Rocks and hard places

In Ghana I took a trip with Margaret to her mother’s home village of Tanoboase (tah·no·bo·AH·say). It’s dirt poor, centered around the local voodoo shrine, and governed by a chief — in other words, a microcosm of what makes Ghana unique, world’s away from the urban centers of Kumasi and Accra.

Tanoboase is a good example of a town that would seem to be able to pull itself up a level. It is on the main artery from Kumasi to Tamale and it stewards a stunning historical-natural eco-tourism project. It’s close to the Boabeng-Fiema nature sanctuary (teeming with monkeys treated as children of the local gods) and it is near an amazing set of waterfalls.

And yet, Tano (as it is called) hasn’t been able to capitalize on the tourist dollars that overflow to similar areas near the slave sites of Cape Coast.

Boase means ‘under the rocks’ and the landscape up in this region is forest punctuated by crazily-shaped summits popping out from the trees. The form of the rock — caves, natural bridges, smoothed planes, boulders balancing on points — suggests some powerfully-erosive water flow through here eons ago.

This all makes for arresting views so it wasn’t a surprise to learn that there’s a Catholic (Benedictine, to be precise) monastery nestled into a nook. Kristo Boase is a quiet little operation of only about a dozen men (a convent is slated to open next year). Mostly it is prayer and agriculture in a secluded, inspirational setting. The monks don’t observe silence but the place is supernaturally silent. You’re as likely to hear a monkey screech as anything else.

One especially interesting point for me was a visit to the monastery’s cashew orchard. I’ve written previously about the fascinating biology of the blister nut, so imagine my delight at being able to see acres of them on the tree. They don’t just eat the cashews — no, this is a Catholic monastery: they distill the nuts into a potent liquor.

It’s cashew schnapps. And it is odious. But I bought a bottle, as well as cashew jam. I’m a supporter of the blister nut.

From Kristo Boase we headed a short distance into the town of Tano — and by town I mean about a half mile of variously-dilapidated structures hugging the Tamale road. This was Margaret’s true homecoming. She had not been back to visit in 25 years, but before we were all out of the car family came running up to greet.

Margaret’s aunt herded us around from villager to villager. I couldn’t keep track of who was related and who wasn’t — but then, maybe that wasn’t even a distinction anyone made. It was as if the Chicagoan Margaret had just been up the road at the next village for a while.

Lots of furious chatting in Twi, lots of stares, but no one at all visibly perplexed at my radiant alabaster skin. I was with Margaret.

Tano’s two claims to fame — and sources of tourism, such as it exists — are the local voodoo shrine and the sacred grove, closely connected to one another. The shrine is an odd thing. It houses a dark room and a tabernacle-type bowl said to contain Taakora, head of the Akan nature gods. It’s run by a fetish priest and you’re allowed in for a small fee. Margaret would have none of it and insisted on staying outside the “evil” place. I had to go in, of course. Honestly I couldn’t see much — it was deliberately creepy and shadowy.

It’s remarkable how seemingly unfazed Ghanaians are by their overt, omnipresent displays of Christianity and their reverence for hyperlocal animist gods. Something like 70% of Ghanaians are Christian, with the remainder Muslim. Yet nearly all villages have some sort of local spirit who receives supplication and is the threat behind frequent curses being placed on people.

Margaret’s brother was cursed by a villager years ago for a perceived slight. Her family — singularly Christian — took no heed. Her brother later had surgery on his throat for some ailment that the villagers all took as proof of the fulfillment of the curse. Rather circular logic, but there it is. The simple fact is that most Ghanaians pray to a Christian God while respecting what they call “small gods.”

As is customary when visitors come to town we met with the local chief, the Tanoboasehene. He remembered Margaret too and even gave her a hug, which was odd since protocol requires you to speak to the chief through his assistant. Hugs apparently do not contradict the prohibition against addressing the chief directly.

Also a matter of custom is presenting the chief with a bottle of liquor, usually schnapps. (Hey hey, the blister nut saves the day!) A small quantity is then poured on the ground in remembrance of villagers past. Yes, this is precisely where the African-American “tradition” of “pouring one out for my homies” originated. You won’t be surprised to learn that in Tano it was done a bit more reverentially than in America.

From the shrine you depart for the Tano Sacred Grove, the real home of Taakora as well as the site of the origin myth of the local Bono people. It is also the location of a last stand of local Akan during the tribal wars and slave raiding of 17th century.

The grove is certainly treated as sacred. Everything in it is protected (hence its eco-tourism designation) and there is a vaguely temple-like atmosphere walking in the semi-darkness of the vegetation and overhanging rocks. There’s myth and ritual at every turn. (Apparently virgins who enter the grove to fetch water will go blind.) It can be plain eerie.

Once you make it up the rocks and peer out across the tops of trees you realize that, religious or not, it is a rightful source of pride for the locals.

Margaret of course wanted to know what I made of all of it. She wanted to know how we could help jumpstart tourism, anything to help. I’m not an expert on tourism of course, much less rural African economic development, but it seems to me the problem is basically infrastructural. Getting to Tano is a chore, if not downright risky.

The “main artery” is barely paved and has lots of lethally-overloaded trucks traveling at incomprehensible speeds. Most tourists hug the coast, visiting Elmina, Cape Coast, and possible Kakum National Park. But there is a subset that ventures into the Ashanti inland empire and this would be Tano’s target group — if only they could get there.

The problem is the road. Open up the bandwidth and good things can happen. It’s the network economy of the industrial age: connectivity doesn’t just move stuff about, it multiplies the value of stuff. Without dependable physical access Tano can’t participate in the economic revitalization of the rest of the country.

But Tano isn’t going anywhere. Like most villages cut off from the grid of urban services, they’re largely self-sufficient. And the Sacred Grove is obviously enduring and legally protected to stay that way. The road will come.

A chosen few

Preparations for next year’s South by Southwest festival are underway and the panel picker is live. If you love me you’ll take a moment and vote for the two panel proposals that I’ve had a hand in.

The panel picker is a way of giving voice to the community at large about what the actual lineup of speakers should be. It isn’t wholly a popularity contest as the editorial board and staff have a hand in what finally gets selected, but feedback via the picker is a large part of it.

So here they are.

The Street is a Platform

Cities abound in data generated by their inhabitants (virtual worlds, city websites, online media) and created automatically by systems or monitoring. How does this online manifestation of the city interact in tangible ways with urban design and informal urban constructs? Is there such a thing as “the street as platform”?

This is a joint proposal with the inimitable Andrew Huff. And credit where it is due: this topic is almost wholly informed by this amazing post by Dan Hill.

Entrepreneurship in the Belly of the Beast

Small is beautiful at SXSW. From Getting Real to starting up, the ethos is largely anti-large corporation. This attitude overlooks one of the most satisfying professional accomplishments: doing your own thing while working for The Man. This presentation uses examples to offer strategies for making the corporation work for you.

Subtitle: Why Working for a Gigantic Company Isn’t As Bad As SXSW Would Have You Believe. This is my first (possibly last) submission for a solo “panel”. Just me on stage, a single target for the barbed arrows of the audience.

You do have to create an account to vote, but that’s not much to ask for a lifetime of my eternal gratitude, a firm handshake, possible hug, and sip of my drink next time we meet, is it?

A happening in China

Meanwhile back at the ranch …

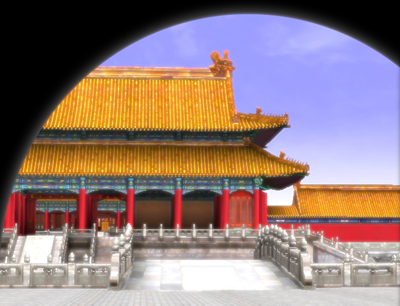

The launch date for The Forbidden City: Beyond Space and Time is now final. No, really it is. October 10, 2008. Beijing, China. See you there or in-world?

http://www.beyondspaceandtime.org

Don’t have any idea what I’m talking about? Well, it has been over two years.

UPDATE: The virtual world is live and can be found at www.beyondspaceandtime.org.

Call of the wild

In Kenya I stayed in a tent camp — not at all a luxury and a great way to extend the daytime safari thrill of being surrounded by animals. It was a thrill mostly unseen as the night came alive with noises that were always just outside the radius of the feeble gas lanterns around the camp.

Maasai tribesmen, hired by camp, patrolled the grounds at night, but it was still unnerving. Perhaps even more so when I’d start to wonder why we needed guards in the first place.

Cracking branches, rustling in the brush, and occasional screeches in the distance — it all made getting up to take a leak outside the tent at night positively terrifying. In fact the night before I arrived a lion came into camp at night and roared for about twenty minutes. The Maasai said it was just “talking” to its pride.

Coincidentally I had been reading a fascinating survey of 20th century music that mentioned in passing a study by two psychologists exploring the reason that certain musical passages give people the chills.

Their theory? It’s related to the call of the wild, which also explains the feeling of hearing an animal cry in the distance in a dark tent.

In our estimation, a high-pitched sustained crescendo, a sustained note of grief sung by a soprano or played on a violin (capable of piercing the ‘soul’ so to speak) seems to be an ideal stimulus for evoking chills. A solo instrument, like a trumpet or cello, emerging suddenly from a softer orchestral background is especially evocative.

Accordingly, we have entertained the possibility that chills arise substantially from feelings triggered by sad music that contains acoustic properties similar to the separation call of young animals, the primal cry of despair to signal caretakers to exhibit social care and attention. Perhaps musically evoked chills represent a natural resonance of our brain separation-distress systems which helps mediate the emotional impact of social loss.

Put another way, a solo instrument breaking free from the larger family of sound evokes in humans a kind of separation anxiety, an empathetic response that, like separation, is largely fear-based. And this response, the authors posit, is evolutionary. It’s related to animals (or human babies) calling out for attention. The call of the wild is a call of isolation. And isolation is scary.

They continue, attempting to explain the chills further.

In part, musically induced chills may derive their affective impact from primitive homeostatic thermal responses, aroused by the perception of separation, that provided motivational urgency for social-reunion responses. In other words, when we are lost, we feel cold, not simply physically but also perhaps neuro-symbolically as a consequence of the social loss.

“Homeostatic thermal responses” … yes, a hug. Chills as symbolic response to a lack of skin contact with others of your group. (Consider this image of a monkey baby clung to the bottom of its mother.)

See also a podcast from today’s Guardian on related evolutionary insights from music.

The Gold Coast

Our work in Ghana is finished, though the projects themselves are just begun.

I think we’ve made some difference with Aid to Artisans. They now have a very comprehensive analysis of their producers’ chain of supply from raw material to end consumer, video documentation of same, a set of recommendations on revamping their website including a redesign, and a roadmap for e-commerce. I’m pleased.

I’m also exhausted, and dirty, and homesick. But there’s one last adventure. I’m headed to Kenya tomorrow for a four-day safari on the Masai Mara, edge of the Serengeti. It’s a tent trek: no electricity, running water, or (can you believe it?) net access. Leaving all my gadgets in Accra. Offline, gridless, naked.

I have so much more to write about Ghana. Amazing fishing villages, a visit to a voodoo shrine, and playing in a tennis tournament as the only obruni. But it’ll all have to wait.

Thanks for reading this past month. Back in the fold after the safari!

(Full photo and video set is here, if you’re interested.)

Brass

Part six (of six) of the Ghanaian Handicraft series.

I’ve left the most complex handicraft until the end. I’m ashamed to admit how long it actually took me to figure out just what the heck was going on. A metallurgist, I’m not. But it is also arguably the coolest craft I learned. Here’s why.

Brass artisans take take the trash of technology — gears, circuit boards, wires, pipes — and transform it into art. It seems so right — such a fitting way to repurpose what otherwise would be non-biodegradable and in some instances toxic. (Glass bead artisans do something similar with discarded bottles.)

Specifically brass workers strip zinc and copper where it can be found and, though the level of impurity is high, they’re able to forage quite a bit.

But let’s back up. Making brass is relatively easy compared to getting it into the shape you want. Basically the art in this craft is all about the mold. It starts with long strings of honeybee wax. How the wax is shaped is exactly how the envisioned product will look. That is, where wax is in your model is where the liquid brass will harden. So get it right.

Charcoal is the material around which or through which you place the wax. It holds things in place. So, as in the video above let’s say you are making hollow, decorative spheres (for a necklace, for instance). A charcoal ball at the middle supports the wax decoration which will eventually becomes the brass.

OK, follow me on this. It hurts the brain a bit. Charcoal is packed around the finished wax model too. So basically you have the shape of the final product, in wax, completely surrounded by charcoal. Then this is all encased in a mud and straw crucible.

The key to it all is that there is no wax isolated completely inside the crucible. It all touches some other wax and is finally connected to strands of wax that poke out of the charcoal. See where this is going?

The crucibles are heated around a fire and the wax melts. It is drained out — thanks to nothing being isolated and the “channels” of wax that stick out of the mold. What you have is a perfect inverse mold of what you’re trying to make. Just pour in the brass (melted obviously) and let it set. Chip away the charcoal and voila! Brass from trash.

More brass-making video here.

Sally Struthers go home

Been struggling with how to put into words something I’ve felt visiting the poorer areas of Ghana.

Like most Westerners my concept of poverty in Africa is heavily informed by aid campaign advertisements. (I blame Sally Struthers completely.) Pre-programmed, one just sort of expects to find misery and unhappiness: sobbing, curled children with distended bellies; emaciated frowns from doorways; a total lack of joy.

I have seen none of this. In fact, if there’s any emotion I see more frequently than others it is happiness.

Now, before you say that I have confined myself to upscale, urban areas, I’ll note that most of the first two weeks’ work was in the field in tiny villages without electricity, running water, or any infrastructure whatsoever.

Certainly there is much misery and want in Africa. Failed states, pestilence, warfare — take your pick. But the longer I am in Africa the more I realize that we’ve been conditioned to believe that Africans are not happy. Purely from a aid organization sales perspective this makes sense: if people are happy with their plight in Africa why send your support check in?

It comes down to this: standard of living is not the same thing as quality of life. Would Ghanaians love to have other amenities that first-world citizens enjoy? Perhaps. Are they in abject misery because they do not? No way.

In thinking that Ghanaians’ quality of life suffers because their standard of living is below ours we’re making a cliched blunder, guessing at the perspective of someone else through the filter of your own cultural sensibilities. It’s arrogant. And demonstrably incorrect.

Africa could use help, there’s no doubt. But aid will never be effective if we provide it based on caricatures of behavior meant to tug at us emotionally. So, Sally, go home. I know children lack food and die of horrible illnesses in Africa. But images like that mask the real complexity of the needs and promise of African society. Let’s be more honest.

Clay

Part five of the Ghanaian Handicraft series.

As in many cultures, pottery is made from clay in Ghana. Yet as a craft it is hard to find here, largely because it is considered utilitarian, with a market that’s almost completely domestic. People use the pots, bowls, and vessels in everyday life.

Unlike other handicraft that is created at some distance from the source of the raw materials, potting happens close to the river banks that provide the clay, presumably because it’s a pain to move large quantities of the dense, wet material.

We visited the tiny village of Nfensi and were taken to their river. It was one of those glad-I-took-my-malaria-meds moments. (Luckily we were there during the daytime, before the virus-toting Anopheles skeeters come out.)

Once hauled up from the water the clay is pounded repeatedly to loosen it up. (The pounder uses the same tool that smashes open yam and cassava for fufu, incidentally.) There’s a further step of kneeding, then the potter slices off as much clay as he’ll need and slaps it on the wheel.

The potter’s wheel is completely manual. One guy cranks it while the master shapes the clay.

It happens so quickly and effortlessly — probably not surprising given that they turn out approximately 1,000 items every three days.

Once dried, the clay objects are prepared for the igloo-shaped kiln. It’s infernally hot around the oven which the artisans actually walk into to stack the clay pots. Then the “door” to the oven is bricked up and the fire is allowed to go for a few days. The door gets broken back down and out come the finished, though unadorned pieces.

There is an export market that consumes larger, more finely decorated pieces, but it is overshadowed by the more “traditional” wooden export market. To many Westerners, Africa means wood carvings (masks, statues, etc). But those consumers who are interested in owning the most “real” African goods — what one study calls “authenticity buyers” — might look to pottery as an alternative.

More clay pottery video here.

Ghana One: Who’s Who?

With the final week upon us I thought I’d introduce you to my teammates from the inaugural IBM Corporate Service Corps mission in Ghana. (Update: I added myself.)

Ritu Bedi

Alias: Sweet Mango

Home: Delhi, India

Primary Skill: Breakfast negotiation.

Little-known fact: Acid reflux almost caused Ritu to bail out of the Kakum Canopy Walk.

More on Ritu’s assignment.

Arindam Bhattacharyya

Alias: Hookah

Home: Kolkata, India

Primary Skill: Has a sixth sense for locating good Indian food anywhere on the planet.

Little-known fact: Arindam can eat more than you. Try him.

More on Arindam’s assignment.

Roslyn Docktor

Alias: Happy Camper

Home: Washington, DC, USA

Primary Skill: Clipper-based hairdressing.

Little-known fact: She’s been to Zambia. No really, just ask her!

More on Roslyn’s assignment.

Pietro Leo

Alias: Tee Wee

Home: Bari, Italy

Primary Skill: Injecting humor when it is least expected or appropriate.

Little-known fact: Looks equally crazy when clean-shaven.

More on Pietro’s assignment.

Julie Lockwood

Alias: Gertie

Home: Boulder, CO, USA

Primary Skill: Can frighten small Ghanaian children to tears simply by looking at them.

Little-known fact: Has visited 90% of the toilets and “near-toilet experiences” in Ghana.

More on Julie’s assignment.

Fred Logan

Alias: Chief

Home: Ottawa, Canada

Primary Skill: Capital infusion to the local souvenir and handicraft industries.

Little-known fact: Taught disco dancing in the 1970’s — even appeared on TV.

More on Fred’s assignment.

Stefan Radtke

Alias: Shortwave

Home: Bonn, Germany

Primary Skill: Can speak in morse code.

Little-known fact: Set up a full shortwave radio station at our hotel.

More on Stefan’s assignment.

John Tolva

Alias: Mule

Home: Chicago, IL, USA

Primary Skill: Perspires more than his body weight every four hours.

Little-known fact: With enough tin foil, Stefan’s shortwave antenna, and an intricate yoga pose John can steal wireless from the hotel down the street.

More on John’s assignment.

Charlie Ung

Alias: Flip-Flop

Home: Vancouver, Canada

Primary Skill: Imperturbable.

Little-known fact: To mosquitos Charlie is mostly a bony frame transporting a big bag of delicious blood.

More on Charlie’s assignment.

Peter Ward

Alias: Biscuit

Home: Warwick, England

Primary Skill: Extraordinarily detailed blogging.

Little-known fact: Peter has wireless access in his room and, as such, is the object of a team conspiracy to abduct and relocate him.

More on Peter’s assignment.

IBM@10

Today I mark one decade in the full-time employ of IBM. No, I don’t believe it either.

Back in 1998, as the go-go days of the first boom were about to go-go away, I was struggling between two job offers. IBM’s was low, a producer role at the relatively iconoclast Interactive Media group in Atlanta. The other, with a start-up consultancy called iXL, was much sexier, promising a higher salary and 10,000 options (oh, the promises).

To this day I don’t really know why I chose IBM. Might have been the I in the acronym — the suggestion of a career spent globetrotting and doing business in different cultures. Which is precisely what it turned out to be, though I’ve taken the jetsetting to some kind of perverse extreme. Being in Africa while marking this “anniversary” rather puts an exclamation point on it.

My first office space, IBM Interactive Media, Atlanta

10 years is a completely arbitrary duration of time, but it does feel important somehow. More important than the extra week of vacation, that is. (Seriously, does anyone count vacation days anymore?)

I’d known since the beginning of the year that I wanted to use the anniversary as an evaluation point. And then the Corporate Service Corps opportunity came up I thought, what a perfect way to evaluate my career than to be yanked out of it for a month and plopped into a wholly unfamiliar environment.

With two weeks to go in Africa, I have no stunning insights to share as yet. I suppose if any do come it will be when I am back in the US and can reflect a bit. I do know what I miss and what I don’t (a future post, of course), but as for what I want to be when I grow up … still thinking firefighter, librarian, or World Dictator. Will let you know how it all turns out. (By the way, for those interested in what it is I actually do you can learn more here.)

So how did I celebrate this occasion? I waited until shortly after midnight last night, silently marked the anniversary, went over to the pool, and jumped in fully dressed. Seemed appropriate somehow.