Hey, what’s the food like in China?

Here’s a partial dissection of a truly wonderful lunch in the Imperial Kitchen of the Forbidden City. (Click for notes.)

Today was a scorcher full of meetings in Beijing. I started the day in a coat and tie and ended in an undershirt and sweaty socks. Fill in what you like.

Toot toot

Eternal Egypt is Macromedia’s Showcase Site of the Day. Thanks, Macrodobe! (Remember when Cool Site of the Day was a must-visit web destination in the Netscape era?)

Might as well mention that the site also won a Webby Worthy award recently and, from a while back, a Best of the Web at Museums and the Web 2005.

Toot.

London strong

In World War II the subway tubes were used by Londoners to escape the inferno of Nazi aerial bombardment. Today a new enemy made the Tube itself a hell.

If anyone can look this ghastliness in the face and not blink it is Londoners. Not only because of the decades of domestic terrorism that they have lived with but because of their resolve during WWII. I’m finding myself awed by the British people’s organized and strong response to the tragedy.

Viva Britannia.

Win Ben Stein’s seat

Recently I saw Ben Stein in the airport. He looked like any other business traveller, harried, laden with luggage. Except that he was at a pay phone, which I thought was odd. Who except a philandering spouse, a scrooge, a luddite, or someone who just left their cell at security would use a pay phone? Certainly no seasoned traveller. Imagine my perplexity, then, to see that Ben Stein has written an article full of tips for business travel in the NYT. And I disagree with nearly all of them. I’ll summarize.

- Pay for or upgrade to first class if you can. Well, no disagreement there, except that I would say that often times the exit rows and bulkheads have just as much legroom as first class so if you’re not in it for the free champagne there is often an alternative to upgrading.

- Get the aisle seat. I hate the aisle seat. Your elbows get clocked, you have to get up to let your seatmates out (stow laptop, etc.), and worst of all there’s no good way to sleep since you run the risk of laterally dumping into the aisle or the stranger next to you. Better to take the window where you will be undisturbed and can nuzzle against the wall.

- Use a travel agent. I have no great experiences with travel agents to convey. Unless you are in a complete bind with no access to a computer or direct access to the airline why would you go with an intermediary? Like real estate agents, the era of travel agents having information that their customers do not is coming to an end.

- Make friends with your fellow passengers. Stein advises this so that it is less awkward when you have to ask them to stop kicking you. I disagree. The last thing I want on a plane is smalltalk. Who knows what hell you’re in for on an international trip if you drill a bit too deeply and hit a motherlode of incessant chitchat? And if you have to ask someone to stop kicking you, just ask. Must you have befriended them?

His hotel tips are a bit more in line with my thinking, but it still leaves me wondering: do you trust someone who travels this much and uses a pay phone?

See also: Stuff in my backpack, international edition | Travel tip

Surrogate band

Having watched the four songs performed by the reunited Pink Floyd at this weekend’s Live8 concert I’m now wishing I hadn’t. Oh, it was nice to see all four blokes on stage at once, sure, but there was no sense of real camaraderie or even musical cohesion. The reunion was supposed to demonstrate something along the lines of “if a rock ‘n’ roll band can work things out, can’t we end poverty?”

Waters seemed more like a devoted fan who has been pulled up on stage to sing a few numbers with the band. He was clearly way more into it, melodramatic even, than the other fellas. And, insult to injury, Gilmour has been singing the Waters lines live for so long that they sound a little odd coming from the original. (I know, I know, Waters performs Pink Floyd live too.)

Maybe Pink should have stayed back at the hotel.

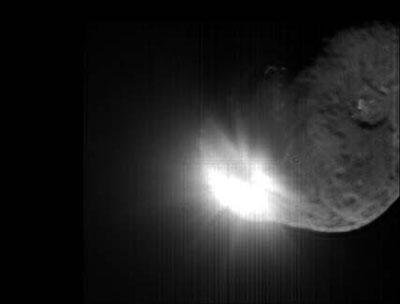

Bang!

The Deep Impact probe successfully slammed into the Tempel 1 comet early on July 4th. Nice fireworks!

NASA hopes to analyze the cometary innards for clues about the composition of the early solar system.

See also video from the impactor point-of-view just prior to collision and

images from the flyby probe, Hubble, and an elated Mission Control.

Happy July 4th, America!

Attention span is overrated

Recently I finished the gigantic Baroque Cycle by Neal Stephenson — a monumental tale of the struggle for sustained progress in an age unaccustomed to it. And by that I mean my reading was such a struggle. 3000 pages — more if you count the 900+ “sequel” published in 1999– is a hell of a task, even for a bibliophile like me. With other reading priorities, book clubs not to get kicked out of, magazines piling up, movies to watch, blogs to cover, and TiVo to play catch-up with I bet it took me two-and-a-half years to read it all. Like Cryptonomicon, The Baroque Cycle was a fantastic, mythopoeic intertwining of real events and people with fictional threads. Not quite historical fiction, not quite science fiction, just geek epic. (Quick test: if this intrigues you, you’ll like the book.) But long. Way long. And long enough that more than a few people I know just said screw it. I’m glad I didn’t. Back to this in a sec.

Right after I finished the last volume, The System of the World, I eagerly began Steven Johnson’s long-deferred Everything Bad Is Good For You. Johnson’s book took me less than a week to finish, mostly on the train. Having followed Johnson’s blog throughout the book’s writing I felt I knew its argument going in. Johnson targets the cherished piece of conventional wisdom which holds that popular culture seeks the lowest common denominator, that it dumbs-down content to hit the widest possible audience. He effectively argues the reverse, that today’s television shows, videogames, computer interfaces, and movies to some degree are all much more complex entities than they were 20 or 30 years ago and that this complexity — the storyline of an episode of 24 or gameplay in Sim City — makes us smarter or, at the very least much better at problem-solving, pattern-matching, and long-term recall. Actually Johnson retains the “largest possible audience” part of the equation, but he suggests that the complexity of contemporary pop culture is aimed at creating that large audience through repeat viewings over time rather than during a single moment of programming as in the past. For example, Johnson argues that the complexity of a single episode of Seinfeld or The Simpsons rewards repeat viewing far more than one of Starsky and Hutch. This argument reminds me of author Michael Joyce’s admonition that these days “a sustained attention span may be less useful than successive attendings.”

Something I’ve not seen addressed in commentary on Johnson’s book is the short section that deals with what he calls the “peripheral effects” of pop culture’s current state that may be seen as “less desirable”. Johnson writes:

Thanks to e-mail and the Web, we’re reading text as much as ever and we’re writing more. But it is true that a specific, historically crucial kind of reading has grown less common in this society: sitting down with a three-hundred-page book and following its argument or narrative without a great deal of distraction. We deal with text now in short bursts, following links across the Web, or sifting through a dozen e-mail messages …. But there are certain types of experiences that cannot be readily conveyed in this more connective, abbreviated form.

He means novels, of course.

You have to commit to the book, spend long periods of time devoted to it. If you read only in short bites, the effect fades, like a moving image dissolving into a sequence of frozen pictures.

Which brings me back to The Baroque Cycle. I’ve already admitted that it took an effort bordering on masochistic to complete such a long work when I rarely have more than a few minutes of time that something else isn’t forcing itself into my cognitive foreground. But what’s interesting is that I experienced Stephenson’s magnum opus exactly as Johnson suggests a novel shouldn’t be: in short bites, short bursts, successive attendings — and I still loved it. Were the The Baroque Cycle a monothematic, page-turning best-seller I probably couldn’t make this claim. But the sheer density of arcs, allusions, ideas, and characters allowed me (or, perhaps drove me unwillingly) to return to it consistently.

This drive didn’t come from a longing to know what happens next — in a story of such complexity things happen somewhat slowly. I’m pretty sure what kept me going was the complexity itself, the likelihood that, even if I could not remember where I was in the storyline (which gotta admit was often), some allusion would trigger a memory from hundreds of pages ago, like picking up on a reference in a Seinfeld episode from one many seasons before. This is Johnson’s precise argument in Everything Bad, but he stops short of extending it to contemporary novels. As with movies, where Johnson notes that only a subset of overall output provides viewers with the structural complexity that most kinds of pop culture demonstrate, Johnson reels in his argument when it comes to today’s written fiction. And I’m not sure why. The Baroque Cycle is an extreme example, but I think, like film, complex narrative exists and, while it might not be the dominant form (thank you Oprah, et al) it certainly partakes of the trend that Johnson describes. More succintly: believe it or not, certain forms of contemporary literature, heirs of the dense novels of the past, actually fit quite nicely into the hectic, multimedia culture of today. Their complexity rewards successive attendings as well as sustained attention.

Sidenote. As I am writing this I see that Kottke posted about Stephenson and Johnson too, though not with quite the same slant.

See also: Urban Library | Wheels and Towers

Resolution review

It’s been six months since I laid out my resolutions for 2005. Let’s review. (It ain’t pretty.)

- Learn how to conjugate Italian verbs in a tense other than the present.

Non completo. - Get a goddamn backhand.

Many lessons later, complete. Whether it’ll hold up in match play is a wholly different matter. - Fall in love with NASA again.

Not yet, but I feel that I could be seduced more easily these days. - Be nice to political bloggers.

Publicly, yes. Lots of private cursing, though. - Learn to match beats when remixing.

Nope. Still a stutter-step crossfader. - When home, watch only high-definition television programming.

I achieved this for a few months. The Cubs season ended my streak though, as only a handfull of games are in HD. - Convert all old mix tapes to MP3.

Not going to happen. Quality too low; quantity too high. - Become able to change my son’s diaper with one hand.

Ashamedly, no. - Avoid LAX like the Black Death.

Done. - Avoid the Black Death.

And done. (But that mole is a little worrisome.) - Get to know my nephews better.

Eh, sorta. - Figure out how to make my own oak switches for the Russian Baths.

Hell, I don’t think I’ve even been to the baths since January.

Well, that’s rather depressing. I wonder what the median success rate is for New Year’s resolutions for the public at large. In fact, I wonder if anyone even remembers them by mid-year.

Like a caterpillar

“Daddy, I’m not going to take a bath until you let me smell the maggots one more time.”

What’s most wrong with this statement?

(1) child giving parent an ultimatum

(2) presence of maggots somewhere in our home

(3) implication that he doesn’t need to bathe unless exposed to maggots

(4) suggestion that I let him smell the maggot-pile in the first place

(5) that he needs another hit of rot-waft