Supertramp on the brain

I just realized I love Supertramp and always have. WTF. What else do Ilove that I don’t know that I do?

— John Tolva (@Immerito) March 21, 2012

Really the only way to get this out of my head was to mess with it.

Done.

The Brick Brothers

Almost exactly a year ago my sons asked me what “investing” was. A strange question from a 9- and 7-year-old, but I was impressed by the curiosity and it seemed timely given the banking implosion.

I lost the boys midway between arcane regulation and exotic financial instruments, but they were intrigued with the idea of a business more complex than a lemonade stand. And then they wouldn’t shut up about starting one, embarking on an entrepreneurial brainstorming session whose intensity would have made a venture capitalist smile. (Or back away slowly.)

The idea, fairly speedily arrived at, was to build on something the kids had been staring at all their lives. In the days following the birth of each of the three kids I built grayscale mosaics of their birth photos out of 1×1 LEGO bricks. They’ve hung on the wall ever since. The business idea, quite simply, was to build these mosaics for others.

And so was born The Brick Brothers.

Marketing ideas are modeled first in bricks, naturally

Listen up, folks. Here’s where I divulge trade secrets.

We built the site on the superb Shopify platform. It accepts photos uploaded from customers who purchase a completed mosaic or just the raw materials.

We then use an open source application call PicToBrick to generate a number of gridded (48×48), reduced-color images. The image that comes closest to capturing the essence of the original photo is chosen and printed out as a guide for the assembly.

Then the boys snap the pieces onto the baseplate, following what is essentially a color-by-numbers schematic. Dangerously, this is mind-numbing (and finger-numbing) but also requires attention to detail: if you pop the wrong brick in place and only notice it several rows later it’s a huge effort to remove the studs. What makes this a less-than-rare occurrence is that you really only get a sense of the overall image by moving away from it. When you’re up close snapping away it is often impossible to notice an error.

The whole effort takes about 4-6 hours depending on distraction. Then we package up and ship out.

One hurdle — aside from child labor laws — has been finding the 1×1 bricks in bulk cheaply enough. LEGO doesn’t sell in bulk to mere mortals and those bins at their stores contain very specialized bricks. Luckily there’s a massive ecosystem of LEGO re-sellers online, centered on a marketplace called BrickLink. But there’s no single supplier. It’s a scramble to stay well-inventoried and not break the bank.

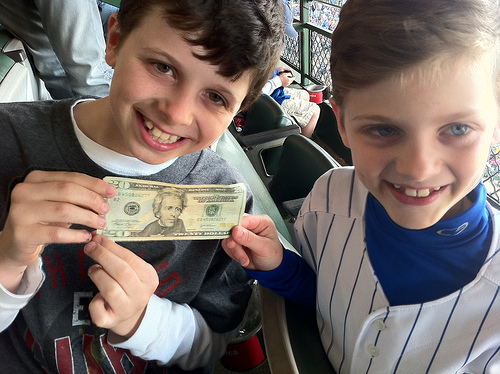

The boys' first investment in The Brick Brothers (from relative strangers at a Cubs game), July 24, 2011

It should be obvious we’re not in this little enterprise for profit, but I’d continue the business with the boys even at a financial loss given its many lessons: time-management, expenses vs. revenue, the importance of marketing, the concept of chiaroscuro, how easy it is to be driven insane by tiny LEGO blocks, etc. We’re having fun and not losing money. Can’t ask for much more than that.

Follow along via Twitter here.

Shovel Ready

Heading into winter late last year we were told that it was going to be one for the record books. And so it has been. Temperatures have yet to go into minus territory and there are towns in Texas with more snowfall than we’ve had. It’s downright bizarre.

But I’m a believer in meteorological karma. Sure, we’re trending way behind average snowfall to date. But that doesn’t mean Old Man Winter can’t go for a late game Hail Mary. I’ll put away the shovel in June.

That’s basically the philosophy of preparedness behind a slew of winter-focused applications created by the City of Chicago over the last weeks at chicagoshovels.org.

It’s all about scales of sharing, really. Last year’s blizzard showed a side of our city rarely talked about: authentic neighborliness. Chicagoans came to each others’ aid, made friends on stranded public transit, and generally bonded in the face of potential calamity. The idea behind Chicago Shovels is to facilitate this latent drive to be good neighbors, to offer tools for sharing in the common experience of a heavy snowfall.

The sharing extends to the code itself. Civic-minded volunteers came together to build parts of Chicago Shovels and some of the code itself was shared via a Code for America-developed project in Boston. And, of course, we’re sharing what we’ve built on our Github account. Cross-municipality, open source development is the way forward.

Many different threads of Mayor Emanuel’s technology mandate are bound together in Chicago Shovels.

Plow Tracker, the first app to launch and certainly the most popular, is a good case study in open data for transparency and accountability. While I talk a lot about open data as a driver of economic development and as analytics fodder, the lesson from Plow Tracker’s launch — and the record-shattering traffic it drove to the city’s website — is that we shouldn’t forget that the ability to peer into the workings of government is the first and possibly most important function of open data.

The Tracker is a good illustration of our open data initiatives: more information is always better than less. If there are patterns to be found, they will be. And no matter what they are, such analysis leads to a more efficient city government.

Plow Tracker is only on during storms, of course. It shows where plows are in real-time with a bit of information as to the city “asset” you are looking at. This is normally salt-spreading plows, but in bigger snow events can include garbage trucks with “quick-hitch” plows attached and even other city vehicles outfitted to plow. As Chicagoist pointed out, watching the map can remind you of a certain popular video game from the 1980’s.

Feedback from the public, coverage in the press, and inquiries from other cities has been overwhelmingly positive. Many have asked for increased functionality, such as a visualization of what streets are cleared. This is tough, as we do not have real-time data on the status of city streets, except what can be visually inspected via cameras and the plow drivers themselves.

Undaunted, the team at Open City took the Plow Tracker data and created Clear Streets. Where Plow Tracker shows where the plows are, Clear Streets shows you where they have been. (If we’re keeping with the gaming analogies, this is to Etch-a-Sketch what the Tracker is to Pac-Man.)

Clear Streets is obviously useful and a great example of the ecosystem of civic developers that are growing on the periphery of government thanks to open data. And with Chicago’s digital startups reaching critical mass and real attention from venture firms, the city is doing its part in nurturing “civic startups” like Open City. (Here’s a clip of the Open City crew and me discussing all this on WTTW’s Chicago Tonight.)

A last note on (and lesson from) the Tracker: context is key. The little text blurb above the map is really crucial to understanding what you are looking at. As an example, sometimes plows are deployed before it starts snowing for preemptive salting of bridge decks. If you did not have this information it would be difficult to rationalize the placement of plows. It’s a lesson for open data in general. The more data, especially real-time data, the more context matters.

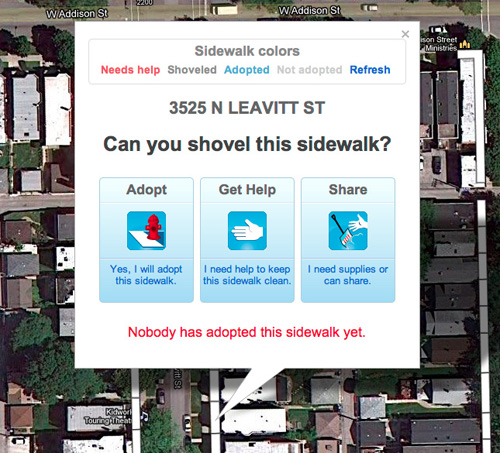

Adopt-a-Sidewalk

The site’s most recently launched app, Adopt-a-Sidewalk, represents the original idea for Chicago Shovels.

Last fall, as Chicago was preparing to become a 2012 Code for America city, we learned about a side project from the Code fellows in Boston. Early in 2011 they had arrived to work on a project with Boston schools but were met with a blizzard. So they built Adopt-a-Hydrant. This idea was to encourage residents to “claim” fire hydrants for shoveling out during the winter. Simple, smart, the right thing to do. And the code was open source.

So we took it with the idea of creating something similar but focused on the public way. We thought we could go a bit bigger than hydrants. See, the Chicago Municipal Code requires residents and businesses to shovel the sidewalk in front of their property. So why not allow them to claim it or claim someone else’s — or ask for help? Claim a parcel, mark it as cleared, track your achievements.

Alas, winter in Chicago has long been associated with “claiming” parts of the public way. Adopt-a-Sidewalk attempts to capitalize on this impulse for the good of pedestrians, minus the lawn furniture and household detritus. (And we’re not the only ones trying to expand the definition of wintertime dibs to the sidewalk itself.)

Again, this has been one weird winter. Snow is scarce and temps are routinely above 40. If it ever does snow again, though, Adopt-a-Sidewalk is ready to promote community responsibility and actual sharing. We partnered with local startup OhSoWe to integrate neighborhood-based sharing into Adopt-a-Sidewalk. Locate your sidewalk — or a parcel you’d like to help out on — and instantly see who around you is willing to lend shovels, salt, even a snow blower.

It’s been noted that the City creating its own apps is a bit of a departure from our data-centric approach to date. (Noted, I might add, in the most strenuous way, with real constructive criticism from engaged residents.)

The truth is that having Mother Nature on the critical path to deployment is a tough, stressful thing. (She’s neither agile nor a fan of the Gannt.) We knew snow was coming and we knew we needed Plow Tracker up for the first major storm. Launching an app was something that could not slip. Adopt-a-Sidewalk, while built with volunteer assistance, was partially an effort at proving that municipal code sharing is real and viable. Both of these builds demonstrate that the City will create apps when there are reasons to do so. But that in no way detracts from our belief that the community and the marketplace are the sources of real innovation that come from Chicago’s open data.

And we have that too. Chicago Shovels’ last major app category showcases community-built applications. The two most useful are actually wintertime reworkings of earlier incarnations.

Last year civic über-developer Scott Robbin built SweepAround.us, an app for alerting residents the night before the City would be sweeping streets in their area so they could move their cars from the street (avoiding a ticket). This was the perfect app for tweaking to accommodate a system for alerts about the City’s 2″ Snow Parking Ban. SweepAround.us became 2inch.es.

Similarly, Robbin’s wildly popular wasmycartowed.com was updated to include automobile relocations due to snow emergencies.

A slew of winter-related resources round out the site, including a number of winter-related apps from last year’s Apps for Metro Chicago competition, information on how to become part of the City’s official volunteer “Snow Corps”, one-click 311 request submission, FAQ’s, and subscription to Notify Chicago alerts.

Chicago Shovels is the city’s best example to date of the value of open data. Transparency and accountability (Plow Tracker), reuse and sharing (Adopt-a-Sidewalk), business creation (Clear Streets), efficiency and ease-of-use (2inch.es and wasmycartowed.com) — these are the outcomes of a policy of exposing the vital signs of the city.

Now if it would only snow — and stick.

“Can you switch to Pandora?”

Beat Research Chicago continues. And wow is it fun. But can you determine where in this set I was asked to stop by the bouncer? (I did stop. Quintessential needle scratching off the record. Finished the recording at my desk when I got home.)

Speechifying

Lotta public speaking in the next few weeks. Most are local. If you’re interested in technology and urbanism come on out for a conversation.

University of Illinois Chicago College of Urban Planning Friday Forum

Friday, Feb. 24, 12p

“Data-Driven Chicago”

[detail]

University of Chicago Computation Institute Lecture

Monday, Feb. 27, 4:30p

“The City Is a Platform”

[detail]

City Club Public Policy Luncheon

Tuesday, March 6, 12p

[detail]

South by Southwest Interactive

Austin, TX

Monday, March 12, 12:30p

“The Future of Cities: Technology in Public Service”

[detail]

I’m particularly excited about that last one as I get to share a panel with Chris Vein, Nick Grossman, Abhi Nemani, Nigel Jacob, and Rachel Sterne. Perhaps the conversation will focus on just what the hell I am doing on the same stage as such accomplished folk. If you’ll be at SXSW, you should definitely drop by for this one.

Update from Beat Research Outpost #2

The Chicago incarnation of Beat Research has hit full stride. Jake, Jesse, and I are now in a twice-monthly groove (ahem) at Villains in the South Loop. And the first Wednesday of each month we overlap with the fantastic Urban Geek Drinks. All I need is for a NASA meetup to move in and I’ll pretty much have every interest covered.

Here’s my set from last night. Sanford & Son, music for Sith lords, 1980’s classics, my first foray into house (I know, right?) and of course some Chicago love. Do enjoy.

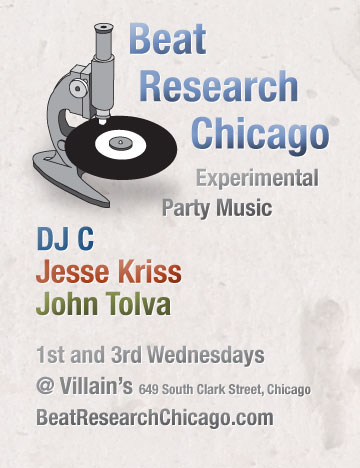

Beat Research Chicago begins

Here’s part of my set from the inaugural Beat Research Chicago at Villains last night. Fairly stompy with a bit of dubstep, drum and bass, and crazy Facebook users thrown in.

It’s the first time I’ve used Ableton with Serato in a live setting. Not a complete trainwreck. There’s hope.

Details and upcoming show info here.

Open data in Chicago: progress and direction

In a wonderfully comprehensive overview of Government 2.0 in 2011 up at the O’Reilly Radar blog Alex Howard highlights “going local” as one of the defining trends of the year.

All around the country, pockets of innovation and creativity could be found, as “doing more with less” became a familiar mantra in many councils and state houses.

That’s certainly been the case in the seven-and-a-half months since Mayor Emanuel took the helm in Chicago. Doing more with less has been directly tied to initiatives around data and the implications they have had for real change of government processes, business creation, and urban policy. I’d like to outline what’s been accomplished, where we’re headed and, importantly, why it matters.

The Emanuel transition report laid out a fairly broad charge for technology in his office.

Set high standards for open, participatory government to involve all Chicagoans.

In asking ourselves why open and participatory mattered, we developed the following four principals. The first two, fairly well-established tenets of open government; the last two, long-term policy rationales for positioning open data as a driver of change.

First, the raw materials. Chicago’s data portal, which was established under the previous administration, finally got a workout. It currently hosts 271 data sets with over 20 million rows of data, many updated nightly. Since May 16 the portal has been viewed over 733,201 times and over 37 million rows of data have been accessed.

But it’s the quality rather than the quantity that’s worth noting. Here’s a sampling of the most accessed data sets.

- TIF Projection Reports

- Building Permits (2006 to present)

- Food Inspections

- Vacant and Abandoned Buildings Reported

- Crimes – 2001 to Present (more block-level crime data than any other city, updated nightly)

Here’s a map view of the installed bike rack data set.

As a start towards full-fledged performance management, we launched cityofchicago.org/performance for tracking most anything that touches a resident: hold time for 311 service requests, time to pavement cave-in repair, graffiti removal and business license acquisition, zoning turnarounds, and similar. Currently there are 43 measurements, updated weekly. Here’s an example for average time for pothole repair.

To be sure, all this data can be inscrutable to residents. (One critic of the effort called it “democracy by spreadsheet”.) But the data is merely a foundation, not meant as a end in itself. As we make the publication of this data part of departments’ standard operating procedure the goal has shifted to creation of tools, internally and in the community, for understanding the data.

As a way of fostering development of useful applications, the City joined its data with Chicago-specific sets from the State of Ilinois, Cook County, and the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning to launch an app development competition. Anyone with an idea and coding chops who used at least one of the City’s sets was eligible for prize money put up by the MacArthur Foundation.

Run by the Metro Chicago Information Center, Apps for Metro Chicago was open for about six months and received over 70 apps covering everything from community engagement to sustainability. (You can find the winners for the various rounds here: Transportation, Community, Grand Challenge.)

Here are some of my favorite apps created from the City’s open data.

- Mi Parque – A bilingual participatory placemaking web and smartphone application that helps residents of Little Village ensure that their new park is maintained as a vibrant safe, open and healthy green space for the community.

- SweepAround.us – Enter your address, receive an email or text message letting you know when the street sweepers are coming to your block so you can move your car and avoid getting a ticket.

- Techno Finder – Consolidated directory of public technology resources in Chicago.

- iFindIt – App for social workers, case managers, providers and residents to provide quick information regarding access to food, shelter and medical care in their area.

The apps were fantastic, but the real output of A4MC was the community of urbanists and coders that came together to create them. In addition to participating in new form of civic engagement, these folks also form the basis of what could be several new “civic startups” (more on which below). At hackdays generously hosted by partners and social events organized around the competition, the community really crystalized — an invaluable asset for the city.

Open data hackday hosted by Google

Beyond fulfilling a promise from the transition report, why is any of this important? The overarching answer is not about technology at all, but about culture-change. Open data and its analysis are the basis of our permission to interject the following questions into policy debate: How can we quantify the subject-matter underlying a given decision? How can we parse the vital signs of our city to guide our policymaking?

The mayor created a new position (unique in any city as far as I know) called Chief Data Officer who, in addition to stewarding the data portal and defining our analytics strategy, is instrumental in promoting data-driven decision-making either by testing processes in the lab or by offering guidance for problem-solving strategies. (Brett Goldstein is our CDO. He is remarkable.)

As we look to 2012, four evolutions of open data guide our efforts.

The City-as-Platform

There are a variety of ways to work with the data in the City’s portal, but the most flexible use comes from accessing it via the official API (application programming interface). Developers can hook into the portal and receive a continuously-updated stream of data without manually refreshing their applications each time changes happen in the feed. This changes the City from a static provider of data to a kind of platform for a application development. It’s a reconceptualization of government not as provider of end user experience (i.e., the app or service itself), but as the provider of the foundation for others to build upon. Think of an operating system’s relationship to the applications that third-party developers create for it.

Consider the CTA’s Bus Tracker and Train Tracker. The CTA doesn’t have a monopoly on providing the experience of learning about transit arrivals. While it does have web apps, it exposes its data via API so that others can build upon it. (See Buster and QuickTrain as examples.) This model is the hybrid of outsourcing and civic engagement and it leads to better experiences for residents. And what institution needs a better user experience all around than government?

But what if all City services were “platform-ized” like this? We’re starting 2012 with the help of Code for America, a fellowship program for web developers in cities. They will be tackling Open 311, a standard for wrapping legacy municipal customer service systems in a framework that turns it too into a platform for straightforward (and third-party) development. The team arrives early in 2012 and will be working all year to create the foundation for an ecosystem of apps that will allow everything from one-snap photo reporting of potholes to customized ward-specific service request dashboards. We can’t wait.

The larger implications of platformizing the City of Chicago are enormous, but the two that we consider most important are the Digital Public Way (which I wrote about recently) and how a platform-centric model of government drives economic development. Bringing us to …

The Rise of Civic Startups

It isn’t just app competitions and civic altruism that prompts developers to create applications from government data. 2011 was the year when it became clear that there’s a new kind of startup ecosystem taking root on the edges of government. Open data is increasingly seen as a foundation for new businesses built using open source technologies, agile development methods, and competitive pricing. High-profile failures of enterprise technology initiatives and the acute budget and resource constraints inside government only make this more appealing.

An example locally is the team behind chicagolobbyists.org. When the City published its lobbyist data this year Paul Baker, Ryan Briones, Derek Eder, Chad Pry, and Nick Rougeux came together and built one of the most usable, well-designed, and outright useful applications on top of any government data. (Another example of this, from some of the same crew, is the stunning Look at Cook budget site.)

But they did not stop there. As the result of a recent ethics ordinance the City released an RFP to create an online lobbyist registration system. The chicagolobbyists.org crew submitted a proposal. Clearly the process was eye-opening. Consider the scenario: a small group of nimble developers with deep subject matter expertise (from their work with the open data) go toe-to-toe with incumbents and enterprise application companies. The promise of expanding the ecosystem of qualified vendors, even changing the skills mix of respondents, is a new driver of the release of City data. (Note I am not part of the review team for this RFP.)

One of the earliest examples of civic startups — maybe the earliest — is homegrown. Adrian Holovaty’s Everyblock grew out of ChicagoCrime.org, which itself was a site built entirely on scraped data about Chicago public safety.

For more on the opportunity for civic startups see Nick Grossman’s excellent presentation. (And let’s not forget the way open data — and truly creative hacker-journalists — are changing the face of news media.)

Predictive Analytics

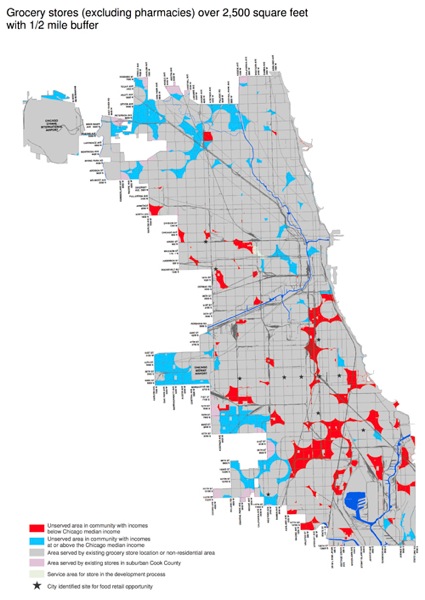

Of all the reasons for promoting a culture of data-driven decision-making, the promise of using deep analytics and machine learning to help us isolate patterns in enormous data sets is the most important. Open data as a philosophy is easily as much about releasing the floodgates internally in government as it is in availing data to the public. To this end we’re building out a geo-spatial platform to serve as the foundation of a neighborhood-level index of indicators. This large-scale initiative harnesses block- and community-level data for making informed predictions about potential neighborhood outcomes such as foreclosure, joblessness, crime, and blight. Wonkiness aside, the goal is to facilitate policy interventions in the areas of public safety, infrastructure utilization, service delivery, public health and transportation. This is our moonshot and 2012 is its year.

Above, a very granular map from early in the administration isolating food deserts in Chicago (click image for larger). It is being used to inform our efforts at encouraging new fresh food options in our communities. This, scaled way up, is the start of a comprehensive neighborhood predictive model.

Unified Information

The same platform that aggregates information geo-spatially for analytics by definition is a common warehouse for all City data tied to a location. It is, in short, a corollary to our emergency preparedness dashboards at the Office of Emergency Management and Communication (OEMC), a visual, cross-department portal into information for any geographic point or region. This has obvious implications for the day-to-day operations of the City (for instance, predicting and consolidating service requests on a given block from multiple departments).

But it also is meaningful for the public. Dan O’Neil recently wrote a great post on the former Noel State Bank Buiding at 1601. N. Milwaukee. It’s a deep dive into the history of a single place, using all kinds of City and non-City data. What’s most instructive about the post is the difficulty in aggregating all this information and the output of the effort itself: Dan has produced a comprehensive cross-section of a small part of the city. There’s no reason that the City cannot play an important role in unifying and standardizing its information geo-spatially so that a deep dive into a specific point or area is as easy as a Google search. The resource this would provide for urban planning, community organizing and journalism would be invaluable.

There’s more in store for 2012, of course. It’s been an exhilarating year. Thanks to everyone who volunteered time and energy to help us get this far. We’re only just getting started.

Reascent

Quick note about changes to the blog.

I’ve moved everything over from a Movable Type installation to the WordPress platform — something I have put off doing for years. I loved MT in the early years, but upgrades and patching became increasingly onerous, as the community of developers and support dwindled. So, yeah, WordPress.

The irony is that most of the pain of the transition was in ensuring that nothing much changed. The biggest hurdle was ensuring that the permalink structure of MT carried over for archived posts so indexed and internal URLs did not break. So, though the MT-to-WP import worked well, I had to touch every single post to make sure the permalink was correct. Add in various formatting issues and it was pretty hellish.

I got at least one inquiry this year about whether my new job at the city had forbidden me from blogging. That’s absolutely not the case. It was a combination of an increasingly-crufty blog platform, the way Twitter allows you to post an idea without actually fleshing it out, and just the timesuck of getting my feet at the city.

But that’s all fixed now. I fully intend to return Ascent Stage to the mix of way-too-long essays and who-cares ephemera that has characterized it in the past.

Not all the functionality (or design) of the old site is replicated here — and I am not entirely sure I got all the broken internal links. (External linkrot, well, that’s just the way of the Internet.) But it should be fairly stable.

Some reminders of other tendrils on the web:

Also, here’s my really big head on a “personal page”.

Do enjoy.

“Musical quality above genre coherence”

Pleased to announce that my pals Jake and Jesse and I will be hosting a local version of the venerable Beat Research.

On the first and third Wednesdays of the month we’ll deliver a few hours of experimental party music at Villain’s in the South Loop.

Jake (DJ C) started Beat Research in Boston in 2004 with Antony Flackett (DJ Flack) as a base for the genre-bending sets of music the two had been playing since the late ‘90s.

Since inception, Beat Research has hosted some of the best and brightest DJs and producers of underground bass music in the world, given a number of young luminaries their first gigs, and presented an utterly motley collection of tech-addled live performances. The long list of special guests includes DJ Rupture, Kingdom, Eclectic Method, Ghislain Poirier, Vex’d, edIT, and Scuba.

DJ C has since moved to Chicago (replaced by the incomparable Wayne Marshall) and, having missed those heady days in the Beat Research DJ booth, didn’t need much encouragement to be persuaded that this city could use its own explorations into innovative dance music.

Beat Research has been hard to match for anyone seeking out extraordinary sounds. Now Chicagoans can look forward to their own weekly session for discerning dancers and enthusiastic head-nodders.

More information and a mailing list sign-up at Beat Research Chicago. Toots at @beatresearch.

See you there, Chicago.