and full of lots of people who very definitely were not old. (And neither was I. Dig the hair!)

I lucked into the part of Interactive Media that was building systems for live event coverage of the sports properties that IBM sponsored, primarily pro tennis, golf, and the Olympics. This was the world before cacheing and the cloud and so a certain amount of terror accompanied the task of running websites that could handle the load of sports fans worldwide checking scores covertly from work.

We were “webcasting,” crammed into windowless rooms or awful rented trailers, but let’s face it, I was onsite at Wimbledon, the US Open, and the Ryder Cup. And loving it. The stories and friendships from those days are some of the most cherished of my career. (Someday ask me about a sopping-wet Brooke Shields hiding out in our nerd bunker during a rain delay at Flushing Meadows.)

The moment that established the trajectory that would basically define my career at IBM — diving way deep, obsessively even, into the subject matter surrounding my projects — arrived with the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. I had been tagged by colleagues as “the guy who likes books” given my undergraduate pursuits, so I suppose it is not surprising that I would be given the lead on a cultural project. It was a massive undertaking, digitizing thousands of works of art, presenting it on a still-nascent web, and working across cultural and linguistic differences. It was, in short, a template for much of the work to follow.

With one interlude. In 2000 I somehow finagled my way onto the cruise shipIBM had rented as living quarters for its guests to the Sydney Olympics. A pal and I provided tech support in the computer lab for IBM customers to check e-mail and download digital photos. (It was the era before ubiquitous laptops and connectivity, you see.) It was also, perhaps, the greatest gig of all time.

Over the course of the next many years I had the privilege of leading a number of increasingly complex projects in cultural heritage. Eternal Egyptapplied the concept of an online museum to an entire country, across multiple institutions, and nearly all historical eras. Add in mobile phone and PDAaccess (hey, it was 2003!) and a History Channel documentary and you had the making of something great.

Moving away from material culture and into the realm of society and history, I was honored to lead the team that built the website for the newest Smithsonian museum, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, something not set to open on the mall for several years. TheNMAAHC Memory Book was one of the first citizen-curated content projects for the Smithsonian and is a great foundation for the museum’s bottom-up presentation of the African-American experience.

More directly in the lineage of the Hermitage and Eternal Egypt, The Forbidden City: Beyond Space and Time took IBM’s cultural heritage work away from the web and into multi-user 3D space. Modeling the square kilometer of the Ming-Qing era complex was my first taste of city design and crafting spatial interactions, a foreshadowing of relatively great import.

Interspersed among the cultural work were a few important projects that were both responses to world events. The Katrina disaster mobilized a crack team in IBM to develop Jobs4Recovery, a site that aggregated and geo-located employment opportunity in the states hit by the hurricane. This was particularly meaningful to me as my wife’s family was directly, sadly affectedby the disaster and its aftermath.

Working in Egypt before and after the 9/11 attacks gave me a perspective (and friendships) for which I am eternally grateful. So it was a real pleasure to work on Meedan, a news aggregrator/social network for current events in the Middle East and North Africa. Working with the non-profit of the same name, Meedan was built to use IBM machine translation and human volunteer editors and curators to provide English and Arabic translations of news stories and comments. I had worked much of my career presenting the treasures of the world’s material culture to broader audiences; Meedan was my opportunity to widen the definition of culture that we were hoping to bridge to others.

Perhaps the most transformative moment of my career came upon being accepted to the fledgling Corporate Service Corps, IBM’s internal “peace corps”, a hybrid leadership development and philanthropic program that sent small teams of IBM’ers to areas of the world that IBM does not currently do business. I joined the first team to West Africa and was thrilled to head to Kumasi, Ghana with nine other IBM’ers from around the world. We worked with small businesses to help them on all manner of problems. Being jolted out of a comfortable office setting to find common ground with colleagues from different lines of business and other countries was amazing enough, but I had the great fortune of our former nanny in Chicago, a native of Kumasi, returning to her family there and ensuring that I not only worked in Ghana but felt a part of the community there. It changed my life.

I got my first dose of what would become a full-on obsession in modeling complex systems for better decision-making when I inherited Rivers for Tomorrow from a retiring colleague. Rivers, a partnership with The Nature Conservancy, permits users to simulate different land use scenarios in river watersheds to see what the effects are downstream, so to speak, on water quality. It was a fun set of systems to model, but much hairier problems came shortly.

The project that I end on, whose roots I trace to the Forbidden City project, isCity Forward. I consider it a kind of simulator of cities using data in the same way that the Virtual Forbidden City was one in 3D graphics. You can read all about the project — heaven knows I have talked about it enough here and elsewhere, but the key thing is the world of urbanism that it opened to me. City Forward set me on a path to relationships with people making real change in cities around the world and showed me the promise of technology embedded in the everyday lives of city-dwellers. It is, in a word, the springboard that has launched me into my new role.

I realize that’s a pretty me-focused list of experiences and I will admit that this blog post is as much a personal retrospective as anything else. But I think it does a good job of making it clear how important IBM has been to my professional development, personal growth, and intellectual satisfaction. I could not have asked for a more fulfilling past 13 years and I leave with nothing but respect and thanks for what the company has done for my family and me.

And yet the list above glaringly lacks the most important thing that I am leaving. My colleagues in IBM have, to the person, been the most meaningful aspect of my career. To list everyone who made me a smarter person, a better colleague, a more understanding manager, a more collaborative partner, or better world citizen would take several blog posts, but suffice to say that I met some of my very best friends, a few mentors, and even a few professional idols in my time with IBM. My gratitude for my colleagues at IBM exceeds my capacity to express. Thank you.

So what now? I am off to the role of Chief Technology Officer for the City of Chicago under our new mayor, Rahm Emanuel. That’s a post for another time, but it’s fair to say now that it was an offer I could not pass up. I have been preaching smarter cities for a very long time; to let an opportunity go by to take real action in the city I love most would have filled me with regret. It is time to put my money where my mouth is.

IBM turns 100 years old this summer — a fairly amazing accomplishment for any company, let alone an IT company. I’m proud of what IBM has achieved, but even more proud of the people who have done the work. I’ll leave you with this extraordinary video, the best portrait of the people of IBM that I know. And the very essence of what I will miss most.

Upcomings

Spring’s nowhere near Chicago right now, but the seasonal onslaught of conferences seems not to heed nature’s cycles. I’m going to be in a bunch of places coming up. Would love to meet up if you will be near.

Transportation Camp East

New York, NY

March 5-6

South by Southwest Interactive (+ new day after Technology Summit)

“Smarter Cities: Driving Sustainable Growth”

Austin, TX

March 12 – 16

APA National Planning Conference

“Technology Infrastructure and Planning”

Boston, MA

April 11-12

RPA Regional Assembly

“Smart Cities, Smart Citizens”

New York, NY

April 15

National Mayor’s Summit on City Design

“Design and 21st Century Challenges”

Chicago, IL

April 27-29

Urban Systems Symposium

“Defining Urban Systems”

New York, NY

May 11-12

Full travel schedule here, for those interested. (There’s a good chance I will be in DC a bunch too.)

What it’s like to match wits with a supercomputer

I spent most of the May 1997 rematch between chess world champion Garry Kasparov and IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer sitting in a grad school classroom. I think it was Intro to Human-Computer Interaction, ironically enough. The professor projected a clunky Java-powered chess board “webcast” (the term was new, as was the web) so we could follow the match. The pace of chess being deliberative and glacial, it really wasn’t a distraction. Not to mention that, at the time, I didn’t know how to play chess. But I do remember people caring deeply about the outcome. I went to work for IBM the following year.

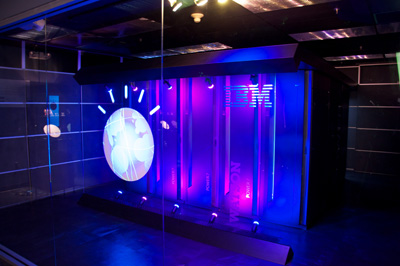

Deep Blue’s descendant, if not in code or microchips then in the style of its coming-out party, is Watson, a massively parallel assemblage of Power 7 processors and natural language-parsing algorithms. Watson, if you’re not a geek or a game show enthusiast, was the computer that played Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter on Jeopardy Feb. 14-16 of this year. Watson won.

Wednesday of last week I got a chance to play Watson on the Jeopardy set built at our research facility for the show. I did not win.

But I did hold the lead for a time and, in fact, I beat Watson during an unrecorded practice round. Honest!

Jeffrey Plaut of Global Strategy and I were the two human competitors selected to go up against Watson in a demonstration match. We did so at the culmination of a few hours of discussion with leaders from the humanitarian sector on how to expand Watson’s repertoire to put it to work in areas that matter. (More on that in a bit.)

IBM built a complete Jeopardy set for the actual televised match. Sony has lots of experience with this, as Jeopardy often goes on the road. But it’s clearly a hack: TV made the set look a lot bigger that it really is and the show’s producers had to jump through hoops to provide dressing room space and keep the contestants segregated from interacting with IBM’ers (to avoid claims of collusion, I suppose). Ken Jennings has some typically humorous insight on this.

Trebek was long gone, so we had the project manager for Watson host the session I competed in. He’s actually very good, as Watson went through a year of training with past winners and stand-in hosts. I was to play one round of Jeopardy. The rules were the same as the real game and Watson was at full computing capacity, with two exceptions. We were told that we could ring in and then appeal to the audience for help and, most importantly, Watson’s ring-in time was slowed down by a quarter second. The first I took as an insult — if I was going to compete against a computer I was going to do it myself — the second was a blessing.

Standing at the podium is certainly nerve-wracking. There’s a small screen and light pen for scrawling your name and then the buzzer. I stood in Jennings’ spot and it was striking to see how worn the paint was on the buzzer. From sweat? Who knows, but that thing looked like it had been squeezed to death. Contestants can see the clue board and the host, of course, but there’s also a blue bar of light underneath the clues which is triggered manually by a producer once the host finishes reading the last syllable of the clue. This is the most important moment, as ringing in before the blue bar appears locks you out temporarily. Watson had to wait a quarter second at this point and I am convinced it is the only reason we humans were able to get an answer in edgewise.

In a way, this moment is as much human-versus-human as anything. You’re trying to predict exactly when the producer will trigger the go light. Factor in some electrical delay for the plunger and it can be a real crapshoot. This is why past champions perfect their buzzer technique and ring in no matter what. They just assume they will know the answer and be able to retrieve it in the three seconds they are given.

I got a bit of a roll in the category called “Saints Be Praised”. My Catholic upbringing, study in Rome, and fascination with weird forms of martyrhood finally paid dividends. (I also learned after the match that my human competitor was Jewish and largely clueless about the category.) The video above shows me answering a question correctly — something that seems to have shocked my colleagues and the audience. (And I would have disgraced every facet of personal heritage had I messed up a question about an Italian Catholic from Chicago.)

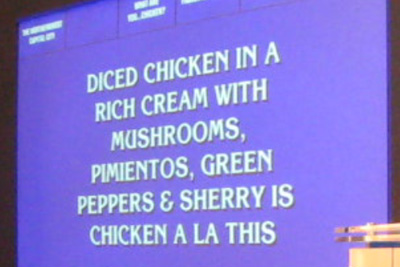

This clue was more interesting as Watson and I both got it wrong. The category was “What are you … chicken?” about chicken-based foods. Maybe my brain was still in Italian mode as I incorrectly responded “Marsala”, but Watson’s answer — “What is sauce?” — was way wrong, categorically so. This is insightful. For one, the answer, “What is Chicken A La King,” if Watson had come across it at all, was likely confusing since “king” can have so many other contexts in natural language. But Watson was confident enough to ring in anyway and its answer was basically a description of what makes Chicken A La King different from regular chicken. Note that the word “sauce” does not exist in the clue. Watson was finishing the sentence.

What’s most important and too-infrequently mentioned is that Watson is not connected to the Internet. And even if it were, because of the puns, word play, and often contorted syntax of Jeopardy clues, Google wouldn’t be very useful anyway. Try searching on the clue above and you’ll get one hit — and that only because we were apparently playing a category that had already been played and logged online by Jeopardy fans. The actual match questions during the Jennings-Rutter match were brand new. The Internet is no lifeline for questions posed in natural language.

At one point I had less than zero (I blew a Daily Double) while Jeff got on a roll asking the audience for help. And the audience was nearly always right. Call it human parallel processing. But if I was going to go down in flames to a computer I was damn sure not going to lose to another bag of carbon and water. I did squeak out a victory with a small “v” — and Watson was even gracious about it.

Thinking back it is interesting to note that nearly all my correct answers were from things I had learned through experience, not book-ingested facts. I would not have known the components of Chicken Tetrazini did I not love to eat it. I would probably not know Mother Cabrini if I didn’t take the L past the Cabrini-Green housing project every day on the way to work. This is the biggest difference between human intelligence and Watson, it seems to me. Watson does learn and make connections between concepts — and this is clearly what makes it so unique — but it does not learn in an embodied way. That is, it does not experience anything. It has no capacity for a fact to be strongly imprinted on it because of physical sensation, or habit, or happenstance — all major factors in human act of learning.

In Watson’s most-discussed screw-up on the actual show, where it answered “Toronto” when given two clues about Chicago’s airports, there’s IBM’s very valid explanation (weak category indicator, cities in the US called Toronto, difficult phrasing), but it was also noted that Watson has never been stuck at O’Hare, as virtually every air traveler has. (The UK-born author of this piece has actually be stranded for so long that he wandered around the airport and learned that it was named for the WWII aviator Butch O’Hare.) Which isn’t to say that a computer could never achieve embodied knowledge, but that’s not where we are now.

But all of it was just icing on the cake. The audience was not there to see me make a fool of myself (though perhaps a few co-workers were). We were there to discuss the practical, socially-relevant applications of Watson’s natural-language processing in fields directly benefiting humanity.

Healthcare is a primary focus. It isn’t a huge leap to see a patient’s own description of what ails him or her as the (vague, weakly-indicating) clue in Jeopardy. Run the matching algorithm against the huge corpus of medical literature and you have a diagnostic aid. This is especially useful in that Watson could provide the physician its confidence level and the logical chain of “evidence” that it used to arrive at the possible diagnoses. Work to create a “Doctor” Watson is well underway.

As interesting to my colleagues and I are applications of Watson to social services, education, and city management. Imagine setting Watson to work on the huge database of past 311 service call requests. We could potentially move beyond interesting visualizations and correlations to more efficient ways to deploy resources. This isn’t about replacing call centers but about enabling them to view 311 requests — a kind of massive, hyperlocal index of what a city cares about — as an interconnected system of causes and effects. And that’s merely the application most interesting to me. There are dozens of areas to apply Watson, immediately.

The cover story of The Atlantic this month, Mind vs. Machine, is all about humanity’s half-century attempt to create a computer that would pass the Turing Test — which would, in other words, be able to pass itself off as a human, convincingly. (We’re not there yet, though we’ve come tantalizingly close.) Watson does not pass the Turing test, for all sorts of reasons, but the truth is that what we’ve learned from it — what I learned personally in a single round of Jeopardy — is that the closer we get to creating human-like intelligence in a machine, the more finely-nuanced our understanding of our own cognitive faculties becomes. The last mile to true AI will be the most difficult, primarily because we’re simultaneously trying to crack a technical problem and figure out what, in the end, makes human intelligence human.

All good things.

It’s been two months now since we wrapped it all up. Could be that my lateness in writing about it was just to make sure that we really did mean that it was over. Or maybe I didn’t want to think about it being over. Most likely, it was sheer exhaustion and a house that needed putting back together.

In any event, certain parts of our final holiday party do need to be told. Sweet damnation, it was an amazing way to go out.

I’ve detailed the evolution of this particular fête previously, so I’ll just lay out the specifics. On December 11 my wife and I hosted the last event, completing an unintended triad of “world”-based themes that began two years ago with Around the World, continued last year with Out of This World, and culminated in this event, decisively, as The End of the World.

Newsflash: apocalypse isn’t the classiest theme for what is essentially a Christmas party. New Years Eve sorta has that tipsy tinge of impending end, but it’s never really the end, just a marker. (Except when the millennium flips, of course, and full-on pandemonium is acceptable.) We toyed with “at world’s end” as a physical location, ala Shel Silverstein’s sidewalk or cartographical terra incognita. But neither of these worked as well as the pure mayhem of doomsday.

Eschatology, it turns out, is a wonderfully flexible concept, so we went with it. Mad Max meets the Four Horsemen by way of Al Gore. With lasers and martinis.

The favor was a special challenge. The party takeaway has traditionally been some form of music-delivery medium and, though I have long since stopped considering compact discs adequate to this task, the truth is that they did lend themselves astonishingly well to what we came up with. See, it’s a clock. Tick tock, tick tock, time’s up. Get it?

We figured most people wouldn’t make the connection to the doomsday clock, though there is something wonderfully creepy about a bunch of clocks ticking out of time with one another (cf., Orbital’s “The Box” remix, part of the audio excerpt below).

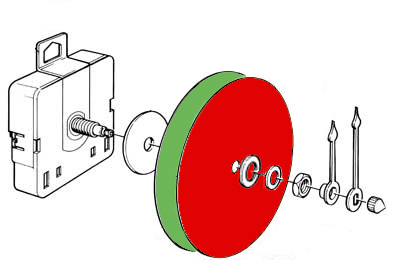

The clock face was composed of two CD’s — Doomsday and Rebirth — which were smooshed together and bolted onto the clock axle, as below. To listen to the discs you had to dismantle the clock, which consisted of unscrewing a single nut.

The clock sat in small frame which itself rested on a small “time capsule” that contained a scroll with holiday wishes and a reminder not to come back next year.

The last piece, really the only thing having to do with rebirth, was a small (live) spruce sapling hooked to the back of the clock rig. It all looked rather nice, festive even, though it was awfully time-consuming to assemble and frightfully delicate. I’d love to know how many clocks made it in working shape back to partygoers’ homes at the end of the night.

At the end of the world we will eat pork, a sign declared. We’re still not sure what that means, but the porktacular was a hit. With a nod to our stockyards, I’ll note that we used everything but the oink. Faves included the Bacon Waffles with Spicy Chicken and Maple Cream and the Red Velvet Cake Ball Meteoroids. (Here’s the full spread.)

Fingers the One-Handed Bartender returned this year and was responsible for much mirth, day-after illness, and possibly one pregnancy. We had intended to enlarge his veal pen of a bar area but never got around to it. We did however rig a display above his head that gave details on the custom drink menu. And the DJ booth had a special trigger for thirst, below.

Possibly my favorite new addition to the party was the DJ outfits. Last year we donned jackets festooned with electroluminescent wire, a tough thing to upstage — but in the intervening year the iPad had been released. And of course it wasn’t difficult to find shirts custom-reinforced to accommodate an iPad slid right into it. It was great fun. We had disaster video, spectrum analyzers, music-appropriate imagery, and all manner of screensavery stuff.

But the most fun was a LED ticker-tape app that allowed tweeting directly to it so that the crowd could scroll their own messages right across our chests. (Pretty sure that snippet below is “And the DJ is doing a great job” a brief interlude between what-a-bunch-of-nerds themed tweets.) The account’s still live, by the way. Maybe you’ll catch me wearing the iPad at work?

Other new additions this year included a drink shelf below the perishable electronics in the DJ booth. Call it a lesson learned from last year. The mirrored tree cones, staple of most past parties, also got custom spinners to throw disco ball shards of light around the room to remind everyone that they were, in fact, in a post-apocalyptic hell. And the popular photo booth had all manner of goodbye-cruel-world props.

Custom posters inspired by Britain’s wonderful WWII anti-panic propaganda decorated the house. (If you have not tried the Keep Calm and Carry On Calm-O-Matic, you really should.)

Lastly in the new things category, we went low-tech with a “memory board” for people to scrawl their thoughts about the last decade of bashes. It remained remarkably free of crude comments for much (but not all) of the night.

And yet it is the music and dancing that defines and prolongs this party. We didn’t have much luck recording the full set of Jesse Kriss, Michael Tolva and I this year, but this self-contained set does exist.

Conveniently, lots of people were singing about armageddon in the 1980’s. Thanks, Strategic Defense Initiative!

The EL jackets returned, of course, made seemingly all the fresher by the release one week later of Tron: Legacy. Way fun, way photogenic, and way too goddamn hot.

This year our visuals maestro Tom Herlihy did not have a calendar conflict with Kabul, Afghanistan and so was able to man the lights and projectors during about an hour of sobriety. Tom’s ever-able understudy Chris Gansen also lit it up, so to speak. For once in a club setting the air raid siren made sense.

The liquor globes made a comeback as well. Luckily Malört, Chicago’s very own rotgut, neatly tied together our love of the Windy City and beverages that pretty much ensure that your world is coming to an end.

Which is a nice seque to illness. You could say that we were on-theme with pestilence, but the sad truth is that it seems our home — usually infested with the virus that is small children — was coated with a fine film of some mutant strain of stomach flu. Several got ill, including my mother-in-law who spent the entire party in the dual perditions of non-stop barfing and having to listen to four-on-the-floor bass until 4 AM.

The other casualty was Jesse Kriss, the DJ savant and ringmaster of the music-making that has jolted the past few years’ parties. Yet, Jesse played for at least 90 minutes, ashen-faced but not so lethargic that he couldn’t whip the crossfader. It was magic to watch, until he too collapsed into a bed upstairs and merely felt the party through the house frame vibrations. I think Joey and I did a pretty good job keeping the music interesting, but it simply was not the same without Jesse as mixmaster of ceremonies.

Some people didn’t believe that this was the end, but many knew. You could tell from the thoughtfulness of the hostess gifts, such as the handmade party logo ornament above and the retrospective photobook.

Right, so. No need to dwell on it. It was a great run. I’ll sum it all up with the text from the note we included in the time capsule. (Mind the sap. It’s sticky.)

Who the heck throws a holiday party with doomsday (and rebirth) as a theme, you might be wondering? Fair enough, but it’s a useful summary of the diverse emotions we feel as we end eleven years of parties with our favorite people. What started as a small gathering of disparate groups of friends as we were just getting our bearings as (kidless) Chicagoans has grown into an intense labor of love that is easily the highlight of our year.

But labor it is, and we feel our work is done. Energy that was poured into this spectacle now goes elsewhere, primarily to the three lovelies you see below, but also to you all — just in different ways. We know we’re lucky to have such happy and fun-loving friends and we’re immensely grateful you’ve chosen to spend a night of your year with us.

So let’s not focus on the end but rather the fun we’ve had and what comes next. A healthy 2011 to start, followed by more good times, and maybe a beautiful blue spruce in your yard many years from now.

——–

Here’s the full photo gallery.

Curious about past parties?

2009: recap | photos | giftmix | livemix

2008: recap | photos | giftmix | livemix

2007: recap | photos | giftmix

2006: recap | giftmix

2005: giftmix

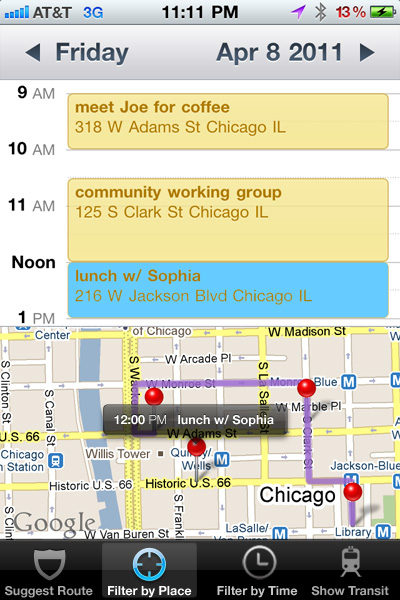

Where’s the map view for my calendar?

Over the holidays, after the deadline for online shipment had passed, I scampered about buying gifts in the real world. Department store staff, clueless bag-laden tourists, hateful too-loud Christmas tunes — it was all misery. But one particular misery seemed avoidable to me: there was no easy way to have a consolidated view of my schedule of shopping stops overlaid on a map. In other words, why if all my calendar events have a place associated with them could I not have a map view of my schedule?

Google has my calendar and obviously they have maps, so where’s the love? Likewise my iPhone. Of course, an app developer has thought of this. Sorta. Arrive will take your calendar events and give you the one-click ability to view an event individually on a map (assuming you’ve loaded anything into the location field.) But one-at-a-time viewing of events on a map really prevents the kind of route optimization that I envision.

The other instance where such a feature would be useful is when traveling — that is, when physical location and distance are less known to the person. It’s hard to plan a day when you don’t know where things are. It was in this situation last week in DC that I tweeted my dismay that such a feature or app did not exist.

So I mocked something up. Really it is just a mashup of the iPhone calendar and map views, but the power of such a feature comes from the route suggestion and ways of filtering. Certainly one should be able to filter by calendar (i.e., show me only work items) or by time (i.e. constrain to 1-4pm today). The more powerful direction would be to constrain a time period’s locations to essentially rearrange your appointments within a given physical radius.

The most powerful function — one that already exists, just not in an integrated way — is to have the system optimize your route for you, suggesting potential reschedules or changes of venue to best fit a day together. Obviously there’s optimization that could happen to reduce transit time, but you could imagine forcing it to show you routes that were most or least walkable (ala Walkscore) or, as Google just recently added, routes that use public transit but minimize your time waiting outside.

The real power here would come from being able to add calendar events directly from the map view — and vice versa. Ideally there’d be no switching out to either standalone app. Or, it could be just another view in the calendar itself: day, week, month, list, map.

Ultimately this is a very specific example of how application developers use old, often physical organizational metaphors (calendars, maps) that silo activities rather than working across data to get at what people are trying to accomplish in the first place. And it isn’t just application developers. Substitute product designers, architects, urban planners, or just about any other design profession and you’ll be able to think of similar instances.

OK, then. Time to build this.

Welcome to City Forward

“I felt the physical city to be a perfect equation for a great abstraction.”

Homage to Victory Boogie Woogie #1, Leon Smith

It’s hard not to see the reasoning behind that quote from the Mondrian-acolyte painter Leon Polk Smith when you learn that he grew up amidst the gridded fields of Oklahoma before moving to New York City.

But it’s instructive in another way. The physical city certainly is the expression of abstract things. The desires of its inhabitants, the collective aesthetic of cultures, the movement of goods, the education, safety, and utilities that strengthen or weaken it.

What’s been missing is a good way to describe that equation. And that’s why I’m pleased to have been a part of the development of City Forward. This site is a first step in aggregating, visualizing, and socializing the abstract vital signs of cities worldwide to permit a better understanding of the world we live in. It’s rich with functionality — honed over many months with amazing feedback from our beta community — to provide a single place to work with the data our cities are opening up.

We’re not alone in this endeavor and we hope to play a critical role in the ecosystem of applications that are making public data more useful, insightful, and actionable.

City Forward has a lot to offer. I encourage you to learn more about what it can do (perhaps watch the video) and to create your own explorations of the data within. Help us find the equations so we can describe a better future for our metropolitan regions.

Oh, the places I’ll be

Leaves are turning, weather’s chilling, Keynote’s revving. Time to hit the road for the fall circuit of conferences, talks, and meeting folks. It’s going to be a crazy slide to the end of the year with two projects launching amidst all this.

Personal Democracy Forum – Europe

Barcelona, Spain

4th-5th October 2010

#pdfeu

City Camp London

London, United Kingdom

8th-10th October 2010

#ccldn

IBM Place Summit

Cambridge MA

Oct. 16-19

Open Cities 2010

Washington, United States

4th-5th November 2010

Full travel schedule here. There’s also a great new social site for tracking conference attendance at Lanyrd.

Lessons from unmaking urban mistakes

Over there, a woman’s walking down a city sidewalk.

She’s doing all kinds of things at once: walking, texting, presumably not being hit by a biker, even perhaps being stalked. Framing this in terms of interaction design, we might think of it as a moment of simultaneous navigation of multiple information interfaces. One of these interfaces is rarely thought of as such; it is the skin of the built world: the sidewalk, curbs, building entrances, shop windows, signage, and welter of moving elements (human and machine) that cross her path. Another is digital: the menus of an iPod, or an application on a smartphone, a GPS map, an SMS keyboard.

Thinking more deeply about only these two — the interface of the street and of her device — it’s clear we’re considering two highly designed modes of interaction. The first by architects and city planners, the second by computer engineers and UI designers. Millions of times a day in a single city these two interaction modalities are layered on top of one another. Now consider that the two communities of practice that develop these interfaces rarely interact, much less formally share knowledge or design in tandem. This is a problem, for both communities partake of city-making.

There aren’t many truly complex things the human race has been making longer than cities which is why it seems irresponsible to me that the participants in what Adam Greenfield calls read/write urbanism would not look to the historical record for insight — especially as we seek to learn from the mistakes we’ve made with the built environment.

But what does this actually mean?

Let’s use one example that currently enjoys a lot of debate and which has had a direct impact on the above pedestrian scenario: urban highways and the various movements to undo them.

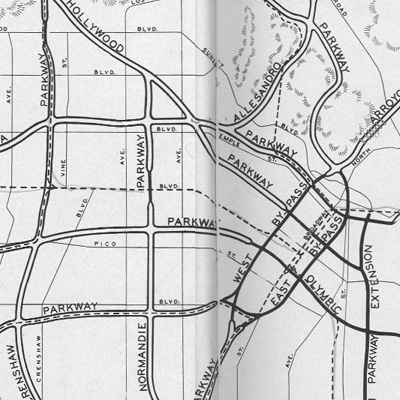

Planning for urban freeways in the first half of last century is often obscured by the white-hot glare of construction that followed from the US Federal Highway Act of 1956. Early 20th century designs emphasized intra-metropolitan mobility, supplementing the dense grid of cities with multiple interchanges, relatively small facilities, and overall attention to harmonizing with the urban fabric (as with multiple central parkways, in the map above). These early freeway designswere built to integrate holistically with other modes of transportation such as railways and bus lines and some even included land redevelopment as part of the construction plan. Because these plans grew from the city itself so, at this point, did the funding mechanism: property taxation, bonds, and special assessment districts (source: JAPA, “Planning for Cars in Cities,” Brown et al, 2009).

This mostly-local method of funding was not adequate to the scale of superhighway infrastructure being planned and so the trajectory of development followed a different course. With centralized funding from the federal Highway Act, itself fueled by new gasoline taxes, the engine of interstate highway construction roared to life. The arteries being built — call them vehicular broadband — eventually stretched through and into the nation’s cities, despite Eisenhower’s initial plan to terminate them at city limits. As the responsibility for construction fell to federal engineers with a different set of priorities than local city planners, nuanced integration of the highways with the urban landscape was largely forgotten.

There was a lot to praise about the Interstate Highway System. High-speed transit and increased mobility changed the very culture of America, permitting easier mobility, increased opportunities for employment, and a broader discovery of the nation itself. But these highways had unintended consequences too. The demand for destinations along the highways induced a period of development that has led to sprawl, exurbia, and an entire class of highway-only development.

In urban areas the effects were compounded by the density of travelers, leading to congestion and pollution. Worst of all from the holistic perspective of the city, urban highways sliced through neighborhoods, disconnecting the human-scale interactions and pedestrian mobility that had defined the street-level vitality of city life. Urban highways often blighted, segregated, or simply erased communities while creating both a physical and psychological barrier to local movement.

By the end of the 20th century some municipalities had come to understand the adverse consequences of urban highways. Portland led the way in 1974 with the demolition of its Harbor Drive Freeway. Other highway removals or reroutings included the West Side Elevated Highway in NYC (after a collapse and contentious public debate), the Park East Freeway in Milwaukee, the Embarcadero Freeway in SF, and most famously the burying of the I-93 highway in Boston known as the Big Dig.

Though all related to unmaking highways, these projects were the result of quite different initial circumstances, engineering approaches, and political machination. And yet each project was an attempt to undo damage done to the urban fabric, to correct a mistake. What might we learn from these examples as we consider the information architecture of cities?

(1) Unintended consequences accompany any design of a complex system.

It would be hard to argue that designers intended the linear parking lots that many of our city freeways have become. They simply did not understand the nature of induced demand: build it and they will come — at which point you’ll learn that you didn’t build it big enough. This is cyclic, congestion-abetting design, however unintended.

Yet I mean not to equate unintended here with negative — at least not entirely. Take the construction of I-93 through Boston’s central business district. There’s no doubt it rended the city in ways its still suffering from, but as the elevated roadway curved northwest at Atlantic Avenue it effectively created a wall between the North End, Boston’s oldest residential community. In important physical and psychological ways, the North End was preserved by this severing of the formerly continuous urban fabric. (While many in “urban renewal” circles saw the North End as blight to be removed, the publication of Jane Jacobs’ Death and Life of Great American Cities is credited with preventing it from being razed as Boston’s West End had been shortly before.)

The North End’s Little Italy neighborhood is arguably the most authentic in the US. The scale of interaction is utterly human, its streets and buildings echos of usage rather than overlaid standardization. One need only look to the Disneyfied Faneuil Hall marketplace just to the south to see what commercial development of a historic area could have meant for the North End. The urban freeway as an unintended factor in historic preservation.

Left: I-93 cutting through Boston's central business district. Right: The Rose Kennedy Greenway built atop the buried highway.

But I-93 has been buried and the barrier to pedestrian movement to the North End is mostly gone. And so is the barrier, perceived or real, to the forces of gentrification and large-scale development that characterize so many historic districts today. The consequences of this remain to be seen.

One might point out that high-performance computing today gives us the ability to model complex system dynamics, simulating possible outcomes of given decisions. But these are early days — and even if a truly comprehensive, responsive city simulation could chart the probability curves for every possible outcome we’ll always have to confront decisions that have implications for a future further out than we can currently predict. (Note that early supporters of the automobile in cities rested much of their argument on a very obvious environmental benefit: cars didn’t leave piles of poop in the street.)

So, while technology does not seem to offer short-term hope for predicting the unintended in complex systems, the invisible architecture of data and services does afford more nimble rearrangement and redeployment than do viaducts of concrete or steel girders, at least in theory.

Cities, of course, are a model of resilience. Buildings learn, the street finds a way, patterns of usage can be reshaped — albeit with the pace of a medium made of brick and mortar. In this way, but with far more speed and flexibility, the architecture of information and services in cities can be built not to prevent unintended outcomes but to enable them. If we agree that inadvertent outcomes are unavoidable in sufficiently complex systems such as cities, then the opportunity we’re presented with in matters of digital design — the lesson, so to say — is that extensibility should be a primary goal. It must, above all, encourage adaptation.

(2) Throughput is not connectivity.

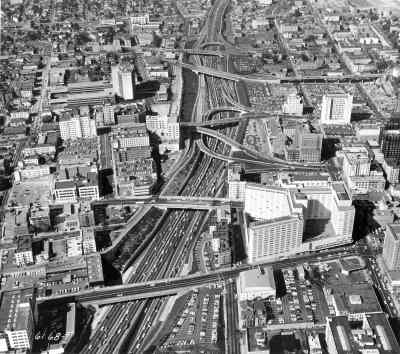

The goals of the Interstate Highway System were simple enough: increased volume of movement at increased rates of speed with fewer accidents. (It is no coincidence that the frontispiece to the 1968 “The Freeway in the City” report to the Federal Highway Administration used this iconic 1909 photo of congestion at Dearborn and Randolph in Chicago.)

It seems likewise simple enough to note that vehicular broadband (a measure of volume-over-time) is not the same thing as mobile connectivity. Yet this misunderstanding — or willful blurring of two very different things — is the mulch from which so many problems with urban freeways grew. Plowing into the dense grid of local thoroughfares, superhighways sacrificed distributed human-scale connectivity of points A through Z for high throughput from point A to point B.

Cities have always been proto-internets of connection and interaction. There’s never only one way to arrive at a destination in a city; multiple routes make cities both diverse and fault-tolerant. But if we extend this analogy — or, rather, make it less of an analogy — to think of cities as information-processing machines, there are some fairly clear lessons to be drawn as we consider communications broadband and the larger implications it has for community connectivity.

Urban waterways, roads, and rail links are all networks of information as well as of goods. There’s value in these networks: information is moved, consumed, changed, combined and created. But there’s a finer level of detail too: at the human scale value is created by observation, being observed, and chance encounter. It’s a physical infrastructure that permits multiple channels of information flow — and this makes for a more efficient, diverse, and redundant system.

In their excellent Information Architecture of Cities L. Andrew Coward and Nikos A. Salingaros make this point most forcefully, assigning the term “fractal loading” to the ability of a single channel (in this case a sidewalk) to carry multiple forms of interaction.

A primary information exchange is a pedestrian going from one point to another. He or she observes things that are unrelated to the primary reason for movement. This information is functional; it can recommend secondary behaviors to the observer who is executing a primary information exchange. A successful city is one in which even simple movements are a rich and rewarding experience. Urban space therefore works by violating the “functional” rule of twentieth-century planning. Successful urban geometry serves a multitude of needs on distinct scales; some strictly functional and others pleasurable.

Walking to an appointment in a European capital (indeed, in most of the world’s cities) can be more pleasant than a drive to achieve the same end in a North American metropolitan area. In the former case, one sees other people, some of whom one might wish to talk to; observing others may provide clues on social currents and interactions; window displays provide information on available products and services, etc….

Fractal loading has the crucial feature that removing the largest level of scale leaves all the other smaller levels of scale intact. Not having to execute a definite errand, undirected wandering in informationally-rich cities allows the visitor to accept recommendations offered by different visual environments, and to discover the results of such movement. It is thus possible to learn the rich and complex “visual language” of an unfamiliar city that has only changed gradually over hundreds of years. By contrast, in a non-fractal deterministic environment lacking all lower levels of scale, if you don’t need to go somewhere, you will most certainly avoid doing so — every movement is a chore, with nothing new to learn.

Non-fractal, deterministic, monofunctional — all descriptors for urban freeways, inhibitors to the kind of freeform interaction that have characterized cities from their inception.

The lesson for digital design for urban spaces is less obvious than it seems. Certainly there’s a corollary that can be made between the coming of vehicular broadband and communications broadband to the inner city. But the repercussions are not the same. Neighborhoods that lay in the path of urban freeways were ripped asunder in a way that fiber optic cables coming through will not do.

What we learn from a privileging of throughput over interconnection is that both are needed. Too often our discussion of the digital divide of connectivity focuses on getting the bandwidth in, leaving how it will be distributed and, most importantly, why it matters as an afterthought. For broadband to catalyze community and development in a city, an architecture that foregrounds people-centric interconnection needs to be laid. (We might call this second kind of digital divide one of digital literacy.) Otherwise it is just a wide pipe of little relevance, such as freeways that stretched to the coasts must have seemed to the people that experienced their ill-effects at street level.

There’s a good deal of funding available for broadband and urban initiatives such as Chicago’s Smart Communities Program seem like the beginning of an understanding of the local, small-scale work required to capitalize on large-scale connectivity. As more of the city itself becomes part of the network and as we move away from thinking of computers and mobile devices as the sole points of tangency of interaction we must remember that throughput means nothing without a diverse set of input/output choices.

(3) Catastrophic failure is an opportunity.

This should sound a chord familiar to those who preach “never waste a good crisis” in our current economic recession and it isn’t particularly novel — but the kinds of catastrophes that have befallen urban freeways is instructive.

Firstly there’s structural collapse. By definition urban freeways are grade-separated; it’s the whole point of permitting faster travel without colliding with local traffic. But this separation incurs engineering complexity and where there’s complexity there’s failure.

The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake damaged transportation infrastructure throughout the Bay Area, prompting dozens of large-scale changes to urban connectors and bridges. One damaged artery, the Embarcadero Freeway, had been the focus of a failed campaign years earlier to demolish it and reconnect the city waterfront to its downtown. Even with the collapse, citizen opposition to demolition remained high (especially among local merchants who feared that the effects of the earthquake on their business would never abate if the freeway were not rebuilt). Eventually public opposition diminished and dismantlement begin in 1991.

The ultimate demise of New York City’s West Side Elevated Highway began in 1973, ironically, when a dump truck overladen with asphalt for repairs to the roadway caused part of the upper deck to collapse. Unintended outcome, indeed.

These failures were moments that demanded city leadership and community involvement. They forced people to think deeply about the effects of city freeways in a way that rarely occurs when a system is functioning nominally (if not optimally). Yet a less obvious form of catastrophic failure — social and environmental — characterizes urban freeways. These are slow-burning effects, and much-contested, but their cumulative effect (vehicle exhaust on public health, economic depression of formerly vibrant areas, cultural fragmentation) often amounts to a more powerful argument for redress than even collapse. And the solutions often solve more than the immediate problem. That is, when the problem is understood as not being solely one of engineering, having wide-ranging effects, the solution can be crafted to address the broader systemic ramifications.

Our urban information architectures have not yet suffered such catastrophe, but we should be mindful that the potential for such in a hyper-connected world of interactive urban elements lends itself even more readily to system failure. Certainly this is a lesson in redundant design, but more than anything it should highlight the infrequent opportunity that large-scale failure presents to those who envision a different way. In addition to planning for system failure of our nascent networked urban spaces we need also to look to the already-built failures of the tangible city for opportunities to redress them in new ways.

(4) All change is system-wide change.

Too often urban roadway remediation focuses narrowly on the merely infrastructural when really what needs undoing are the broader systemic effects.

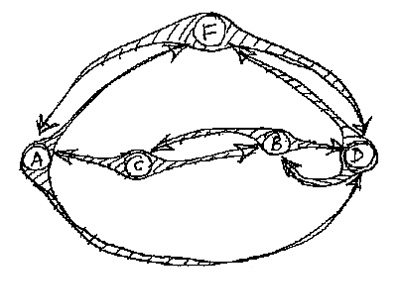

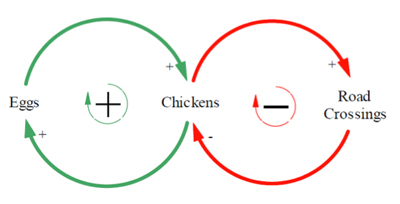

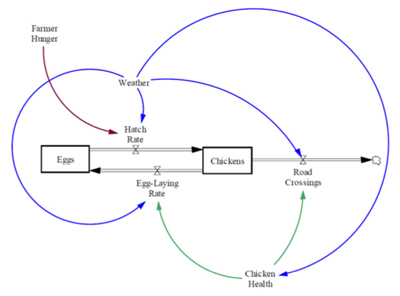

One way to visualize the myriad follow-on effects of changes in a city is the practice of system dynamics. This approach, which uses positive and negative “causal loops” to show interconnection, has a varied history in its application to urban matters, but has received renewed interest of late with the sheer amount of data at our disposal and the maturing of analytical tools.

Consider this often-used example of system dynamics at its most basic.

An increase in eggs forms a positive causal loop because it yields more chickens which also yields more eggs, closing the loop. Yet more chickens invariably leads to more road crossings (a positive vector), but more road crossings (i.e., encounters with motor vehicles) diminish the number of chickens, which closes the loop negatively. For this linked dynamic not to collapse on itself the number of chickens created from eggs needs to be greater than the rate at which they are killed off by getting to the other side of the road. And of course, this chart is unrealistically simplistic.

This loop introduces variables in the process of eggs becoming chickens, including hatch rate and egg-laying rate, which are influenced by farmer hunger, weather, and chicken health — the last two of which are also variables in the frequency of road crossings (i.e., less when the weather is poor or chickens are not strong enough to make the journey).

Now imagine we’re not trying to map chickens crossing roads, but people, goods, and automobiles transiting a network of roads, each with different constraints and affordances. It’s the realm of the hellishly complex — though not necessarily chaotically so. It can be mapped and it is being mapped (trust me on this one), but the point is that, well before the graph looks like a spaghetti bowl, it becomes apparent that there’s no such thing as an independent action much less an independent system in a city.

The Big Dig and burying of the Central Artery in Boston is again instructive. Where once the elevated highway ran right through downtown is now a linear park system known as the Rose Kennedy Greenway. It’s a beautiful, mostly green strip of reclaimed space that, for every instance you’re reminded of how much more they could have done with it, you’re equally impressed that it was done at all.

But it is a perfect example that removing a variable from a system (in this case the highway itself) does not remove its effects. Downtown Boston spent over a half century responding architecturally, psychologically, and socially to the highway that carved through it. Much of this response consisted of ways of actively avoiding it, crafting better views, or leaving the area altogether for less fumy, congested climes. Put another way, the elevated Central Artery caused secondary growth patterns around it like a fencepost that alters the growth of a tree. Remove the post and the tree’s still warped.

The Rose Kennedy Greenway (top image) does not re-establish human-scale transit in the way that existed before the coming of the highway or as it does in the North End (bottom image) because the Big Dig did not concern itself with the secondary effects — the cross-system effects — on the urban tissue surrounding the highway. The Greenway is a phantom limb, a linear park that too precisely echoes a well-landscaped median, which still serves as what Kevin Lynch described as an “edge” (though not nearly in the way that the elevated roadway did).

The bitter irony is that the structures that were built to limn the edges of the Central Artery mostly turned away from it (towards the water or downtown), or thrust upward, or engaged in businesses that had no need for street-level interaction. These remain today and are a primary reason that the Greenway has not fulfilled its potential.

The lesson here? More explicitly than anything in the built environment, technologies of networked interaction cut across multiple systems. Effects ramify outward from causes much more rapidly, potentially causing cascading failure or outage. To understand the city as a system of interdependent systems should be the foundation of any information architecture that seeks, as Adam Greenfield puts it, to enable “lives in a dense mesh of active, communicating public objects”.

In the end — and one reason cities are so endlessly adaptive and unique — all urban tissue is scar tissue. As we co-create the second city of information and services we need only remember that there are plenty of ways to deal with scars, from covering them up to highlighting them as unique differentiators.

(5) It is easy to confuse the use of a system with the need for a system.

When the West Side Elevated Highway in New York City collapsed and was shut down over half the traffic it had formerly carried simply “disappeared”. Despite doomsday scenarios of the traffic that would flood into Manhattan, motorists adapted, changing routes or using other forms of transportation. Being multicursal, the city grid was well-situated to absorb the traffic that remained. Obviously this is much easier to do in a city with rich transit options, but the point is valid nonetheless. In a situation where a medium induces demand the removal of supply often means the removal (or at least mitigation) of that demand. (It causes one to wonder if all the expense of burying the Central Artery in the end was worth it. Might a grade-level boulevard simply have been sufficient?)

Confusing usage with need can be a convenient political tactic as it appeals to a superficial kind of “common sense” (e.g., “I do this every day, so obviously I must need to do this every day”), but more often than not it is merely an avoidance of thinking through consequences or distrust that people can adapt to new circumstances.

Not only does this happen daily in smaller ways as motorists re-route due to road construction, but it overlooks even more radical examples of transportation infrastructure re-use in cities such as the High Line elevated park in New York City. The use of this linear public space has nothing to do with the need to remove dangerous freight traffic from city streets a century ago. A combination of lucky preservation of a private right-of-way, an engaged and creative public organization, and sufficient sources of funding all allowed one use to supplant another, totally irrespective of need.

Churchill supposedly said “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us,” but he forgot to close the loop. Our infrastructure certainly shapes us, fostering a sense of needing the uses for which it was designed. But humans are highly adaptive and as our needs change (due often to other effects of the city-as-system) so our usage evolves, changing the shape of the infrastructure itself.

The lesson here is a twist on the first point, above. Not only must we design for extension and adaptation, but as we embark on an empowerment of citizens through networked technologies we should recall that urban functionality has often been legitimized a posteriori, citing follow-on usage as proof that a particular solution was necessary. (A particularly deadly combination when coupled with the form-follows-funding pattern that doomed the early, localized designs for urban freeways last century.)

This fallacy will be even easier to rest on in the world of rapid prototyping and lightweight deployment of services. The runaway success of Twitter, for instance, is no proof that people needed 140-character status updates. It is proof that Twitter as a service was adaptable enough to accommodate unforeseen kinds of uses. Viewed as a platform rather than a specific application, both Twitter and the elevated metalwork that became the High Line foster new usage in a way that should inform any urban information architecture.

(6) Data alone is not sufficient for problem-solving, but an involved community informed with data just might be.

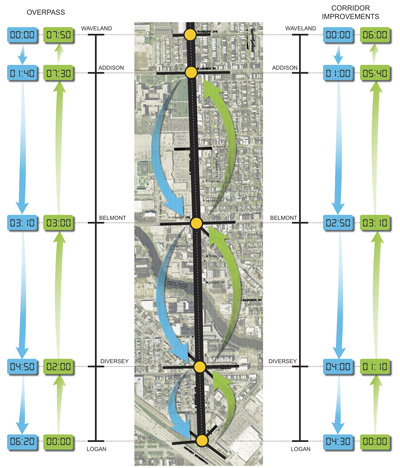

A few weeks ago I attended a Chicago community information meeting for residents of the wards impacted by the structural end-of-life of the Western Avenue overpass. This elevated stretch of roadway runs about 1,000 feet and allows motorists traveling north-south on Western to bypass the light at Belmont and Clybourn. It was originally designed to divert traffic away from the crowds that formed at this intersection, the entrance to the once-great Riverview Amusement Park.

This viaduct forms part of the western edge of the neighborhood I live in. Like much road infrastructure built in the middle of last century, it needs to come down for reasons of material fatigue. The question is whether to rebuild or try something different. The goal of the informational meeting was to express the city’s point of view in a project to build an at-grade intersection where the viaduct now stands.

Like the Central Artery/Rose Kennedy Greenway, much of the environment around the viaduct has responded in the last fifty years by remaking itself into something that no longer needs the pedestrian interaction that so characterized the amusement park intersection before the overpass. One side is big box retail and expansive parking lots (and a massive police station); the other is a somewhat shady assemblage of businesses and residences that do not invite chance inquiry or, if they do, are playing precisely off the hidden nature of their facades (i.e., Underbar and The Viaduct Theater). Adaptability reigns.

The session was eye-opening personally, bringing together local residents, three aldermen, and the engineering firm hired to survey the options. Set up like a science fair project, representatives from the firm were stationed at a dozen or so posters that started with the problem and ended with the proposed solution.

If you have made it this far in the post you will not be surprised to learn that I favor the deconstruction of the overpass. So I was amazed to hear residents ardently supporting it, not for any transportation benefit it afforded them (a good portion of neighborhood residents must drive out of their way simply to get on it), but for the barrier it forms on the edge of the neighborhood. They preferred the way the wall of concrete prevents people from “cutting through” side streets. Other motorists, presumably not neighborhood residents, loved the unimpeded travel, so rare anywhere in the city. Though how much travel time one can save going 1,000 feet over surface traffic causes one to wonder about perception versus reality.

The engineering firm wondered this too and offered the above illustration of projected travel times for the two options, in table form below. (Both are projections because a rebuilt overpass will conform to new standard widths and have different characteristics than the current roadway.)

| overpass | boulevard | |

| northbound | 7:50 | 6:00 |

| southbound | 6:20 | 4:30 |

Clearly the data shows that travel times will improve in new at-grade boulevard, right? Well, yes, but even putting aside the opaque methodology and lack of current travel times in the chart, there are so many factors that were not quantified on the chart as to make it suspect. What happens to the non-arterial street traffic? How might travel times at this intersection be affected by the much more substantial plans for diverting (even burying) the intersection at Fullerton/Elston/Damen? With a newly human-scale intersection, have inevitable slow-downs caused by pedestrians been included in the calculations? Perhaps all of these have been accounted for, but it wasn’t obvious and, most importantly, the data isn’t easily reviewable by the public at large.

I’m still all for tearing down this blight, but I’m less convinced the method of community engagement deserves praise. Few people who held one conviction left with a different one when the meeting concluded and the city was, in the end, free to proceed with its plans (should funding avail itself).

There’s a better way and I believe it can found upon the fertile middle-ground between urban planners and interaction designers — the two communities of practice not noted for close ties at the outset of this post.

We’ve got more data about cities than we know what to do with. It’s lying in archives, published on government websites, being sensed from instrumentation in the environment, deduced from aerial imagery, and built from the ground-up by citizens updating, tweeting, and texting a kind of pointillist painting of city life.

There’s simply no reason that we can’t design tools to bring city-dwellers into a closer relationship with information that can inform their choices. All the raw materials are there: data, visualization, analytics, and tools for socializing one’s insight or commentary. This would not obviate the need for town hall meetings or public presentation of a city’s plans, but it would equalize the power imbalance, bringing a Jacobsian emergent planning ethic to a suasive critical mass that can interact with top-down planning around a common set of facts.

I’ll close by outright quoting Adam Greenfield, a voice in the field of networked urbanism whose echoes you’ve heard throughout this post.

I’ve always taught my students that if you scratch a New Yorker, you’ll find a committed urbanist — someone with intense and deeply-held opinions about the kind of trees that ought to be planted along the sidewalks, or the right way to organize bike parking, or ways to reconcile the conflicting needs of dogwalkers and parents with children in city parks. And the same thing, of course, is true of Mancunians, Singaporeans and Cariocas.

The point isn’t that all of their notions are going to be fair, practical, practicable or even remotely sensible, but that an immense body of pragmatic insight and — more importantly, in my view — passion for the city is going untapped. Pundits, bobbins and bureaucrats talk constantly about improving the efficiency of municipal services, but if improved information is a driver of that efficiency, why aren’t we even trying to gather all the incredibly rich data that’s just lying there, more or less literally begging us to use it? We have the tools, we have the models, we know what they’re good for and where they fall down. It’s past time to build on this experience and bring its lessons to bear on the places we live.

Past time for sure. But not long now.

——–

Further reading:

Frameworks for citizen responsiveness, enhanced: Toward a read/write urbanism, Adam Greenfield.

Highways to Boulevards, Congress for New Urbanism.

The Information Architecture of Cities, Andrew Coward and Nikos A. Salingaros.

Planning for Cars in Cities: Planners, Engineers, and Freeways in the 20th Century, Brian Taylor et al.

Rethinking Urban Freeways, Mark de la Vergne and Anuj Bhandari.

Metropolitan Information Architecture and other mouthfuls

Returning to my info design roots this weekend as I give a talk at the IA Summit in Phoenix on city design. But this one’s a bit different. It’s a call to arms, the other half of a talk I gave last year to architects of the physically-built environment. I’ll be presenting with my grad school colleague and pal, Don Turnbull. Here’s his preview and the full details. UPDATE: Here’s audio from the talk and our slides.

Stretching a bit further, I will be speaking at the Metropolitan Planning Council of Chicago on April 21 on a panel called Talking the Walk: The Importance of Pedestrian-Friendly Public Spaces. I’m honored to share 90 minutes with Sam Schwartz and -Joe Gonzalez- Mike Toolis and am fully prepared for quizzical looks as I try to explain the importance of walkability from the perspective of information network design. Full details here. UPDATE: Recap here.

PS – Mouths-full?