Eastbound and down

Some more life news from the summer that keeps throwing curve balls.

After eight wonderful years in Colorado we’re moving cross-country for a career opportunity at Robyn’s company mothership in Connecticut, just a few train stops up from NYC. Not sure where we’ll live exactly. If you know the CT coast, advice is very welcome!

It’s tough to leave this amazing, gorgeous state, but the timing is right for lots of reasons, not least of which is that all the kids are off to college and grad school now. Robyn starts her new role out there Oct. 1. Meanwhile, I’ll orchestrate the largest purgation of stuff we will (hopefully) ever undertake. Home will go on the market shortly after that and we hope to see all our local pals before we scoot.

Eastbound and down, from the mountains to the coast!

The Ghosts of Colorado

The Terror Tourist is my occasional segment on the Heavy Leather Horror Show, a weekly podcast about all things horror out of Salem, Massachusetts. (Segment begins at 12:12, but you’ll enjoy the whole thing!) These segments are also available as an email newsletter. Sign up here, if interested.

Hail and well met, travelers! I am your guide, your troubadour of horror, for The Terror Tourist — an itinerary of dark destinations, a travelogue of dread, a must-see list of ghastly locales worldwide. Each episode we’ll explore a new place — real or imagined, geographical or psychological. With these surveys of the macabre as inspiration I encourage you to strike out and blaze your own trail through the darkness!

Today our journey takes us through the state of Colorado, a rectangle of diverse vertical and horizontal lands in the Mountain West of the United States. While your association between Colorado and horror may begin and end with the music of John Denver, I assure it is so much worse. Let’s go for a hike!

Millions of years before it was known as Colorado this land was covered by a great inland seaway plied by the most terrifying creatures ever to make water their home. Take Xiphactinus, the 24’ long angular death machine the inside of whose serrated maw would be the first you ever saw of it and the last sight of your sorry life. Or the fierce mosasaur, a 50’ long monstrosity whose thirds were essentially giant crocodile, whale, and eel — and which even the largest sharks gave a wide berth. None of these creatures survived the meteor impact of 66 million years ago, you may be grateful to know, but their fossilized skeletons — and teeth, so many shed teeth! — form a rich, literal foundation of terror beneath your hiking boots in this land we now call Colorado.

Mosasaur and Xiphactinus, Dinosaur Resource Center, Woodland Park, CO

You might have noticed the signpost at the trailhead for all the supernatural destinations upcoming. We’ll get there soon enough, but, sadly, there are plenty of waypoints of real life horror I want to note here for your future exploration:

In the 19th century colonizing settlers waged a genocidal campaign against the native inhabitants of the lands here, culminating in the atrocity known today as the Sand Creek Massacre. I will not provide detail except to say 1) This slaughter was actually praised in histories and monuments as an act of near-inevitable nation-building until shockingly recently and 2) The belief in Manifest Destiny has justified more horrific acts than the sum of every movie this podcast has or ever will review. (As an optional detour, I point you to the film Blood Quantum, which centers the Native American experience during a zombie apocalypse. Though set in Canada rather than Colorado it is a most creative reimagining of the concept of an Indian reservation.)

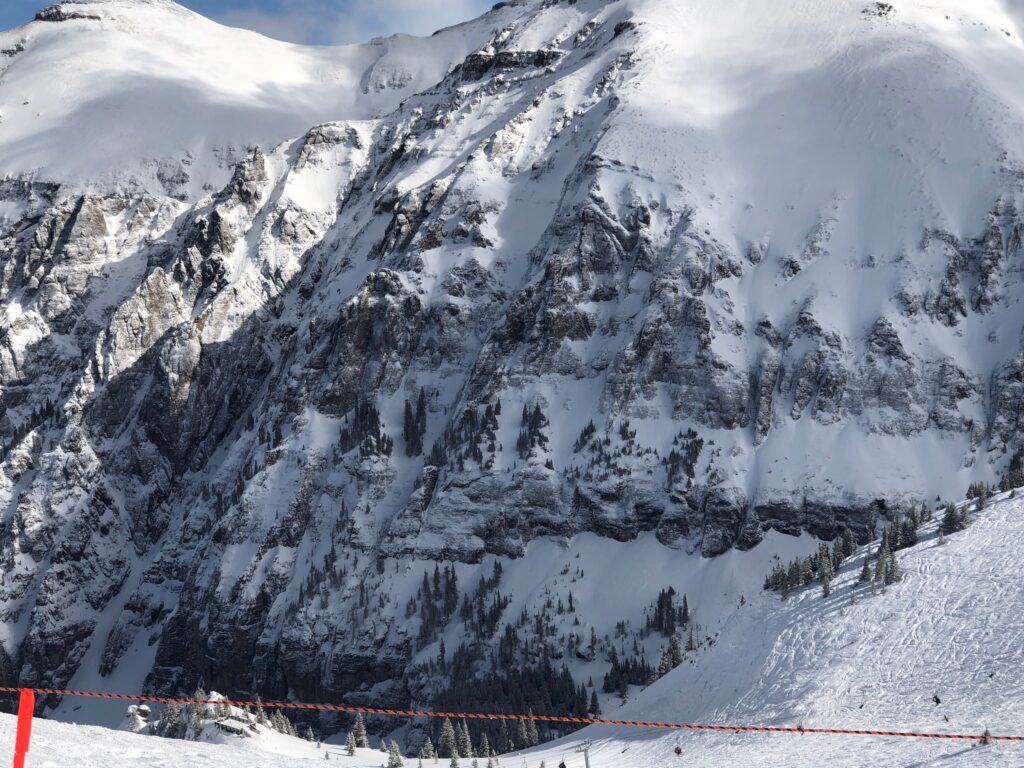

You’re not cold are you? You did dress in layers for this hike, right? See, it’s not just human behavior to fear here. The state itself seems to have it out for you. The most 14,000 foot-plus mountains in the continental US of course delivers brutal cold, blinding snowstorms, avalanches, piercing winds, and deliriously low levels of oxygen at altitude. Oh it’s also super dry, so you’ll dehydrate if all the other things don’t get you first.

The sheer mountain faces of Telluride, Colorado

Did you hear that? That rustling in the underbrush? Don’t panic. Apex predators have mostly been sacrificed at the altar of industrialized agriculture, but we do have bears (no grizzlies though!) and just recently the gray wolf was reintroduced as an experiment in ecological rebalancing. Moose and elk can kill you by sheer size, but they don’t necessarily want to kill you. Actually moose might. The tip here is to walk noisily. Most animals don’t want anything to do with you … unless you sneak up on ‘em and they get startled.

You may think we’re hiking through the middle of nowhere. But a lot of these places were once raucous somewheres. Only to eventually become ghost towns. Hundreds of ghost towns, from piles of rubble barely discernible in the brush to actual towns full of rotting structures seemingly frozen in time, dot the landscape. Of course ghost towns are spooky, full of memory and loss — ready set-pieces for tales of actual ghosts. Surprisingly few films to my knowledge have actually used these locales at least in Colorado.

The ghost town of St. Elmo, Colorado

For me, what’s more interesting to ponder is why these booming burgs went bust. Usually it’s some sort of sudden resource scarcity — like the gold veins went dry, or the silver market crashed — or a technological change — a new rail line bypasses the town or a new road with a better grade makes it easier to get someplace else. The idea of these places grimy with miners, entrepreneurs, charlatans, prostitutes and barkeepers one day — and then nothing virtually overnight is the real scare for me. Our market economy is a cheery midwife and a merciless executioner.

There are two can’t miss destinations coming up before our journey ends.

Let’s walk back in time to the mid 19th century on the outskirts of the booming new city of Denver. About 160 acres of land is set aside as Mount Prospect Cemetery just southeast of the central business district and what would become the state capitol. And just as Denver is swelling with people coming to the Rockies looking for gold, silver, and a new life, the city cemetery is swelling with those who instead found disease, bullets to the head, and death. By 1898 there are about 5,000 bodies in the dirt here, but times are changing in urban design and this is era of the City Beautiful movement where parks, leafy boulevards, and neoclassical design are all the rage in proving that your city is to be taken seriously. So Denver wants to turn the cemetery — no longer on the outskirts of the growing city — into a beautiful new park. Surely you see where this hike is headed, fellow traveler.

Photo: Denver Public Library

The city undertook the task of moving the 5,000 graves, but the effort was bungled from the start. The movers were paid by the coffin so enterprising gravediggers would dismember corpses and shuffle parts into smaller, more numerous child-sized boxes. When the city discovered this, they dismissed the whole crew and admitted they were out of money to move the remaining 2,000 bodies. The city gave family members a few weeks to claim bodies, but as many of these graves were of the indigent and unclaimed victims of crime, few people came forward. So, the park conversion continued, bodies still in the ground. (Sidenote: the segregated far southwest of the cemetery filled with the corpses of Chinese immigrants who came to help build the transcontinental railroad was dutifully disinterred by the small Chinese community here and all bodies shipped back to China.)

Walk with me over here and, if our location and the angle of the sun is right, you can still make out divots in the rolling hills of the park where the graves have ever-so-slightly subsided. Every day, not two blocks from my house people lounge and dogs run about oblivious to the corpses beneath the picnic blankets and volleyball nets. Part of the former cemetery, now called Cheesman Park, was given over to create the Denver Botanic Gardens whose construction expansions over the years continue to unearth graves and corpses — most recently in 2022. Ghost stories in this park, unsurprisingly, are plentiful. I’m willing to believe.

Photo: Denver Post, “Four preserved skeletons unearthed at Denver’s Cheesman Park, once a cemetery“, 2010

There’s an unsubstantiated rumor that the unmoved graves and subsequent development of this park was an inspiration for Poltergeist. Who knows? What is substantiated is the story behind the 1980 film The Changeling, which takes place in a mansion that directly sat on Cheesman Park. Starring George C. Scott trying his hardest not to be irascible, this classic haunted house film was inspired by a story written by a composer named Russell Hunter who was renting the Henry Treat Rogers House in 1968. His recounting is nearly identical to the story in the film: bouncing balls in hallways, a sealed-over door leading to a hidden room, the discovery of a diary from a person locked away from public view, a psychic medium, and ultimately the revelation of the child-swap. The Denver Public Library has tried to verify any part of this tale — to no avail. But it made its way to film and a great one at that! The mansion was demolished in the 70s for a sad high-rise condominium building. Poltergeist and The Changeling — this park has something for everyone, I tell you!

The final stop on our hike brings us to the unavoidable importance of Colorado to Stephen King’s and Stanley Kubrick’s very separate masterpieces called The Shining. Up in the mountains here in a small town called Estes Park is a gorgeous old hotel called The Stanley. Originally created as a retreat for wealthy Easterners suffering tuberculosis and other ailments, the hotel eventually became a high-end stopover for tourists on their way to Rocky Mountain National Park, established in 1915. Given the massive amounts of snow at elevation the hotel was only open in the summer months (until 1983). But back in 1974 the author Stephen King, coincidentally, happened to book a room at the Stanley the day before it was being shuttered for the winter. He roamed the halls of the near-desolate hotel, had a drink at the bar with a bartender named Grady, and spent the night in room 217. The rest is mostly history, though of note to those who know the sizable differences between the book and the film, The Stanley did actually partially explode in 1911 due to a gas build-up. Clearly King learned this during his stay, providing him with the novel’s conclusion.

The Stanley Hotel, Estes Park, Colorado

The hotel itself is in no way scary. I’ve stayed there several times and it is just a beautiful, Federalist-style set of buildings that seem more at home on the east coast than the mountain west. If you’ve seen the terrible 1997 miniseries of The Shining directed by King (or the 1994 film Dumb and Dumber) then you have seen The Stanley. No hedge row labyrinth, no art deco ballroom, really nothing but the original bar that evokes dread. For decades the ownership of the hotel shied away from its associations with the book and film, especially since none of the latter was filmed there. But eventually they came to embrace the notoriety, planting their own very short hedge maze, offering Shining tours, and even now throwing an annual Shining Ball (which my wife and I have attended). But hotel management is all in now: in a partnership with the horror film production company Blumhouse the hotel is building out a 80,000 square foot film center and museum devoted to horror cinema. It should be open in a few years. I want to work there.

As for the other Stanley, Kubrick, he didn’t have much use for Colorado in his film. Not only was it not filmed here but even the one location-specific reference in the film — the story of the Donner Party that Jack recounts to his family on the ride up to the hotel — takes place in California. There’s a brief establishing shot outside the Torrance’s Boulder apartment — still there looking the same right next to the University of Colorado — but that’s it!

As terror tourists, however, you will likely care to know that Kubrick did use much of the mountain west as inspiration. He cribbed the design of the lobby and Native American iconography from the Ahwahnee Hotel in Yosemite National Park in California (for real, like down to the location of individual light fixtures), gathered exterior shots from the Timberline Lodge atop Mount Hood in Oregon, filmed the opening title sequence at Going-To-The-Sun Road in Montana’s Glacier National Park, and maybe even stole the red bathroom from the Biltmore Hotel outside Scottsdale in Arizona. That said, 98% of the film was shot on a soundstage at Elstree Studios north of London.

This is where I leave you to hike on your own, listeners. There are plenty of other sights for you to explore of course. I’ll note the excellent The Black Phone from 2021, set in 1970s Denver, the Day of the Dead remake from 2008 which isn’t awful, and the unrated Snowbeast from 1977 set in Crested Butte, Colorado. This film is awful in the very best way possible. I highly recommend it.

Good luck on your travels. Remember to hydrate and stay wary!

A full list of the movies mentioned above can be found at Letterboxd. Find out where to watch there.

Ghost Ecosystems

I teach a course at CU Denver on urban technologies where, to the bewilderment of most students, we begin by studying a decrepit urban typology somewhat unique to the American West: ghost towns. Where students are expecting robot cars and sparkling sci-fi skylines they get depopulated ruins and crumbling foundations. It takes several sessions before students appreciate why we start this way. The afterlife of towns and cities exposes quite a bit about why they were created, what assumptions they were built upon, and what larger systems they are enmeshed in. If these towns are ghosts, how exactly did they die?

Apart from their educational value, ghost towns in the western US are uniquely fun to explore, little open-air museums of urban decay which defy assimilation into newer development as happens in the east. And it’s not just towns: ghost infrastructure is everywhere, like the time-smoothed scar tissue of historic Route 66 reminding how we stitched together the country west of Chicago in the early 20th century.

More personally, as a relative newcomer to Colorado from the midwest I’ve come to love ghost towns simply for the excuse they provide to explore the region I now call home. Placemaking by way of un-places.

So it seems somewhat obvious in hindsight that I’d inevitably be drawn to dinosaurs, an even more complex and further bygone ecosystem whose presence in the American West is as iconic as tumbleweeds and spurs. Dinosaurs may seem like quite a conceptual leap from ghost towns. But both are sometimes barely visible threads woven into the fabric of our landscapes here, simultaneously a record of engagement with, modification of, and sometimes defeat by the environment itself. This interplay between environment and the creatures that lived in it — indeed were ultimately ended by it — I think accounts for its hold on me, someone with zero paleontology or geology (and very little biology) background. How could an ecosystem as complex as that of the Age of Reptiles, lasting hundreds of millions of years through several extinction events, simply end? Indeed, did it really end? (Hello, birds!) Like ghost towns, the dinosaurs that once prowled (and flew and swam) here have been remade into a kind of modern brand. From gas station logos to baseball team mascots to entire town identities these “terrible lizards” seem endlessly repurposeable.

My first descent into this mild mania actually began not in Colorado but where it all ended off the coast of the Yucatán peninsula.

Vacationing there last year naturally I had to educate myself on the cataclysm of the bolide impact 66 million years ago which brought an end to (almost) all dinosaurs. Once I felt I knew enough I then put together a small lecture, to the chagrin of my family and friends who just wanted beachside rest and relaxation. But that impact! Obviously everything in our locale was obliterated, instantly pulverized, but it was the thought of what the world became in the years and decades after the fiery hellstorm that really got me thinking. A world choked by carbon and airborne particulates, sunless, scorched from heat coming in from the sun but having no way to radiate back out.

How a geologist named Walter Alvarez enlisted his physicist father Luis to figure out just why the boundary in rock sediment separating the Cretaceous period (lots of dinosaur fossils) from the Paleogene period (nary a dinosaur fossil) has levels of the element Iridium 100 times higher than naturally occuring is a story worth reading. Ultimately this layer, called the K-T or K-Pg boundary, and which can be found nearly everywhere on our planet, is the blanket of asteroid material that fell back to Earth after its immolation off the Yucatán — a burial shroud placed gently (and permanently) in the geologic record eulogizing almost 75% of all species at the time.

This was all good fun … until I decided to make a solo mountain bike day trip to Picket Wire Canyonlands in southwest Colorado last year. The trek about killed me — hot, dry, arduous biking on sandy trails. Also I didn’t bring enough water. On the other hand, I had the entire 16.7 trail route to myself, seeing not another soul the whole day. This solitary experience became all the more magical when I arrived at my destination, the largest dinosaur tracksite in North America. 150 million years ago plant-chomping Apatosaurus and flesh-ripping Allosaurus squished their feet into the soft lakeshore here which silted over and hardened into over 1,300 tracks in at least 100 separate paths criss-crossing every which way. I dismounted my bike right in the middle of it all, sat on the sun-baked rock, reveled in a total lack of cell signal, and tried to imagine what the place would have looked like — sounded like, smelled like! — as the herds slopped through.

And then I was hooked. How could I not learn more at this point? I had placed my foot inside the footprint of another living creature from the Jurassic period out on a bike ride just a few hours from my home.

Sure, Sue the T-Rex was found in South Dakota. Montana has the infamous Hell Creek Formation. Utah gave us the raptor that successfully retconned Spielberg’s originally ludicrous depiction of Velociraptors in Jurassic Park. Even Kansas can flaunt its one-time Western Interior Seaway and basically all the great marine reptile and pterosaur specimens.

But Colorado is the state that I think most fulsomely embraces its dinosaur history. Here are some highlights.

The Triceratops Trail (officially the Parfet Prehistoric Preserve) on the edge of Golden offers an easy walk through former clay mining trenches that have exposed all kinds of interesting dinosaur tracks. Triceratops is confirmed with possible Tyrannosaurus and Edmontosaurus. Easily as interesting are trace fossils of birds, small mammals, beetles, palm fronds, and even (arguably) raindrops. The site abuts an active golf course. It’s a bit jarring to see humans frolicking around the perfectly engineered invasive species of putting green grass, then turning around to face a 100+ million year old wall of dinosaur tracks. I wonder which will outlast the other?

A lizard basks on the Triceratops Trail separated from its clade-mates by a mere 231 million years (evolutionarily). 19th century depictions of dinosaurs took a lot of inspiration from their lizard cousins. We know now that there was very little tail-dragging and tongue-flicking. Our modern dinosaurs are birds and once you note that you can’t unsee it.

In a stroke of geological luck in the Late Cretaceous what was once flat beachfront wetland was jacked up at an angle by two tectonic plates sliding under one another called the Laramide Orogeny. This angling gives us some of the most stunning formations in the foothills (think Red Rocks Amphitheatre) but also provides a kind of outdoor exhibit space perfect for humans strolling by to view all its embedded fossils. One of the best hikes around if you’re into ichnology (the study of the fossilized tracks, trails, burrows and excavations made by animals).

It takes a trained eye (which I do not have) to spot some of these tracks. Points to the curators of Dinosaur Ridge for making the good stuff obvious. Here’s a rare Velociraptor track. That hoop is maybe 4″ in diameter, a reminder that true Velociraptors were the size of turkeys (and feathered like them too). Definitely wouldn’t want to tangle with one, but also not the big scaly door handle-operating baddies from the movies.

The Morrison Natural History Museum located near Dinosaur Ridge is a standout. Intimate, chocked with great local fossils and full of helpful one-on-one guides (all of whom are city employees — go off, Morrison!), it is exactly what a museum should be. Being mostly the display and preparation facility for fossils discovered over at Dinosaur Ridge, you get to see the real thing. Not many casts here. Highlights include the story of the discovery of the first Stegosaurus nearby, infant dinosaur tracks surrounded by giant sauropod imprints (how did they not get trampled?), an outdoor dig pit, and pointers to plant survivors of the K-Pg extinction. As you can see from the above video, part of the exhibit space allows you to sit down and try your hand at removing rock matrix from an Apatosaurus skull with a dental drill. If you’ve got good eyesight, a steady hand, and an infinite amount of patience, perhaps fossil preparator is the job for you?

In far northwest Colorado straddling the Utah border is Dinosaur National Monument. I visited in the winter so it was just me and the ranger and several thousand jumbled dinosaur bones. The highlight is certainly the “Wall of Bones” which the park has left in situ and built a lovely enclosure around called the Quarry Exhibit Hall. Like Dinosaur Ridge, it’s tilted at a perfect viewing angle thanks to tectonic subduction. All these bones in one place it is pretty confidently theorized come from an ancient stream that just washed them all into one place. Checking off another box on the things-that-appeal-to-John list is that Dinosaur National Monument is an official International Dark Sky site. There’s no artificial light anywhere. Fossils by day, stargazing by night. I must return. (Zoom into the shirt to see the best gift I have ever been given.)

T-Rex gets all the love, but the earlier Allosaurus was every bit the terrifying carnivore, if slightly smaller. Check out the horns on its brow where evolution apparently decided “death machine but more demonic”.

The Colorado town nearest the national monument and formerly known as Baxter Springs renamed itself Dinosaur in the 1960s and they have not looked back. Pictured is a tyrannosaur wanting nothing to do with the soft touch of a carwash. (The town’s counterpart on the Utah side, Vernal, arguably takes its terrible lizards even more — or less? — seriously. Every other business is festooned with some form of fiberglass saurian.)

See that missing tip of the Diplodocus vertebra she’s pointing to? Paleontologists agree that’s what happens when a giant theropod chooses you for a meal. This attack would have taken out a sizable piece of tail meat (and of course part of a bone), but clearly the Diplodocus lived another day. That is, until it was entombed in the mineral-rich sediment that allowed it to fossilize and be presented at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Bad day for ol’ Diplo, good for us.

Over Grand Junction way the Dinosaur Journey Museum has some striking specimens including a sauropod femur with deep claw marks, properly feathered dinosaur models (which, maybe it was the animatronics, audio, and lighting, but to me floofy dinos are somehow even more chilling than lizardy dinos), and the skull starring in your next nightmare from Diabloceratops. Step back, Allosaurus. Your horns ain’t nothin’. Their working paleo lab, pictured above, was the largest I have seen so far.

So that Western Interior Seaway whose west coast provided such good fossil-making sediment on its shores also delivers up some incredible marine reptiles and pterosaurs, which, while neither are dinosaurs taxonomically, are related contemporaries and just as fascinating. Most of what’s on display at the Dinosaur Resource Center — located a short way into the mountains up from Colorado Springs — was unearthed by the for-profit Triebold Paleontology company who runs the center, a unique business model to say the least.

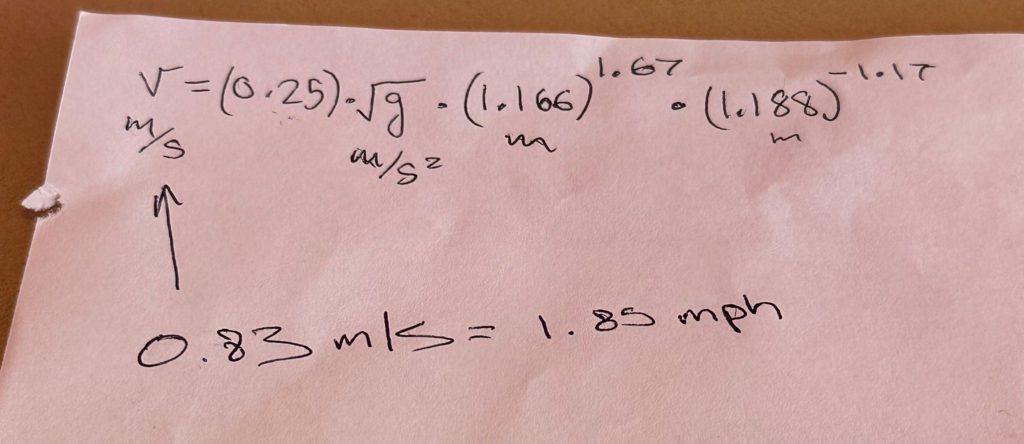

All of this is just dilettante paleontology of course. I don’t even know that I qualify as an enthusiast. Admirer, maybe? Paleontology is so radically cross-disciplinary there are entry points from dozens of domains: geology, biology, botany, the visual arts, math, data science, etc. As an example, my son, a physics nerd, was intrigued by our ability to measure footprint size and stride length to accurately calculate pace — a glimpse into not what the dinosaur was but what it was doing. And that’s just extraordinary.

It’s not all about the science, of course. The idea for Dinger, the mascot of the Colorado Rockies baseball team, hatched during the construction of Coors Field when some dinosaur bone fragments were unearthed. It’s impossible to know if those fossil bits came from a Triceratops, though scientists are fairly certain they come from an herbivore (which the ceratopsians were). Somehow Dinger is bipedal, but we’ll let that slide as he’s one of only two (non-avian) dinosaur mascots in all of professional sports.

I’ve found dinosauriana in the strangest places. An otherwise-average Best Western in a Denver suburb with legit fossil casts, vintage paleontology gear, and weekly lectures? Sure why not. How can you not love its murals depicting the feud between 19th century paleontologists Edward Cope and Othniel Marsh of “bone wars” fame? These fellows would actually sabotage each others’ digs they hated each other so much. Immortalized now on the side of mid-tier hotel chain. Nice work, gents.

It’s all gone now, of course. The actual dinosaurs, that is. Paleontology itself is having a bit of a golden age, if the pace of scientific discovery is any measure. But the mindboggling diversity and longevity of these vertebrate marvels ended 66 million years ago. Yes, with a bang, but also likely with a whimper. One ongoing area of scientific research and debate is just how long it took everything to die after that very bad day off the Yucatán. While there are no dinosaur fossils found above the Iridium Layer, the millimeters of strata that make up its layers are measured in millions of years. It’s possible dinosaurs survived for a while after the impact, but what’s nearly certain is that it was radical changes in climate that ultimately ended their particular ecological niche. (Indeed climate change is the culprit in all our planet’s mass extinctions, including the worst one of all which gave rise to the world the dinosaurs inherited.) Today paleontology is not just digging up scary beast bones or fodder for big screen thrills. It’s proof that our global ecosystem is a fragile one, an eschatology written in mineralized organic remains. Towns become ghosts; seemingly invincible living systems become ghosts. Paleontology isn’t about the past, ultimately; it’s a prediction.

If you’d like to delve further I recommend the Apple TV+ documentary series Prehistoric Planet (two seasons so far), the Terrible Lizards podcast, and a few good books.

Walking the networks of Denver

Cross-posted at Medium.

Years ago, when I was just moving into the world of urban technology, I stumbled upon the urban “walkshop” format developed by Adam Greenfield and Nurri Kim (refined and expanded by Mayo Nissen). These walking tours were collaborative, lightly-structured investigations of surveillance and communications machinery sprinkled throughout various cities. Though these walkshops pre-dated what some now call the Internet of Things, there was plenty to look at, especially as cameras trained on the public way proliferated.

Sometime later I helped curate the City of Big Data exhibit at the Chicago Architecture Foundation. Being primarily a touring organization, CAF staged a few walking explorations of the collection, transport, and effects of data throughout the city. I was not involved in the development of this tour, though the idea of an “architecture” tour that took as its subject the hiding-in-plain sight constellation of objects, poles, wires, sensors, and cameras that shape a city’s daily life was never far from my mind.

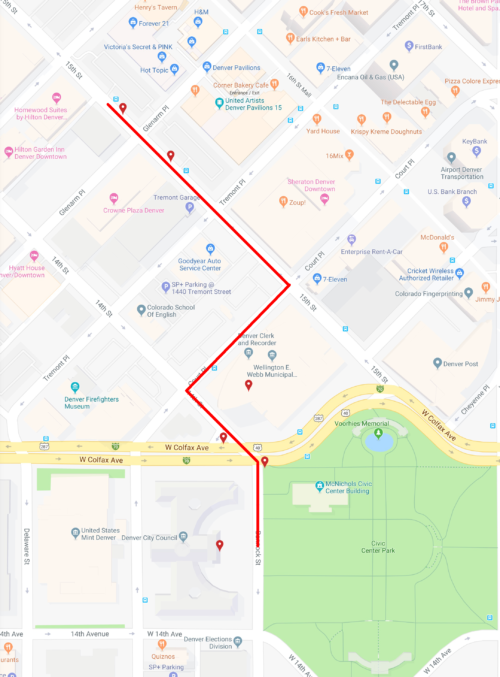

And so it was that yesterday I led a tour of about 20 people during the Denver Architecture Foundation’s Doors Open Denver, our city’s annual two-day invitation to explore architecture and spaces normally off-limits to the general public. Called Networks of Denver: Evolution of a Smart City, the tour was obviously an outgrowth of my work with CityFi. Less obvious – at least to the folks who took the tour, I hope – is that I still feel like a newcomer to Denver; my naïveté about how things work here still feels like license to be aggressively curious. So we set out for 75 minutes to find evidence of digital technology in our physical, urban surroundings.

Why do this? Who cares about unseen boxes and invisible wireless fields? The easy answer to the second question is: a surprising number of folks, with varied backgrounds, most of whom had participated in other, more traditional architecture tours during the weekend. (I suspect we could have filled another tour had I offered it twice.)

Back to the why: my sense is that as more and more urban technology crowds onto our streets it has become increasingly difficult to miss. A few years ago you might never have noticed distributed cellular antennas festooning decaying rooftop water tanks, but today the streetscape is cluttered with many more devices much closer to the sidewalk and roadway. Add to that an increasing awareness amongst the general public that technology is changing the way we use cities: red light cameras flash in our faces leaving us to wonder if we’re driving the car it caught; dockless scooters zip us around then lay in ugly piles on curbs; pay-by-cell options mean never having to run out to feed the meter.

This networked machinery shapes our urban lives. Like brick-and-mortar architecture, the shaping is subtle, often unrealized consciously. Maybe we were given more time to transit the crosswalk because an elderly man was slowly crossing opposite us and a pedestrian video analytics system gave him more time to make it. Maybe you don’t want to picnic in the park because you know the LTE connection there is spotty. Maybe an environmental sensor whose video array is pointed straight up at the sky has informed your hyperlocal weather app which advises you to jump on the bus rather than walk because it knows your few blocks are about to get a sunshower.

With the able assistance of Emily Silverman and Mike Finochio from the City and County of Denver, we were able to look at some things truly inaccessible to the public, including the inside of a traffic signal control cabinet and the city’s traffic management command center. The latter was especially interesting since it is the main terminus of the information being generated from many of the technologies we saw in the field. These included, but were not limited to:

- traffic signal phase and timing controllers

- signal malfunction monitoring units

- two different models of vehicle-to-infrastructure radios (DSRC)

- pan-tilt-zoom traffic cameras

- parking analytics cameras

- pedestrian video analytics cameras

- video and bluetooth-based queue sensors

- emergency vehicle pre-emption radios

- crosswalk analytics sensors

- LTE-enabled parking meters

- WiFi mesh public safety surveillance cameras (“HALO”)

- pavement boxes (electric + fiber)

- distributed antenna systems for cellular (LTE)

- ambient light sensors on street lights

- public electric, dockless scooters

- public docked and dockless bikes

- surveillance cameras on private property

Our discussion of the potential ways that augmented reality could affect the urban realm, for good and for ill, was greatly aided by a five-year-old art/information installation along 14th Street, one of the main corridors we explored. Called the 14th Street Overlay this project has installed antique-looking optical instruments and QR code-enabled placards along the street that attempt to superimpose historical images in situ. How will we behave on sidewalks when we can call up these images on our own devices registered and overlain seemlessly on the physical world? How will that change our sense of place?

We ended our tour looking at two newer and larger installations: a Verizon 5G pole and an information (er, “transit amenity”) kiosk. The thick, towering 5G pole and the number of them required by Verizon and their competitors to blanket the city have lately been a source of some public concern. There was much discussion about the city’s role in making sure such infrastructure blends in to the built environment, either by combining their radios into existing street furniture or requiring that multiple carriers share a common host.

The kiosk was a bit of a disappointment as it is clearly a giant piece of outdoor advertising first, “amenity” second. The public transit information offered is static (i.e., a schedule rather than real-time tracking) and non-interactive. And yet the unit takes up an enormous amount of space on the sidewalk. Apparently most of the inside of the monolith is empty. Most agreed this was a wasted opportunity to do something truly useful in our public way.

I consider the day a success, as I do the version of the tour I gave to my CU grad student class the evening before. Many of the topics that our exploration prompted were about issues of public versus private control and data (observability versus surveillance), how such instrumented intersections could lead to a real-time urban design, ethical concerns about what happens during the transition phase from unconnected to connected vehicles (“is it wrong to provide information to a subset of motorists?”), and how far the city should go to help the private sector test their wares.

This was only the beginning of the conversation. It’s difficult to unsee all this machinery once you know where it is and what it does. I encourage you to go exploring in your city.

If you’re interested in diving deeper into the world of rarely-noticed technologies that shape our cities, I recommend exploring the work of

Ingrid Burrington, Dan Hill, and, Shannon Mattern (including of course Greenfield and Nissen, linked above).

Our state-spanning urban skyline is not made of steel and glass

Cross-posted at Medium.

CityFi partners John Tolva and Story Bellows frequently find themselves on the frontier of urban change. Their facilitation of major projects often convenes public-private stakeholders, utilizes new models of technology and innovation, and drives policy development, all with the goal of making our cities more livable, vibrant and economically competitive. Currently, this mission extends itself to the western frontier of Colorado. These days, the booming Denver-metropolitan region has largely kicked its historical image as that of a dusty cow town; in fact, two of CityFi’s major Colorado-based projects illustrate the innovative, multi-sector and often regional collaborative momentum this state has built toward creating sustainable, positive change for its diverse communities.

The history of CityFi coincides with the beginning of its relationship with the Denver South Economic Development Partnership (Denver South EDP); it was the project to develop a blueprint for turning the Denver South region — a conglomeration of several small cities driven by its economic hub in the Denver Technological Center — into a 21st Century Innovation District, which was the firm’s first. The Blueprint is a critical component to retrofitting this region — a major economic driver for the state, contributing nearly 20 percent of the state’s economic output — so as to keep pace with the urban changes that Denver is undergoing. Denver South is primarily centered around the major artery of Interstate 25, which runs north-south into the heart of downtown Denver. A new study recently projected that in the next ten years, 70,000 additional people would be coming to the region each day to work, highlighting the critical nature and urgency of determining how infrastructure, local culture and the built environment could be transformed to meet these needs in coming years.

As a result, “the blueprint reinvents the approach to making an effective and attractive suburban landscape by providing a guide for city officials and developers as to how to integrate new technology solutions, approaches to policy and governance, improved land use and cultural change,” Bellows said.

For Denver South EDP, this shift is important to maintaining business vitality in the area, as without addressing these barriers, the region risks losing business to other parts of the city, or even other states. The blueprint also leverages one of the most significant investments made in Denver South in recent decades, that of RTD’s transit infrastructure, including a light rail system, which stretches as far southeast as the City of Lone Tree. CityFi wants to better integrate this asset into the built environment to improve Denver South as a place that can accommodate increased people and their desire to live, work and play within proximity.

CityFi sees the challenge of Denver South as also its greatest opportunity. While Denver South may not have the caché or national intrigue of Denver’s downtown core, CityFi recognizes its fundamental importance as part of Denver’s economic engine, and believes formulating its successful future can inform the efforts of other cities also recognizing the benefit of retrofitting aspects of suburbia to accommodate population growth, mobility patterns and new models of the workplace. In short, CityFi sees opportunity to improve development, asset use, business decision-making and policy in Denver South to not only make the region sustainable, but also to improve the quality of life for those that live and/or work in the area. “Citizens everywhere — not just those in the densest, most active parts of a city — deserve the chance to feel truly invested in and love where they live,” Tolva said.

One of Colorado’s particular strengths, including within the Denver South region, is its propensity toward multi-sector and multi-jurisdictional collaboration. This unique asset is significant when considering the scope of retrofitting suburban regions for the future. Rather than decisions made in siloed vacuums, urban change leaders — from city officials and developers, to business leaders and citizens — can collectively work to shape the development of our cities. “Not only does this approach build capacity, it allows problems to be comprehensively addressed so that the resiliency to weather change is strengthened,” Bellows said. This collaborative approach will help to overcome Denver South’s challenges, including defying the misperception that growth and density leads to a lower quality of life for its citizens. Rather, CityFi seeks to reframe this by educating on how population growth and changes to the built environment will actually provide, not take away from, increased choice and connectivity. CityFi and Denver South EDP believe this will become evident as the blueprint is incorporated into future planning practices, and holds the potential to become a national model for how to approach suburban retrofit that accommodate the needs of both old and new residents and workforce.

CityFi’s other major project with Denver South EDP is the ongoing creation of the Colorado Smart Cities Alliance, which capitalizes on CityFi principles of using innovation and technology to solve the complex urban challenges our cities face. The Alliance — while still nimble and in its early stages — serves as an incubator for Smart City pilot projects, living civic labs, resource and best-practice sharing, and multi-sector and jurisdiction engagement around city challenges that cannot necessarily be addressed through traditional government or private sector avenues.

What is most unique about the Alliance, and what is also evident in the Denver South Blueprint, is the additional leverage that regional collaboration and problem-solving bring to the table. While the Alliance originally began under the auspice of Denver South EDP and the cities it represents, it was quickly realized that this effort would increase in value and return on investment for Colorado citizens if it became a statewide project in which all major cities were engaged. While Colorado cities vary greatly — from small mountain towns, to the Western Slope, to the major cities of the I-25 corridor along the Front Range — what is evident is that each of these cities are facing challenges while adapting to rapidly-changing environments, whether urban, rural or suburban.

As the Alliance unfolds, it will have two main roles: first, to solve city problems where solutions do not currently exist through traditional procurement channels; in essence, as Tolva says, “to loosen the innovation throttle inside of cities, and reduce the risk associated with implementing innovation in government structures.” The other main objective will be for cities to be able to capitalize on the economic development opportunities that arise from the resulting multi-city, cross-sector collaboration. As the Alliance incorporates private sector partners, there is a reciprocal return on investment in being able to test new technologies across a variety of city landscapes to understand the true costs and benefits of their application. CityFi’s role is critical in managing the balance between these public and private participants, while recognizing that both parties are necessary to shape the direction of Smart City solutions and provide a pathway for two-way learning.

As is core to its mission, CityFi advises widening the proverbial doors of the Alliance to involve these cities’ citizens in the process. “Too often in Smart City conversations, there are no citizens present. It’s on us to frame the discovery of city challenges in terms of those they affect — business owners, citizens and workforce. That is ultimately the defining philosophy of CityFi,” Tolva said. “Skepticism about Smart City initiatives arises because they are not centered around the citizen experience.”

CityFi’s excitement around its work with the Alliance is palatable; Bellows and Tolva both acknowledge that while many cities have attempted to pull off a similar structure alone, the Alliance is a national trailblazer in terms of conducting these efforts on a regional or state level. In that spirit, Tolva said, “we are less interested in the jurisdictional boundaries than we are in the experience of these places.”

CityFi’s presence in Colorado continues to grow, and is currently working with Denver Mobility Choice, the City of Aspen, and Panasonic on new urban change projects. The Colorado-based CityFi team has also doubled in the past month with the hiring of a new associate. Look for more updates about CityFi’s Colorado projects in upcoming months.