No Kings

High resolution printable version available here.

Hot scalpel summer

Today is my birthday, usually a high point of summer fun. But this summer hasn’t gone quite as planned.

Just a tick up on the prostate antigen scale in my annual physical blood work. “You should get an MRI”, said my doc. Got the test. MRI studied it, “Uh, you should get a biopsy”. Suffered the biopsy. And finally the urologist: “You have cancer”. Quick like that.

Last summer was a lot different. Took an incredible 3-week roadtrip through the American West, vacationed with friends in Turks & Caicos, celebrated my birthday underwater in Curaçao. But this is the ebb and flow of life. Last year riding the surf; this year dragged out by the riptide.

The lesion was small, localized only to the prostate, and treatable, but it was still shocking news. We moved fairly quickly and this past Monday I had the misbehaving cells (and mostly useless host organ) surgically removed. Recovering now, hopefully back to full strength soon with undetectable antigen levels after that. Happy to talk more with anyone about specifics, options evaluated, the scalpel-wielding robot, and such. Hit me up, middle-aged men!

Not calling it a W just yet, but it is late in the game and I’m up by a lot — mostly because of incredible teammates: family near and far, friends, friends who are urologists, friends who beat me at tennis on the regular, and colleagues. You know who you are and how much I appreciate you. ♥️

Oh look, the riptide is dying down. Think I’ll swim back to shore, have a birthday cupcake, and plan some new adventures.

Ghost Ecosystems

I teach a course at CU Denver on urban technologies where, to the bewilderment of most students, we begin by studying a decrepit urban typology somewhat unique to the American West: ghost towns. Where students are expecting robot cars and sparkling sci-fi skylines they get depopulated ruins and crumbling foundations. It takes several sessions before students appreciate why we start this way. The afterlife of towns and cities exposes quite a bit about why they were created, what assumptions they were built upon, and what larger systems they are enmeshed in. If these towns are ghosts, how exactly did they die?

Apart from their educational value, ghost towns in the western US are uniquely fun to explore, little open-air museums of urban decay which defy assimilation into newer development as happens in the east. And it’s not just towns: ghost infrastructure is everywhere, like the time-smoothed scar tissue of historic Route 66 reminding how we stitched together the country west of Chicago in the early 20th century.

More personally, as a relative newcomer to Colorado from the midwest I’ve come to love ghost towns simply for the excuse they provide to explore the region I now call home. Placemaking by way of un-places.

So it seems somewhat obvious in hindsight that I’d inevitably be drawn to dinosaurs, an even more complex and further bygone ecosystem whose presence in the American West is as iconic as tumbleweeds and spurs. Dinosaurs may seem like quite a conceptual leap from ghost towns. But both are sometimes barely visible threads woven into the fabric of our landscapes here, simultaneously a record of engagement with, modification of, and sometimes defeat by the environment itself. This interplay between environment and the creatures that lived in it — indeed were ultimately ended by it — I think accounts for its hold on me, someone with zero paleontology or geology (and very little biology) background. How could an ecosystem as complex as that of the Age of Reptiles, lasting hundreds of millions of years through several extinction events, simply end? Indeed, did it really end? (Hello, birds!) Like ghost towns, the dinosaurs that once prowled (and flew and swam) here have been remade into a kind of modern brand. From gas station logos to baseball team mascots to entire town identities these “terrible lizards” seem endlessly repurposeable.

My first descent into this mild mania actually began not in Colorado but where it all ended off the coast of the Yucatán peninsula.

Vacationing there last year naturally I had to educate myself on the cataclysm of the bolide impact 66 million years ago which brought an end to (almost) all dinosaurs. Once I felt I knew enough I then put together a small lecture, to the chagrin of my family and friends who just wanted beachside rest and relaxation. But that impact! Obviously everything in our locale was obliterated, instantly pulverized, but it was the thought of what the world became in the years and decades after the fiery hellstorm that really got me thinking. A world choked by carbon and airborne particulates, sunless, scorched from heat coming in from the sun but having no way to radiate back out.

How a geologist named Walter Alvarez enlisted his physicist father Luis to figure out just why the boundary in rock sediment separating the Cretaceous period (lots of dinosaur fossils) from the Paleogene period (nary a dinosaur fossil) has levels of the element Iridium 100 times higher than naturally occuring is a story worth reading. Ultimately this layer, called the K-T or K-Pg boundary, and which can be found nearly everywhere on our planet, is the blanket of asteroid material that fell back to Earth after its immolation off the Yucatán — a burial shroud placed gently (and permanently) in the geologic record eulogizing almost 75% of all species at the time.

This was all good fun … until I decided to make a solo mountain bike day trip to Picket Wire Canyonlands in southwest Colorado last year. The trek about killed me — hot, dry, arduous biking on sandy trails. Also I didn’t bring enough water. On the other hand, I had the entire 16.7 trail route to myself, seeing not another soul the whole day. This solitary experience became all the more magical when I arrived at my destination, the largest dinosaur tracksite in North America. 150 million years ago plant-chomping Apatosaurus and flesh-ripping Allosaurus squished their feet into the soft lakeshore here which silted over and hardened into over 1,300 tracks in at least 100 separate paths criss-crossing every which way. I dismounted my bike right in the middle of it all, sat on the sun-baked rock, reveled in a total lack of cell signal, and tried to imagine what the place would have looked like — sounded like, smelled like! — as the herds slopped through.

And then I was hooked. How could I not learn more at this point? I had placed my foot inside the footprint of another living creature from the Jurassic period out on a bike ride just a few hours from my home.

Sure, Sue the T-Rex was found in South Dakota. Montana has the infamous Hell Creek Formation. Utah gave us the raptor that successfully retconned Spielberg’s originally ludicrous depiction of Velociraptors in Jurassic Park. Even Kansas can flaunt its one-time Western Interior Seaway and basically all the great marine reptile and pterosaur specimens.

But Colorado is the state that I think most fulsomely embraces its dinosaur history. Here are some highlights.

The Triceratops Trail (officially the Parfet Prehistoric Preserve) on the edge of Golden offers an easy walk through former clay mining trenches that have exposed all kinds of interesting dinosaur tracks. Triceratops is confirmed with possible Tyrannosaurus and Edmontosaurus. Easily as interesting are trace fossils of birds, small mammals, beetles, palm fronds, and even (arguably) raindrops. The site abuts an active golf course. It’s a bit jarring to see humans frolicking around the perfectly engineered invasive species of putting green grass, then turning around to face a 100+ million year old wall of dinosaur tracks. I wonder which will outlast the other?

A lizard basks on the Triceratops Trail separated from its clade-mates by a mere 231 million years (evolutionarily). 19th century depictions of dinosaurs took a lot of inspiration from their lizard cousins. We know now that there was very little tail-dragging and tongue-flicking. Our modern dinosaurs are birds and once you note that you can’t unsee it.

In a stroke of geological luck in the Late Cretaceous what was once flat beachfront wetland was jacked up at an angle by two tectonic plates sliding under one another called the Laramide Orogeny. This angling gives us some of the most stunning formations in the foothills (think Red Rocks Amphitheatre) but also provides a kind of outdoor exhibit space perfect for humans strolling by to view all its embedded fossils. One of the best hikes around if you’re into ichnology (the study of the fossilized tracks, trails, burrows and excavations made by animals).

It takes a trained eye (which I do not have) to spot some of these tracks. Points to the curators of Dinosaur Ridge for making the good stuff obvious. Here’s a rare Velociraptor track. That hoop is maybe 4″ in diameter, a reminder that true Velociraptors were the size of turkeys (and feathered like them too). Definitely wouldn’t want to tangle with one, but also not the big scaly door handle-operating baddies from the movies.

The Morrison Natural History Museum located near Dinosaur Ridge is a standout. Intimate, chocked with great local fossils and full of helpful one-on-one guides (all of whom are city employees — go off, Morrison!), it is exactly what a museum should be. Being mostly the display and preparation facility for fossils discovered over at Dinosaur Ridge, you get to see the real thing. Not many casts here. Highlights include the story of the discovery of the first Stegosaurus nearby, infant dinosaur tracks surrounded by giant sauropod imprints (how did they not get trampled?), an outdoor dig pit, and pointers to plant survivors of the K-Pg extinction. As you can see from the above video, part of the exhibit space allows you to sit down and try your hand at removing rock matrix from an Apatosaurus skull with a dental drill. If you’ve got good eyesight, a steady hand, and an infinite amount of patience, perhaps fossil preparator is the job for you?

In far northwest Colorado straddling the Utah border is Dinosaur National Monument. I visited in the winter so it was just me and the ranger and several thousand jumbled dinosaur bones. The highlight is certainly the “Wall of Bones” which the park has left in situ and built a lovely enclosure around called the Quarry Exhibit Hall. Like Dinosaur Ridge, it’s tilted at a perfect viewing angle thanks to tectonic subduction. All these bones in one place it is pretty confidently theorized come from an ancient stream that just washed them all into one place. Checking off another box on the things-that-appeal-to-John list is that Dinosaur National Monument is an official International Dark Sky site. There’s no artificial light anywhere. Fossils by day, stargazing by night. I must return. (Zoom into the shirt to see the best gift I have ever been given.)

T-Rex gets all the love, but the earlier Allosaurus was every bit the terrifying carnivore, if slightly smaller. Check out the horns on its brow where evolution apparently decided “death machine but more demonic”.

The Colorado town nearest the national monument and formerly known as Baxter Springs renamed itself Dinosaur in the 1960s and they have not looked back. Pictured is a tyrannosaur wanting nothing to do with the soft touch of a carwash. (The town’s counterpart on the Utah side, Vernal, arguably takes its terrible lizards even more — or less? — seriously. Every other business is festooned with some form of fiberglass saurian.)

See that missing tip of the Diplodocus vertebra she’s pointing to? Paleontologists agree that’s what happens when a giant theropod chooses you for a meal. This attack would have taken out a sizable piece of tail meat (and of course part of a bone), but clearly the Diplodocus lived another day. That is, until it was entombed in the mineral-rich sediment that allowed it to fossilize and be presented at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Bad day for ol’ Diplo, good for us.

Over Grand Junction way the Dinosaur Journey Museum has some striking specimens including a sauropod femur with deep claw marks, properly feathered dinosaur models (which, maybe it was the animatronics, audio, and lighting, but to me floofy dinos are somehow even more chilling than lizardy dinos), and the skull starring in your next nightmare from Diabloceratops. Step back, Allosaurus. Your horns ain’t nothin’. Their working paleo lab, pictured above, was the largest I have seen so far.

So that Western Interior Seaway whose west coast provided such good fossil-making sediment on its shores also delivers up some incredible marine reptiles and pterosaurs, which, while neither are dinosaurs taxonomically, are related contemporaries and just as fascinating. Most of what’s on display at the Dinosaur Resource Center — located a short way into the mountains up from Colorado Springs — was unearthed by the for-profit Triebold Paleontology company who runs the center, a unique business model to say the least.

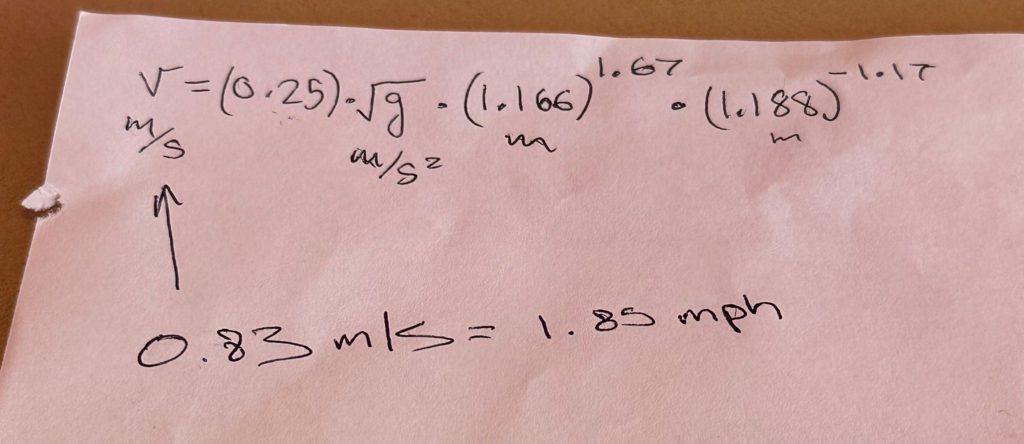

All of this is just dilettante paleontology of course. I don’t even know that I qualify as an enthusiast. Admirer, maybe? Paleontology is so radically cross-disciplinary there are entry points from dozens of domains: geology, biology, botany, the visual arts, math, data science, etc. As an example, my son, a physics nerd, was intrigued by our ability to measure footprint size and stride length to accurately calculate pace — a glimpse into not what the dinosaur was but what it was doing. And that’s just extraordinary.

It’s not all about the science, of course. The idea for Dinger, the mascot of the Colorado Rockies baseball team, hatched during the construction of Coors Field when some dinosaur bone fragments were unearthed. It’s impossible to know if those fossil bits came from a Triceratops, though scientists are fairly certain they come from an herbivore (which the ceratopsians were). Somehow Dinger is bipedal, but we’ll let that slide as he’s one of only two (non-avian) dinosaur mascots in all of professional sports.

I’ve found dinosauriana in the strangest places. An otherwise-average Best Western in a Denver suburb with legit fossil casts, vintage paleontology gear, and weekly lectures? Sure why not. How can you not love its murals depicting the feud between 19th century paleontologists Edward Cope and Othniel Marsh of “bone wars” fame? These fellows would actually sabotage each others’ digs they hated each other so much. Immortalized now on the side of mid-tier hotel chain. Nice work, gents.

It’s all gone now, of course. The actual dinosaurs, that is. Paleontology itself is having a bit of a golden age, if the pace of scientific discovery is any measure. But the mindboggling diversity and longevity of these vertebrate marvels ended 66 million years ago. Yes, with a bang, but also likely with a whimper. One ongoing area of scientific research and debate is just how long it took everything to die after that very bad day off the Yucatán. While there are no dinosaur fossils found above the Iridium Layer, the millimeters of strata that make up its layers are measured in millions of years. It’s possible dinosaurs survived for a while after the impact, but what’s nearly certain is that it was radical changes in climate that ultimately ended their particular ecological niche. (Indeed climate change is the culprit in all our planet’s mass extinctions, including the worst one of all which gave rise to the world the dinosaurs inherited.) Today paleontology is not just digging up scary beast bones or fodder for big screen thrills. It’s proof that our global ecosystem is a fragile one, an eschatology written in mineralized organic remains. Towns become ghosts; seemingly invincible living systems become ghosts. Paleontology isn’t about the past, ultimately; it’s a prediction.

If you’d like to delve further I recommend the Apple TV+ documentary series Prehistoric Planet (two seasons so far), the Terrible Lizards podcast, and a few good books.

Holiday Frights 2022

(Of note, I consider Gremlins a Christmas horror movie, fight me.)

Welcome to another annual edition of recommendations for your spooky Christmas needs. (Click here to skip right to the reviews.)

Last year I mentioned the few contemporary remnants of the Victorian-era love of wintertime ghosts, but the linkage between short, dark days and the urge for flesh-tingling storytelling goes back a lot further than that. Shakespeare in A Winter’s Tale (1611) notes “A sad tale’s best for winter. I have one. Of sprites and goblins.” Yule logs, mistletoe, the Christmas tree itself — all pre-Christian celebrations of the winter solstice, symbols of a time for gathering in a space where you could only see to the limit of a fire’s flame. And what to do around this fire, huddled close? Tale-telling, naturally. Those tales, as the setting rather begs, historically have been about ghosts and other haunts. This tradition wound its way into Christianity and the modern era, as Colin Fleming notes as a series of

… readings for the season—but not really of the season … a rather more pleasing terror—the ghosts, even when they mean to avenge themselves upon us, also seem to have dipped into the nog a time or two, with their own playfulness in evidence. Sure, they can kill you, but they do so with a joke or two at the ready. These are the short days of the year, and a weird admixture of pagan habits and grand religiosity obtains. There is also booze. People didn’t have TVs: people drank, people got to telling tales, someone told a tale and someone tried to tell a bigger one, and then, lo, we got a whole ghost story Christmas tradition.

Holiday ghosts were fading away by the early 19th century until Charles Dickens famously brought them back as time-traveling tour guides in a grand morality tale. A Christmas Carol is the last major vestige — a tomb marker, if you will — of a tradition that was far weirder and scarier than any of Dickens’ four ghosts. And yet, A Christmas Carol is part of the cultural atmosphere of Christmas, there even when it isn’t in the foreground: scrooge-as-a-verb, being shown how behavior can spawn multiple timelines, the inspiration for the Grinch, and countless adaptations (including this year’s Spirited with Ryan Reynolds and Will Ferrell — worth a watch). It’s embedded in our childhood psyche in a way unlike any Halloween ghost story.

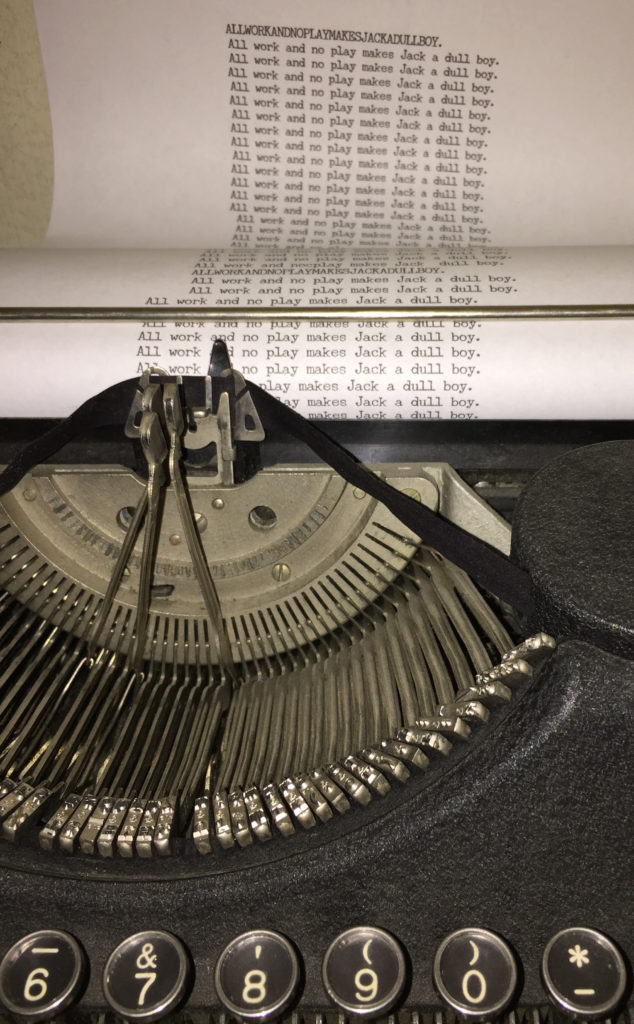

Here’s my personal proof. Christmas Day, 1982. My siblings and cousins retreat to the basement to create our own adaptation of Dickens’ classic. It was the dawn of VHS cameras, the noonday of wood-paneled suburban decor, and the dusk of my short career as a playwright. This grainy, budget-less masterwork, a Christmas gift to you, will likely be the most disturbing thing you watch as a result of this newsletter.

You may think that Halloween has the monopoly on horror media, but it isn’t even close (at least in the USA). There are hundreds, possibly thousands, of Christmas-themed horror movies from barely watchable home movies (ahem) to legit masterpieces — the true legacy of those bards of yore and their campfire frights. Let me tell you about some.

One day at a time

Friends! I turn 50 years old on August 4. I’ll pause for old person jokes, but please speak up.

50 is an arbitrary milestone, sure, but I got myself a pretty great gift and I’d like to tell you about it. August 4 will mark 1,000 days since I gave up alcohol. It’s been the best thousand days of my life overlaid right on some of the worst thousand days we’ve had as a human species (battling a virus species). That this sobriety milestone happens on my 50th birthday is a coincidence. But maybe there’s no such thing as a coincidence?

The story of my road to sobriety is a long one, one I am happy to share at length with anyone — especially those whose relationship with alcohol is unhealthy. Here’s the short version: I accepted that I had a problem with alcohol — let’s call it what it is without stigma: alcoholism — just after Halloween 2019. Halloween is my favorite holiday of the year and also my son’s birthday. So, naturally, a terrible time to crater. But crater I did, which was exactly what I needed. Went away for help for quite a while … and then the pandemic happened and I came home to a new life. The world was in lockdown, but I felt fully unlocked. It was especially eye-opening time, those early days of sobriety, when the world itself was coming to terms with the lessons of recovery: re-connecting with simple life-affirming things, not projecting too far into an unknowable future, living one day at a time and chalking those single days as victories. It was as if all of society for a brief period was supporting my own early, delicate recovery.

It’s no longer early; it’ll always be delicate I suspect. So’s life. But each day is a great day and that feels better than any buzz ever did. Not gonna name names, but I have received a lot of help and love from family, friends, and then-strangers in this journey. You know who you are and you know how much I appreciate you.

To alcohol I say, no hard feelings. We just didn’t work out, you and I, when I realized I didn’t love you. Totally cool with your relationship with others. Best of luck!

So, yeah, one day at a time adds up. Sometimes it adds up to 50 years (thanks Mom and Dad!); sometimes it adds up to 1,000 days of clean living. I intend to keep adding.

Why am I telling you this before my actual birthday? Because I got myself another gift: this fundraiser for a cause very close to my heart. 🪸

The Marhaver Lab — run by marine biologist, science communicator, Georgia Tech grad, and friend Kristen Marhaver — is a research outpost based in Curaçao in the southern Caribbean. The work of Marhaver Lab is aimed squarely at helping solve the problem of declining biodiversity of the world’s coral reefs. This is critical work: coral reefs are foundational elements of our oceans’ larger ecology. When reefs thrive, fish populations thrive. When fish populations thrive, the planet (and humanity!) thrives.

I don’t think anyone gives gifts for a person turning 50, but if you’re so inclined your support of Marhaver Lab would mean a lot to me. More information and tax-deductible donations accepted here.

Thanks for reading! Hope you can donate. On to the next day, with gratitude!

Gravid With Decay, love letters to a genre

Hello friends! Last year when the lockdown started, I watched a lot of movies. Most of these were what’s considered horror or closely adjacent to it. I wrote about almost everything I watched (and why I think it was as much an immune response to the pandemic as antibodies).

That long post, though, was the summation of months’ worth of biweekly emails sent among friends just sharing recommendations and thoughts on movies we were watching. I loved writing those and was kinda sad when we wound it all down.

Welp, we’re not out of the pandemic and I’m not done sharing short thoughts on horror via email. Like any good monster, the reviews are back, undead. Also like any good monster, you never quite know when it will appear (OK, fine: never more than weekly). Sign up at Buttondown or below. (Need a preview?)

Cityfi: yeah, it’s a verb

Cityfi? Like Wi-Fi? Or like … unify? Is it a thing or an action? I’m here to tell you it’s a verb. Everything about the work Cityfi does is about motion, progress, and change. So here’s a little update on my movement, as I take leave from this small but mighty company.

July 2016, Before Times: my family and I had just arrived in Denver after a cross-country relocation. It was a fresh start geographically but also professionally. With my friend and former colleague at the City of Chicago, Gabe Klein, we started a new company with the amazing Ashley Hand. It was the birth of the urban change management consultancy Cityfi.

Our hunch that both the public and private sectors could use guidance navigating the rapidly-evolving realms of urban mobility, data analytics and privacy, equitable services, and climate change resiliency (to name just a few) was proven correct. We were off to the races and working with great clients all across the country and globe.

Cityfi is stronger than ever now, coming up on five years in. With the addition of partner Story Bellows and some amazing senior staff, we’ve created a first rate team, a portfolio of work, and most importantly a reputation for responsive, thorough consultancy that seems to be needed more than ever.

There’s never a great time to move on from something you love. (I know this; I left Chicago … just as the Cubs were about to win the World Series.) But now’s my time to step forward from Cityfi.

Obviously this has been a past year of change and uncertainty, but for me the relative slowdown of life — limited physical interaction and travel, whittled-down life patterns — has brought what I think is clarity of purpose, or at least time to listen with less background noise. The signal coming through isn’t completely decoded, but I’ll let you know what it says when it is.

For now, I have a class to teach and a brand new smart cities certificate to help manage at the University of Colorado Denver (as, ahem, a scholar in residence). I remain involved locally as the board chair of the Colorado Smart Cities Alliance (an early Cityfi initiative and one of which I am most proud).

While that pride exists for a lot of what we built at Cityfi and I’m confident that its future is bright, the main emotion I feel is gratitude. I am not sure I could have made the transition to a new life in Colorado without the support of my partners. For that I am immensely grateful.

Lastly, deep thanks to the clients, associates, and affiliates who made these past years of work engaging and meaningful. Thank you all for treating Cityfi as a verb. Here’s to your continued movement — healthy, happy, and ever-forward.

Coral brickscape

I’m a coral nerd and an unrepentant adult fan of LEGO bricks, so I figured why not attempt a completely instruction-free build of a squishy, curvaceous reef out of hard plastic 90° angles.

Certainly I get the irony of making a model of corals from non-biodegradable plastics, but maybe that’s the point (and part of the point of keeping a huge tank of actual corals): the need to create a microcosm of something that’s rapidly disappearing seems more urgent, even if it’s only a creative pastime.

And what a pastime it was. Early on in my musings of how to do this I realized there was no way I could find the bricks I thought I needed just sorting through the 100,000+ loose bricks in the dozens of tubs and bags they were randomly collected in. This launched an effort at organization and general de-crufting that deferred the actual reef project for months.

The sorting itself was, in a way, part of the design process. Touching every single brick we own (in every possible orientation, decontextualized from its originally-intended purpose) gave me a millisecond per brick to consider how it might be used to simulate the crazy shapes that reefs take.

And that was the real challenge; there’s nothing rectilinear about coral. If it isn’t a swaying mass of tentacles, polyps, and pulsing mouths it’s a bleached Iron Throne of jagged, fractal CaCO3. I took a lot of inspiration from techniques for making botanical models (plants, flowers, etc) but also from the advanced facade decorations included in LEGO modular architecture sets. Basically, I catalogued as many of the ways of getting bricks to assume odd or semi-random angles while still being affixed to one another. Didn’t hurt that I could just stare at my own tank of beasties for inspiration when I got stuck.

There is an actual LEGO coral brick, but I ended up not using it much as it’s really a distillation of what we generically think coral looks like. In the end it was far more fun to repurpose minifig hairpieces, radar dishes, trumpets, chalices, carrots and ice cream scoops. Mounting all that was mostly an exercise in SNOT (“studs not on top”) design, using nearly every brick made specifically for that purpose and a ton of techniques culled from the LEGO nerdweb.

There’s a lot going on in this ecosystem. The main subdivisions left-to-right are a vibrant reef section, the marine science and bleached reef middle section, and the “all the things on the seafloor” section which includes a shipwreck, hydrothermal vent, and whale fall. Other items include a transoceanic fiber cable (with repair technician attempting to bring broadband to your continent), wreckage from Oceanic Flight 815, Aquaman fighting Black Manta, a couple shy mermaids, the Antikythera Mechanism, a diver as skeletonized as the whale, human trash in the bleached patch (including an actual broken piece of ABS LEGO plastic), and a steampunk Diver Dan. See if you can find them all. (Here’s the full set of photos at Flickr.)

It’s all now mounted on a lower shelf in my home library, part of a larger cityscape and sea. The ocean surface needs a lot of work, but for now I’m going to turn to the relative comfort and trance-like ease of building a set with actual instructions. Freeform and organic is a lot of work, you know?

What I found digging through 41 years of LEGO bricks

A few months ago I embarked on the Sisyphean task of organizing the LEGO collection in our house. I mean, let’s be truthful: it’s my collection, but my children have historically been the happy recipients of sets that I have ultimately folded into the larger pile of bricks over time. And what a long time it has been collecting, disassembling, and pretty consistently enjoying this big mess of ABS plastic.

My first memory of a LEGO set is the Galaxy Explorer from 1979 (which I rebuilt a few years ago). Since then I’ve never consciously thrown any bricks out, though certainly some have been lost and many have been broken. Using weight as a rough approximation for quantity we have well over 55,000 loose LEGO pieces. (Closer to 100,000 if you count pieces actually residing in built sets and MOCs.)

The actual sorting through all that has been fascinating and therapeutic, equal parts mind-numbingly meditative and joyful. But perhaps the most interesting part of this whole process has been sifting out all the junk in the bins that is not LEGO. And there was a lot of it, specifically 8.325 lbs of accumulated detritus of my youth (with some pieces from my kids’ younger days too). Sieving through it was a kind of autobiographical archaeology, a forensics of youthful amusement.

Inspired by Amsterdam’s dredging of a few canals to install a new subway line where they uncovered and displayed centuries of things from everyday life, I thought I’d lay out a small selection of the non-LEGO trove here. It’s an incomplete picture of how I grew up, but a picture just the same.

- metal Gatorade cap from when it was sold in glass bottles

- Native American arrowhead from a felt display box I had from a trip out west — easily my favorite find

- Ace of Spades, mutilated

- Playmobil figures, many balding as I am

- Little Green Men and various figurines of people shooting things

- Play-Doh container cap

- hair barrette and tie (my sister’s)

- toy rings

- dice

- magnetic refrigerator letters

- spent toy gun caps

- all manner of broken LEGO

- counterfeit LEGO

- game pieces — I think The Dark Tower is in here, loved that game (which is coming back!)

- puzzle pieces

- hockey playing card — of note, I never followed hockey in my youth

- air hockey puck — also of note, we did not own an air hockey table

- lip gloss — possibly mine, probably my sister’s

- marbles and bouncy balls

- pennies with a lot of verdigris

- tickets (likely from Showbiz Pizza)

- a Paris Metro ticket (huh?)

- cassette tape labels — used, naturally!

- dominoes

- note fragment in what I think is my sister’s handwriting: “Adolescn .. any perio … tends to b … by a group”

- embossed label strip — loved those things

- post-it note w/ scrawl — looks like testing a marker

- a Toys ‘R’ Us tag for $29.99 — wonder what that was?

- various stickers

- a thimble

- lotta crayons and writing implements

- Matchbox car and USAF Blackbird

- toy monorail — transit, baby!

- Nerf dart

- a magnet that has pulled together random metal bits

- an Enter key

- a half-gnawed pretzel stick, easily 30+ years old

- part of a in-ear headphone

- other unidentifiable cruft

Not exactly panning for gold, but there’s definitely a Toy Story-esque nostalgia at play. Literally play, which is the only consistent throughline with all this junk. My youth was certainly filled with electronic gadgets, video games, and computers — but none (or very few) of those have lasted. What remains in this re-assambled time capsule are the simpler items, perhaps the best items. A collection of fragments shored against, if not ruin, then the ruinous loss of innocence. I’m not throwing any of this away.

A year underwater

Last year, as Chicago settled into a colorless, lifeless winter freeze, I decided to take up Scuba diving seriously. Maybe it was escapism, envisioning myself floating above tropical reefs, the very opposite of the blizzardscape outside.

Great Barrier Reef, Cairns, Australia

There were other reasons for diving into an expensive hobby I had basically no time for. I suppose I’d finally come to terms with the fact that I would never actually be an astronaut. Diving seemed like a compromise. The sea’s a fairly alien world, as unmapped as the moon, and if you get your buoyancy right diving is about as close to flying (or bouncing around in microgravity) that I was ever going to get.

Poor Knights Islands, Tutukaka, New Zealand

It wasn’t completely out of the blue. I’d maintained a saltwater reef tank for about three years and had a more than beginner’s understanding of the complexity and beauty of marine ecosystems. Part garden, part science fair project, part sea creature death match arena: my reef tank was the gateway drug to Scuba. I was no longer content to sit outside the glass.

Molokini Crater, Maui, Hawaii

I knew going in I wasn’t interested in great depth. Not so fired up about shipwrecks. No desire whatsoever to jump through an ice hole or into mazy caves. I wanted coral reefs with all their bottom-up symbiosis and toxin-spewing brutality, exotic colors and improbable shapes, undulating tentacles and ship-slicing skeletons.

Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo, Mexico

Through luck, vacation time, and some trips tacked on to work travel I actually got to experience quite a bit this year: a sub-tropical way-stop of the East Australian Current at the tip of northern New Zealand; cliff-clinging life off the Amalfi Coast in Italy; the Crayola box coral gardens off Cozumel, Mexico; the mind-bending diversity of the Great Barrier Reef in Australia; and the playground of endemic species in Hawaii. Even did a wreck dive in the chilly but crystal clear waters (thanks, invasive mussels!) of Lake Michigan. Here’s a map.

The Wells Burt Wreck, 42.0458° N, 87.6180° W, Lake Michigan

There’s no way to make sweeping statements about the health of coral reefs with as (relatively) few dives as I made this year, despite the somewhat globe-spanning locales. But it certainly is true that reefs, like rainforests, are the coal mine canaries of climate change. I have personally wiped out entire ecosystems in my aquarium with two degree temperature changes. The ocean, of course, is far more resilient than a tiny tank, but it is clear that wild reefs themselves are under stress. We’re in only the third coral bleaching event in history and, while I saw some of the world’s best (and healthiest) coral, there was death and decay all around.

Cozumel, Quintana Roo, Mexico

It’s a wonderful world under the waves. Here’s hoping you get a chance to peek under them too sometime.

Near Praiano, Amalfi Coast, Italy

(The photos in this post link to larger versions which get you to fuller galleries. And if you’re interested, dive log details are available by clicking the place name in the photo caption.)