Maine holiday

Just back from a first-ever trip to the coast of Maine. What an amazing place.

Couple of tips for the uninitiated. You’ll encounter lots of puns on the name “Maine”: Maine-ly Antiques, Maine Drag, The Maine Attraction. Avoid these at all costs. Also, an easy clue as to how greedily a place wants your tourist dollars is to note the amount of signage and text that spell things according to the Maine accent. If you see more than one reference to “lobstah, chowdah, and beeya” leave. Immediately. Lastly, if you hate the Red Sox do not visit Maine.

To boil down what Maine thinks it has to offer I present you with the following list:

- lobster

- blueberries

- moose

- the way life should be

- a carbonated beverage called Moxie

- lighthouses

- puns on the state name

But it is really so much more than that. Have a look.

Testing 1-2-3

Coudal Partners has released it’s third edition of Field-Tested Books. It’s a stunner.

FTB is a collection of short reviews that explores the connection between the subject of a book and the actual location it was read. Like Rob Gordon’s autobiographical organization of his record collection in High Fidelity, the idea is that reading is not a act sliced off from the context in which it happens. The real world has a way of bleeding into the written world, and vice versa. FTB is a compendium of crossovers.

This year Coudal is releasing the reviews as a bound book. Looks gorgeous, as does the poster and the process behind it. Kudos to Steve and the entire Coudal crew for editing such a cool volume. And for inviting me to contribute.

For geo-types, I’ve put together a quick map showing the geographical dispersal of the reader reviews. Some are guesses — for point-to-point air and road travel I used the midway as the location — and others don’t exist at all. Happy trekking!

Throwback

I’m headed to Wrigley this afternoon to catch the Cubs in their current hot streak. It’s going to be a unique game. Apparently today the club will celebrate 60 years of being televised by WGN by trying to emulate a game from 1948.

Norman Rockwell, The Dugout

There have been retro days before, but this one is fairly unique. In addition to the 1948 uniforms (which for the opposing Braves is a Boston uniform) the telecast will be in black-and-white for the first few innings. Camera angles will be limited and the center field camera (which provides the batter close-ups) will be offline. Certain vendors will be offering 1940’s-era victuals at 1940’s-era prices. How cool is that? More info here.

Fans are encouraged to dress the part too, but I’ll be damned if I am going to put on a suit and fedora. Well, maybe just the fedora. How does one dress for 1948?

Retrograde

I was shuffling files around recently and came across an archive of my first personal website. It wasn’t Ascent Stage, but a site called hypertext :: renaissance (you see, the lowercase and double-colon were edgy) that I built when I was in graduate school in 1996.

Click for annotations and prepare to mock.

The search engine stares back

To commemorate the birth of artist Diego Velázquez Google today pulled a funny with their homepage logo.

I wrote about the strange interactive aspects of this painting a month ago. It’s particularly apt for a search engine that’s always looking back at its own viewers. Compare.

I didn’t realize Sergey and Larry read Ascent Stage. Welcome, sirs.

Artisan

So, you may know that I am headed to Africa for five weeks on a special assignment for IBM. It is called the Corporate Service Corps and it is a unique undertaking for a large corporation. For any company, for that matter. It is the Peace Corps meets multinational company meets corporate citizenship. I leave on July 10.

You’re thinking, good luck trying to sell a blade server or consulting in Ghana. Or, you shameless pigs, Africa needs basic infrastructure, not computing firepower. You’re right. But it isn’t either of those. We’re not selling; we’re completely cut off from the network of peers in the company that makes us corporate workers. We’re guns-for-hire working for tiny businesses.

This program is the most globally-minded program I’ve seen IBM undertake in ten years. The idea is simple: send IBM’ers to places on the cusp of entering the global market and where we have no real presence. Might never have, in fact. But doing right by the global community isn’t just about doing so in markets in which we do business. You’re not believing that as you read it, but it is true. We are completely OK with the fact that we may never do business in Ghana, but that’s not really the point. The point is that it is frankly stupid to pigeonhole knowledge anywhere in the world. Helping one place will flow elsewhere. Better businesses in one place ultimately is good for other places. It’s not unlike environmental responsibility, actually.

There are multiple assignments per location. Mine is with the NGO Aid to Artisans. It’s goal: “to enhance income levels and employment generation in the craft industry in Ghana through product design and development, business training, market development, advocacy and advisory services.”

My goal? To help them develop an e-commerce site and understand their supply/value chain.

We’ll see. But I couldn’t be more excited.

Metadata and spring cleaning

It’s taken years, but I finally have backup where I want it. (Oh yes, dear readers! It’s another post about data backup. Recline your chair and prepare for a mind-blowing post.)

My reasons for backing up seem to be changing. Certainly there’s still the raw, precious data. Family photos and video, certain media projects — these things have to be saved for posterity. But increasingly my reasons for wanting a backup are more about state than data. I want to return to the state my machine was in more dearly than I want the data it once contained.

Think of it in more concrete terms. What if you everything in your house — every single physical item — had a double in a storage facility? What if every time you bought anything you bought two and put one in a self-storage bin? Then your house burns down (and all your loved ones are safely vacationing on Maui). You can reconstruct your life from the storage facility, but it will be a massive pain in the ass. The state is all fooked. The effort involved in getting it back to a livable order is overwhelming, basically the same thing as moving — an act which ranks just slightly below death of a spouse in terms of personal stress.

Ideally you’d want a legion of robotic moving specialists to reconstruct your house according to the old plans and place everything back as it once was. A bonus would be the option to redirect the robots as the spirit moved you, but at the very least you’d have an automatic replica. This is the source of my fascination with bootable clones.

The fact is, most of my data is replicable. My iPod and laptop all contain enough of my music library to reconstruct it if the main machine should fail. My calendar is online. Personal mail’s all IMAPped up to the Great Google in the Sky. Work e-mail, replicated from servers. Photos are all on Flickr; video at any number of services. The set of truly precious, non-online-dwelling data is getting smaller and smaller by the day. Basically source files only.

My prediction is that in the near future state is all we will care about. You won’t even think about data being local or remote. But you will care about speed-to-recovery. And that’s all about the little things, how your machine behaves, how your kitchen was organized before the fire.

There are corollary effects of this attitude. Recently to alleviate some of the space pressure of five people in a home we decided to clean up some of the impromptu areas of storage in the house that had persisted since we moved in. You know what I’m talking about. Boxes that never got completely unpacked. Stacks of crap that made do in a guest bedroom only because you didn’t know where else to put it.

I undertook the foolish exercise of building an attic in my garage. I can hardly hammer a nail straight much less build a structurally sound platform. Most of what we moved up there was non-essential: books, college notebooks (wanted to throw away but couldn’t — I’m going to need that Intro to Lit Crit some day,damnit!), winemaking equipment, random crap.

So I got it all up there. Stored. Except it wasn’t really stored — wasn’t really backed-up — unless I knew it was there. And this again is the influence of Google. Unless you can search for it, unless you know precisely how to get it back, you might as well throw it out, delete it. So I took photos of everything up there, where it lay in the attic. And for the books, well, it got a bit geekier as I finally finished cataloging and noting the location of every last volume with the superb Delicious Library.

Do I care about most of that crap up there? No. Do I care that I know the state of that crap. Absolutely. And that’s the thing. If the garage burned down I would be OK. The stuff is replaceable. The index to that data is not.

Maybe I’m overthinking this because my father and brother are in the self-storage business. But I think not. Spring cleaning for me is really spring tagging.

The biophony of Trout Lake

I spent the long Memorial Day weekend with high school pals, fathers, and siblings on a fishing trip in northwestern Ontario. (You may recall the write-up from a few years back featuring Bruce the ax-wielding moose-hunter.)

We’ve been making the trip for decades, but it was only this time that I realized the full impact of truly being off the grid: no roads, no landlines, no cell service, obviously no computers, no Internet. It was a fantastic shock to the system.

The disconnection is not abrupt. You fly into Winnipeg and all is well. Cell still works; iPhone happily sucking in data. You drive east out of Manitoba into Ontario, all good, happy banter in the car, people still covertly checking devices for refresh. Once past Vermillion Bay things start to get dodgy, connection in and out, sucking a shrinking air pocket inside a sinking vehicle. Then Red Lake. Nothing but landlines. Connectivity here is only for the old school essentials such as calling home to loved ones. You wonder, maybe this is the only connection that matters.

The next day you take the float plane to Trout Lake. The last moment of connectivity departs in a cataclysm of noise as the 1940’s era prop aircraft motors up to speed. You put on old school noise-cancelling headsets (i.e., huge rubber and foam cans) and the world goes silent. When you’re finally on the dock in Trout Lake you may as well still have the headset on because everything is utterly still, cloyingly quiet.

You better like the people you with because you can’t tweet your discontent. Of course, liking the people you’re with — and the staff at the camp — is the reason for the trip. But the importance of human communication rather hits you in the face.

And not just verbal communication. Most of the guides on the lake are native Canadians, Indians in the old parlance of the US. Famously taciturn, these guides know the lake like you knew your childhood neighborhood — but they’re not conversationalists. Most respond in grunts or curt phrases. Some open up occasionally (if, sadly, the chance of alcohol is involved) but even then it is awkward and quick to dissolve. As such, the communication throughput becomes even narrower. But the signal-to-noise ratio is off the charts.* From wideband always-on to hand gestures and body language in 24 hours.

So you’re left to listen. And that’s when it hits you. This place is loud. Lapping waves, birdcalls that can only be described as symphonic, overlapping frog croaks, the last floes of ice in the crunching throes of dissolution, indeterminate animal noises that frighten, even the low white noise of the biomass on the shore recycling itself.**

It’s an internet. Which is to say, it is a massively-scaled, multiply-threaded system of signals with intention. The birds aren’t chirping because its pretty; they’re communicating. The ice isn’t making noise with purpose but it serves a purpose. Moose and other shallows-dwelling animals hear it and adjust behavior.

But there is human-made noise, of course, all gas-powered. Float planes every few days, outboard motors every few minutes, and the camp generator way back in the woods always. It’s an ecological disruption, if only aural. Not nearly the damage we’re causing to the environment in other ways, but damage just the same.

Bernie Krause calls nature’s soundscape biophony and contrasts it with human-made noise, anthrophony. He’s a field-recording scientist who catalogs the ways in which man’s din interferes with the communication networks built in to nature, inanimate and living. It’s no different than spectrum interference between your router and cordless phone. Two signals with the same acoustic imprint are going to degrade each other.

The real reason the soundscape on the lake is an internet is because it works around outages; it isn’t point-to-point. When a motorboat storms through a bay certain communications are disrupted, to be sure. But the toad croak network continues with shorter hops (so to speak) between rebroadcast. Eagles depart for quieter aeries from which to communicate. And of course most signals are simply queued for later transmission. It’s remarkably effective … to a point. When the noise is constant (as in the generator) the soundscape alters the landscape firmly, pushing the communication past a certain radius where it all works again.

It’s only in a place as serene as Trout Lake that you realize all this, of course. Laws requiring sound abatement mostly exist only in dense urban areas whose ambient noise level is already ridiculously high. Exurbia and rural areas — the places with the most at stake — hardly give human-made noise a second thought.

(It’s interesting to contrast this experience with the other annual fishing trip I take with my family on the Gulf in Texas. There, in a boat even miles out fishing the intercoastal waters, you’re always in range of a cell tower. Guides follow the fish by talking to each other on phones constantly. You wonder what the fishing would be like if the guides had to jack into nature’s network rather than Verizon’s.)

Back on Trout Lake, you return to camp after a day fishing for a congenial bullshitting happy hour, just talking at a table face-to-face. Dinner preparation is announced with one bell ringing, serving by two. The night unwinds by a fire where you watch the aurora screensaver in the sky and, mostly, just listen to nature’s nocturnal packet switching hit overdrive.

More photos and video here.

* High signal-to-noise is the very reason for no roads in. If you open up that bandwidth the pressure on the lake ecology increases exponentially, reducing the high value signals: huge, abundant fish.

** Some of the dads are hard of hearing and use in-ear aids. The near-absence of human noise and direct soundlines on the lake surface allow them to hear sounds far better (such as from boat to boat hundreds of yards apart) than they can even do in a small room around a table.

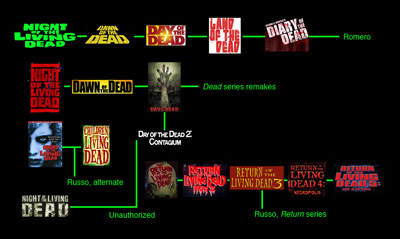

Lessons from Zombiefest, Part the First

Gather ’round, members of the living. You are about to become educated on the finer points of the undead film genre.

A while back my brother and I watched every film begotten (and misbegotten) from Romero’s classic Night of the Living Dead — 16, plus one trailer.

That’s right. We’ve done the hard work so you don’t have to.

Zombie films almost always contrast human incompetence, ignorance, or incompatibility with the external threat of the revenant hordes. Which is to say, humans nearly always screw themselves worse than the zombies do. Zombies are not stalkers or serial killers. They frighten because they are single-minded and unstoppable — unstoppable because of quantity rather than invulnerability. Like a virus. In fact, substitute viruses for the undead and you basically have the same movie.

Even so, fear of the undead usually stands for something else. It’s always the fear of others, a group that shifts with mainstream society’s notion of norms. So, for instance, it has been argued that Night of the Living Dead‘s zombies represent drug-addled hippies, out of their minds and focused on getting their fix. It was 1968, after all. That symbolism is debatable — and it gets a lot more complex, though no less true, when the zombies become somewhat sympathetic in later films — but it is clear that Romero at least always tries to depict the pitched battle of humans vs. undead as something more than just that.

A note for the true fan, there are spoilers below because, well, all zombies spoil eventually. Also, some of the clips are gory, duh.

We watched the films based on release date, but they are here grouped according to main series and remakes.

Lastly, please forgive the stylistic schizophrenia of the write-ups. That’s what you get when you mix a collaborative spreadsheet and several personal kegs of beer over a weekend of sedentary film-viewing.

Romero Series:

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

The granddaddy, near perfect. Black-and-white. Zombies are not slow, mindless or lumbering. They are the living recently-dead, not rotting corpses. Some even use tools to kill. (Joey: “That may be the most un-zombielike thing I have ever seen.”) No crawling out of the grave. Some confusion about whether they can be killed in any way that a human can be or if you have to shoot them in the head (which becomes the standard later on). Seems they cannot “infect” the living. Mention of a Venus satellite coming back to Earth and starting the “epidemic”. Mr. Cooper is a dead ringer for Rob Corddry. Odd fixation on taxidermy. Little girl zombie confronting her parents as disturbing now as it surely must have been in 1968. Lead character is a black man, unusual for 1968. He never gets it from the zombies but is killed in the end (mistakenly?) by a group of rescuers that looks exactly like a lynch mob. Best quote: “They’re coming to get you, Bahr-bah-rah.”

One of the reasons that Night spawned so many remakes and derivatives is that it has lapsed into the public domain. As such the entire thing is online for your viewing pleasure.

Rating: ★★★★★

Hard to argue with a movie whose setting is the locus of the real undead in America: the suburban shopping mall. This continuation is conceptually brilliant, but executed not as well as the original. Possibly influenced by Network (released two years earlier), the film starts in a TV edit suite broadcasting news of the sprawling zombie epidemic. (Interesting flipside to the always-on TV in the first film, basically a character unto itself. At one point in Night someone justifies his actions by saying “Well, the television told us to.”) Action shifts to a mall where a small band of survivors takes refuge from the madding crowd, a consumerist utopia vs. unstructured lust (the urban street, natch). The agent of zombification is now officially viral. The voice of reason, again, is a black man. Firsts: Tom Savini (make-up effects auteur) cameos as a biker; disembowelment; helicopter scalping; obese zombie (rare!). Also, entire biker gang is drinking High Life, which in itself merits applause.

Here’s Savini fending off the shoppers, er, zombies and coming to his own end.

Rating: ★★★☆☆

An undead movie with a message. That sucks. Or rather, doesn’t live up to the Romero standard, which disappoints all the more. (For true suckage, we must wait for a few remakes, coming in future post installaments.) So, the outbreak is basically worldwide, lots of shots of overrun cities. A group of scientists and military folk hole up in a vast underground bunker. The scientists are running experiments on captured, shackled zombies because, you see, even zombies have feelings. Bud, the only zombie in any Romero flick that speaks a line, is the central figure. Behind him is this weird three cross motif on the wall. What is he, the messiah? The whole thing is paced through rubber cement, e.g. the first kill (of a zombie, no less) is 58 minutes into the film. The brainy scientists vs. brawny military disagreements tire after, oh, the first one. In the end, it’s too much preach, not enough gore. One of the sensitive humans says “How can we set an example for them if we act like barbarians ourselves?” Gag.

Here’s an unchained Bub actually shooting (and saluting) the head military guy, who is then gang-dismembered.

Rating: ★☆☆☆☆

Twenty years separate this from Day and thank god for that. This is a great movie. The world is completely overrun with the undead. Uninfected humans are barricaded in walled urban centers (hello Baghdad Green Zone!); there’s something of a comfortable equilibrium. Frequent sorties for supplies are undertaken outside the city in a heavily-armored truck-tank that can mow down zombies and distract them with fireworks (“sky flowers”). The twist is that the undead are beginning to remember things, are getting smarter, acting braver. Oh, also they learn to swim. There’s a bit of a zombies-are-people-too vibe which annoys and I’m no great fan of zombies seeking revenge (meaning they are compelled by more than just a hunger for flesh, boo), but overall this is one great flick. Dennis Hopper and John Leguizamo are fantastic.

Here’s the original, unreleased trailer that integrates some footage from the first three movies, plus the creepy quote from Night.

Rating: ★★★★☆

Stay tuned for the next riveting installment of the undead marathon recap. And for god’s sake aim for the head.

.jpg)