Ghost Ecosystems

I teach a course at CU Denver on urban technologies where, to the bewilderment of most students, we begin by studying a decrepit urban typology somewhat unique to the American West: ghost towns. Where students are expecting robot cars and sparkling sci-fi skylines they get depopulated ruins and crumbling foundations. It takes several sessions before students appreciate why we start this way. The afterlife of towns and cities exposes quite a bit about why they were created, what assumptions they were built upon, and what larger systems they are enmeshed in. If these towns are ghosts, how exactly did they die?

Apart from their educational value, ghost towns in the western US are uniquely fun to explore, little open-air museums of urban decay which defy assimilation into newer development as happens in the east. And it’s not just towns: ghost infrastructure is everywhere, like the time-smoothed scar tissue of historic Route 66 reminding how we stitched together the country west of Chicago in the early 20th century.

More personally, as a relative newcomer to Colorado from the midwest I’ve come to love ghost towns simply for the excuse they provide to explore the region I now call home. Placemaking by way of un-places.

So it seems somewhat obvious in hindsight that I’d inevitably be drawn to dinosaurs, an even more complex and further bygone ecosystem whose presence in the American West is as iconic as tumbleweeds and spurs. Dinosaurs may seem like quite a conceptual leap from ghost towns. But both are sometimes barely visible threads woven into the fabric of our landscapes here, simultaneously a record of engagement with, modification of, and sometimes defeat by the environment itself. This interplay between environment and the creatures that lived in it — indeed were ultimately ended by it — I think accounts for its hold on me, someone with zero paleontology or geology (and very little biology) background. How could an ecosystem as complex as that of the Age of Reptiles, lasting hundreds of millions of years through several extinction events, simply end? Indeed, did it really end? (Hello, birds!) Like ghost towns, the dinosaurs that once prowled (and flew and swam) here have been remade into a kind of modern brand. From gas station logos to baseball team mascots to entire town identities these “terrible lizards” seem endlessly repurposeable.

My first descent into this mild mania actually began not in Colorado but where it all ended off the coast of the Yucatán peninsula.

Vacationing there last year naturally I had to educate myself on the cataclysm of the bolide impact 66 million years ago which brought an end to (almost) all dinosaurs. Once I felt I knew enough I then put together a small lecture, to the chagrin of my family and friends who just wanted beachside rest and relaxation. But that impact! Obviously everything in our locale was obliterated, instantly pulverized, but it was the thought of what the world became in the years and decades after the fiery hellstorm that really got me thinking. A world choked by carbon and airborne particulates, sunless, scorched from heat coming in from the sun but having no way to radiate back out.

How a geologist named Walter Alvarez enlisted his physicist father Luis to figure out just why the boundary in rock sediment separating the Cretaceous period (lots of dinosaur fossils) from the Paleogene period (nary a dinosaur fossil) has levels of the element Iridium 100 times higher than naturally occuring is a story worth reading. Ultimately this layer, called the K-T or K-Pg boundary, and which can be found nearly everywhere on our planet, is the blanket of asteroid material that fell back to Earth after its immolation off the Yucatán — a burial shroud placed gently (and permanently) in the geologic record eulogizing almost 75% of all species at the time.

This was all good fun … until I decided to make a solo mountain bike day trip to Picket Wire Canyonlands in southwest Colorado last year. The trek about killed me — hot, dry, arduous biking on sandy trails. Also I didn’t bring enough water. On the other hand, I had the entire 16.7 trail route to myself, seeing not another soul the whole day. This solitary experience became all the more magical when I arrived at my destination, the largest dinosaur tracksite in North America. 150 million years ago plant-chomping Apatosaurus and flesh-ripping Allosaurus squished their feet into the soft lakeshore here which silted over and hardened into over 1,300 tracks in at least 100 separate paths criss-crossing every which way. I dismounted my bike right in the middle of it all, sat on the sun-baked rock, reveled in a total lack of cell signal, and tried to imagine what the place would have looked like — sounded like, smelled like! — as the herds slopped through.

And then I was hooked. How could I not learn more at this point? I had placed my foot inside the footprint of another living creature from the Jurassic period out on a bike ride just a few hours from my home.

Sure, Sue the T-Rex was found in South Dakota. Montana has the infamous Hell Creek Formation. Utah gave us the raptor that successfully retconned Spielberg’s originally ludicrous depiction of Velociraptors in Jurassic Park. Even Kansas can flaunt its one-time Western Interior Seaway and basically all the great marine reptile and pterosaur specimens.

But Colorado is the state that I think most fulsomely embraces its dinosaur history. Here are some highlights.

The Triceratops Trail (officially the Parfet Prehistoric Preserve) on the edge of Golden offers an easy walk through former clay mining trenches that have exposed all kinds of interesting dinosaur tracks. Triceratops is confirmed with possible Tyrannosaurus and Edmontosaurus. Easily as interesting are trace fossils of birds, small mammals, beetles, palm fronds, and even (arguably) raindrops. The site abuts an active golf course. It’s a bit jarring to see humans frolicking around the perfectly engineered invasive species of putting green grass, then turning around to face a 100+ million year old wall of dinosaur tracks. I wonder which will outlast the other?

A lizard basks on the Triceratops Trail separated from its clade-mates by a mere 231 million years (evolutionarily). 19th century depictions of dinosaurs took a lot of inspiration from their lizard cousins. We know now that there was very little tail-dragging and tongue-flicking. Our modern dinosaurs are birds and once you note that you can’t unsee it.

In a stroke of geological luck in the Late Cretaceous what was once flat beachfront wetland was jacked up at an angle by two tectonic plates sliding under one another called the Laramide Orogeny. This angling gives us some of the most stunning formations in the foothills (think Red Rocks Amphitheatre) but also provides a kind of outdoor exhibit space perfect for humans strolling by to view all its embedded fossils. One of the best hikes around if you’re into ichnology (the study of the fossilized tracks, trails, burrows and excavations made by animals).

It takes a trained eye (which I do not have) to spot some of these tracks. Points to the curators of Dinosaur Ridge for making the good stuff obvious. Here’s a rare Velociraptor track. That hoop is maybe 4″ in diameter, a reminder that true Velociraptors were the size of turkeys (and feathered like them too). Definitely wouldn’t want to tangle with one, but also not the big scaly door handle-operating baddies from the movies.

The Morrison Natural History Museum located near Dinosaur Ridge is a standout. Intimate, chocked with great local fossils and full of helpful one-on-one guides (all of whom are city employees — go off, Morrison!), it is exactly what a museum should be. Being mostly the display and preparation facility for fossils discovered over at Dinosaur Ridge, you get to see the real thing. Not many casts here. Highlights include the story of the discovery of the first Stegosaurus nearby, infant dinosaur tracks surrounded by giant sauropod imprints (how did they not get trampled?), an outdoor dig pit, and pointers to plant survivors of the K-Pg extinction. As you can see from the above video, part of the exhibit space allows you to sit down and try your hand at removing rock matrix from an Apatosaurus skull with a dental drill. If you’ve got good eyesight, a steady hand, and an infinite amount of patience, perhaps fossil preparator is the job for you?

In far northwest Colorado straddling the Utah border is Dinosaur National Monument. I visited in the winter so it was just me and the ranger and several thousand jumbled dinosaur bones. The highlight is certainly the “Wall of Bones” which the park has left in situ and built a lovely enclosure around called the Quarry Exhibit Hall. Like Dinosaur Ridge, it’s tilted at a perfect viewing angle thanks to tectonic subduction. All these bones in one place it is pretty confidently theorized come from an ancient stream that just washed them all into one place. Checking off another box on the things-that-appeal-to-John list is that Dinosaur National Monument is an official International Dark Sky site. There’s no artificial light anywhere. Fossils by day, stargazing by night. I must return. (Zoom into the shirt to see the best gift I have ever been given.)

T-Rex gets all the love, but the earlier Allosaurus was every bit the terrifying carnivore, if slightly smaller. Check out the horns on its brow where evolution apparently decided “death machine but more demonic”.

The Colorado town nearest the national monument and formerly known as Baxter Springs renamed itself Dinosaur in the 1960s and they have not looked back. Pictured is a tyrannosaur wanting nothing to do with the soft touch of a carwash. (The town’s counterpart on the Utah side, Vernal, arguably takes its terrible lizards even more — or less? — seriously. Every other business is festooned with some form of fiberglass saurian.)

See that missing tip of the Diplodocus vertebra she’s pointing to? Paleontologists agree that’s what happens when a giant theropod chooses you for a meal. This attack would have taken out a sizable piece of tail meat (and of course part of a bone), but clearly the Diplodocus lived another day. That is, until it was entombed in the mineral-rich sediment that allowed it to fossilize and be presented at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Bad day for ol’ Diplo, good for us.

Over Grand Junction way the Dinosaur Journey Museum has some striking specimens including a sauropod femur with deep claw marks, properly feathered dinosaur models (which, maybe it was the animatronics, audio, and lighting, but to me floofy dinos are somehow even more chilling than lizardy dinos), and the skull starring in your next nightmare from Diabloceratops. Step back, Allosaurus. Your horns ain’t nothin’. Their working paleo lab, pictured above, was the largest I have seen so far.

So that Western Interior Seaway whose west coast provided such good fossil-making sediment on its shores also delivers up some incredible marine reptiles and pterosaurs, which, while neither are dinosaurs taxonomically, are related contemporaries and just as fascinating. Most of what’s on display at the Dinosaur Resource Center — located a short way into the mountains up from Colorado Springs — was unearthed by the for-profit Triebold Paleontology company who runs the center, a unique business model to say the least.

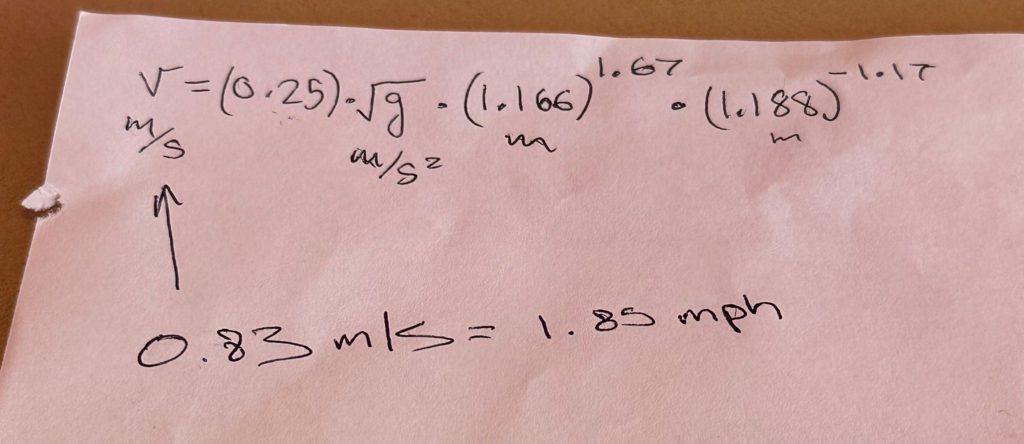

All of this is just dilettante paleontology of course. I don’t even know that I qualify as an enthusiast. Admirer, maybe? Paleontology is so radically cross-disciplinary there are entry points from dozens of domains: geology, biology, botany, the visual arts, math, data science, etc. As an example, my son, a physics nerd, was intrigued by our ability to measure footprint size and stride length to accurately calculate pace — a glimpse into not what the dinosaur was but what it was doing. And that’s just extraordinary.

It’s not all about the science, of course. The idea for Dinger, the mascot of the Colorado Rockies baseball team, hatched during the construction of Coors Field when some dinosaur bone fragments were unearthed. It’s impossible to know if those fossil bits came from a Triceratops, though scientists are fairly certain they come from an herbivore (which the ceratopsians were). Somehow Dinger is bipedal, but we’ll let that slide as he’s one of only two (non-avian) dinosaur mascots in all of professional sports.

I’ve found dinosauriana in the strangest places. An otherwise-average Best Western in a Denver suburb with legit fossil casts, vintage paleontology gear, and weekly lectures? Sure why not. How can you not love its murals depicting the feud between 19th century paleontologists Edward Cope and Othniel Marsh of “bone wars” fame? These fellows would actually sabotage each others’ digs they hated each other so much. Immortalized now on the side of mid-tier hotel chain. Nice work, gents.

It’s all gone now, of course. The actual dinosaurs, that is. Paleontology itself is having a bit of a golden age, if the pace of scientific discovery is any measure. But the mindboggling diversity and longevity of these vertebrate marvels ended 66 million years ago. Yes, with a bang, but also likely with a whimper. One ongoing area of scientific research and debate is just how long it took everything to die after that very bad day off the Yucatán. While there are no dinosaur fossils found above the Iridium Layer, the millimeters of strata that make up its layers are measured in millions of years. It’s possible dinosaurs survived for a while after the impact, but what’s nearly certain is that it was radical changes in climate that ultimately ended their particular ecological niche. (Indeed climate change is the culprit in all our planet’s mass extinctions, including the worst one of all which gave rise to the world the dinosaurs inherited.) Today paleontology is not just digging up scary beast bones or fodder for big screen thrills. It’s proof that our global ecosystem is a fragile one, an eschatology written in mineralized organic remains. Towns become ghosts; seemingly invincible living systems become ghosts. Paleontology isn’t about the past, ultimately; it’s a prediction.

If you’d like to delve further I recommend the Apple TV+ documentary series Prehistoric Planet (two seasons so far), the Terrible Lizards podcast, and a few good books.