An update on the Marhaver Lab campaign

I turned 50 last month. It’s a funny age. Old for sure, but not ancient; closer to the end than the beginning, statistically. Maybe because of that memento mori I seemed naturally to be thinking less about the present and more about the future — a future far enough out that does not include me. And that got dark real quick given the state of our planet. In an effort to keep it light I wanted to do something that focused on the long term, something (however tiny) that contributed to the foundations of a healthy planet.

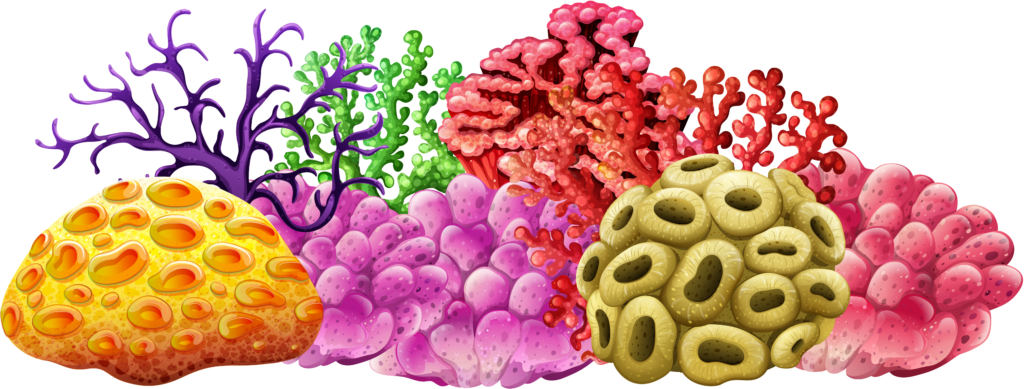

Enter Dr. Kristen Marhaver. I first met Kristen years ago after an Ignite talk she gave at the ORD Camp unconference. The whole talk was jawdroppingly insightful (and funny), but I remember one moment especially. She was describing the process of coral sexual reproduction, a not well-understood event that happens at night, whereby coral simultaneously release sperm and eggs into the water. These particles are positively buoyant so they all come to the surface. Kristen continued that the evolutionary brilliance of this is that the buoyancy effect turns a geometrically complex insemination problem in three dimensions (everything just willy-nilly colliding in the open water column) into a much more manageable two dimensional problem at the water’s surface. But here’s the real beauty: fertilized eggs then become negatively buoyant ensuring that they fall back to the substrate to try to grow and thrive. You go, evolution!

So, yeah, I’ve been interested in the science of coral reefs for a while. Following Kristen’s work, scuba diving reefs all over the world, and running my own little experiments at home — not exactly a side gig, but certainly a passionate avocation. Running a small fundraising campaign for Marhaver Lab to celebrate my 50th birthday seemed a natural thing to do.

I had no target in mind when we launched the project. Indeed, if anything I thought worst case a low raise would quantify just how few friends I had left after a pandemic. But, in a little over a week we raised just shy of $11,000 — far more than I could have hoped for. Family and friends donated (thank you!), but what really became interesting is how the campaign evolved in a few days to receiving support from people neither I nor Kristen even knew. The word got out, apparently, and people love baby corals.

I think no one loves baby corals more than Kristen, though. If you’re interested in the work she does, there’s a just-published piece on a “moonshot” project she was part of to cross-breed Elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) from Curaçao with the same species (exhibiting different environmental characteristics) from Florida. This is important as we look for ways to introduce heat-tolerance and other forms of climate resiliency into reefs worldwide. It’s called “assisted gene flow”. Basically Kristen’s a midwife of the coolest sort. And yet, as this excerpt notes, there’s still work to be done:

Marhaver thought that they had a five to 10 percent chance of success. To have hundreds of healthy coral now sitting in tanks barely crossed her mind. Conservationists are more attuned to the vibrations of endangerment, extinction, and loss. To have a moonshot succeed is unfamiliar territory. With the impossible now possible, the next hurdle is moving from the lab to the ocean, a leap that not everyone is comfortable with.

$11k isn’t a lot of money given how much it costs to perform the kind of lab-based and in situ work that Marhaver Lab undertakes. But it’s a start and more than that it’s a signal that a lot of people care about the complex interdependence of our planet’s health with even the smallest living creatures. I may not be ancient (yet) but coral organisms are and their well-being is inextricable from the well-being of our global marine environments. If the oceans fail, we fail. Venus is too hot. Mars is too dry. We have to make this third rock work.

Going Native

In the past year I’ve found myself becoming more and more interested in restoration ecology. I’m not an ecologist or a naturalist or even very environmentally-savvy, but I am working on it and it seems to me that the practice of restoring an ecosystem is a useful way of thinking far beyond its own application.

Malcolm McCullough, professor of architecture at the University of Michigan and one of the leading proponents of place-based interaction design, ends his fantastic 2004 Digital Ground with this historical blurb:

The expression going native apparently originated in nineteenth-century India …. [I]t began as a description of Englishmen wearing loose-fitting pajamas in public. This sensible adaptation to the sultry climate was seen as a token of deeper assimilations, particularly intermarriage, which the expression came to represent. Such practices were common enough amid mercantile colonization in the eighteenth century, but as foreign traders became rulers, the accompanying social tensions made assimilation taboo. Thus to the imperial British of the nineteenth century, “going native” was a crime. It represented a lapse of discipline and a descent into chaos.

This taboo pervades American culture today. To “go native” is to go niche, to be deliberately different. However logical it may seem, going native rubs up against one’s own cultural sensibility — and usually loses.

But here’s the thing: going native is nothing more than letting context drive design. When an industrial designer goes to the factory floor and interviews workers about how the process works, that’s context driving design. When a mobile phone maker spends time in a rural southeast Asian village watching how people communicate, that’s context driving design. And it all yields the very best, most sustainable products.

Waterproof envelope made from a leaf, Tano Sacred Grove, Ghana

It doesn’t often happen this way, of course. Design itself in the west is a semi-sanctified endeavor. The artist receiving divine, solitary inspiration: this is a myth that won’t die. (It may work for fine art, though you can argue that there’s no such thing as an artist immune to external influence.) Nothing happens in a vacuum.

William Morris said “you can’t have art without resistance in the materials” and he wasn’t talking about hitting a knot while whittling. Resistance here is merely constraint on free-form design and almost always a good thing. You may not produce a photo-realistic drawing with most of your crayon box broken, but you’ll certainly have to work harder. And hard work usually pays off.

So how does this relate to restoration ecology? Well, the living world itself is the world’s longest-running design charrette and if it and its engine of creation known as evolution have taught us anything it is that constraint over time produces the most lasting products. (Also, at least one pretty engaging game.)

The natural environment has for most of evolutionary history been the constraint under which life’s creative experiment has been run. Climate, geography, predators, food availability — all are pressures that snap the crayons in the box, factors that have culled the palette of what would have otherwise produced an infinite and totally unsustainable variety of life.

Luckily, the world is a harsh place. Just to survive is amazing, but to produce something beautiful or unique is astounding. Evolution is the perfect marriage of an indefatigable artistic drive and an unrelenting set of constraints. You could say that neither “wins” (an equilibrium, if punctuated) — or that they both win, always.

But that’s only in the scenario where naturally-produced constraint is the sole factor. And that, of course, has not been the case since evolution’s Mona Lisa — homo sapiens — slyly smiled its way onto the scene.

You might argue that human constraint is a natural constraint too. And I’ll buy that to a point. But the scale and scope of the impact of human beings on evolution — both negative (like pollution) and positive (like conservation) — vaults it into a new classification in my opinion.

For one, human behavior introduces all kinds of new variables into evolution’s experiment (e.g., the Aral Sea desertification). But more importantly, our impact on the natural world has divorced our adaptive behavior from natural constraint. Technology (or tool-making, something that makes us human in the first place) has greatly mitigated the effect the natural environment has on human behavior. People rarely need to go native.

Yes, when it is raining out you’ll grab an umbrella. Yes, when there’s a hurricane headed your way you’ll (usually) get the hell out. And it is true that human intelligence makes it impossible to conceive of a planet where we don’t modify our behavior in response of the environment.

Yet, it is the little things that add up. I think we can all agree that detonating nuclear bombs is a negative influence of human behavior on the natural order. But what about suburban lawns? How many people know how much water and gasoline they take to maintain and how many species native to the environment they simply cannot sustain? And this is merely the example most pertinent to restoration-based landscaping.

The point is merely this: natural constraint never goes away. The environment, the sum of natural phenomena, will always trump human artifice. Nothing built lasts forever. And since neither are we humans going away (fingers crossed), it is in our best interest to figure out how to balance this constraint with our own needs. We need to learn how to go native intelligently.

I’ve written previously about how I think Africa is a model here. Most Africans don’t have the ability to live beyond the constraints that the environment puts on their behavior. To be sure, this is the source of much woe and privation in Africa. But conceptually — consumption in line with an environment’s ability to sustain production — it is a behavior well worth imitating. It is, in short, a recipe for innovation.

And that’s why I am fond of my father’s project to return his lawn to native Illinois prairie. Yeah, it looks cool. And we get a visceral thrill of burning it down periodically. But the beauty is that it is a constant reminder of balance between human need (oooh, pretty!) and ecological compatibility. Evolution took a long damn time to figure out which flora and fauna could be successful in the Driftless Area of northwestern Illinois. Why on earth would we think we know better?

Our new prairie is a microcosm of behavioral equilibrium. On one side of the scale is the fact that it isn’t a real prairie, only a human-engineered approximation of one that suffers the challenge of artificially depleted biodiversity (one lawn ain’t gonna make all the native species return, especially if they are extinct) and also the challenge of being a native moat encircling a very artificial human-built house with all its environmental contributions. On the other side is the good news: no watering, no mowing, and most importantly a landscape that once again sustains the native animal life that evolved needing it.

This idea of balance, of “sensible adaptation,” of smartly going native, needs to be scaled up. It needs to inform all our decisions as de facto stewards of the planet. There will always be trade-offs, precisely because humans have extraordinary needs and an extraordinary capacity to make things better. Restoration ecology alone will not save the planet, but the ideas that undergird it just might.

This entry is cross-posted in a slightly-modified form on Prairie Works.

Fire and life

Africa affects me in little ways.

Like recently when I was contemplating my annual purchase of firewood. Burning real wood in a fireplace is one of my great loves during long Chicago winters. I easily tear through a cord per winter, sometimes needing extra. And yet, that’s a lot of wood for what is largely aesthetic comfort (though our basement needs all the heat help it can get).

So this year I wanted to learn more about my options. Usually I get wood from one of any number of local, similar operations. A couple of laborers-for-hire pull up in a pickup, throw a bunch of wood in a pile in your garage, and then depart. God only knows where they get this wood from. Or if the company has any interest in the sustainability of the forests from which the wood comes.

So I turned to Ascent Stage’s resident guest restoration ecologist, Cory Ritterbusch, for his usual clarity of insight. I asked about places in northern Illinois where I might deal with a firewood vendor who thinks about his source as much as his sale. Cory noted:

Right now our firewood industry has not been hit by the same environmental stewardship programs that paper and building materials have. So there is nowhere to point to for sustainable, managed firewood processes locally.

Most green thinkers choose their firewood by species to reduce the risk. Oak and Hickory are the preferred woods to burn in the fireplace, but that is done at the detriment of cutting very important slow-growing specimens.

Environmentalists will ask for Red Elm or “Elm” as they are usually standing dead trees having died due to Dutch Elm Disease. It is also a great burning wood offering high temperature, little ash and easy split-ability.

Didn’t know that. Did you?

The smell of burning firewood was constant in Ghana. In the morning, stepping out of my room to the call of the roosters; in the daytime walking down a crowded Kumasi street; at night when the smoke of a thousand dinners ascended and mixed above the town. The tang of wood on fire is for me essential Ghana. I came to love it.

But the wreckage it has caused! The denuded countryside, once rainforest, strikes you like returning to a loved home without any furniture in it. The same space, but not the same place. The soil, suddenly chemically-bereft of sustaining anything but what just got ripped out, is no longer landscape but ecological cul-de-sac. Redwood-sized trunks lashed to wheels and an engine barrel down dirt roads one after the other. it is stark cause-and-effect, easier to see than in the West with our complex chains of supply.

This is what Africa has done to me. Not a blinding moment of enlightenment, but many small moments that creep up without real thought. The things I saw there will be with me forever, ineradicable viruses of the imagination.

Africa is a way of thinking

I came to some startlingly common sense realizations while in Africa. For instance, its now clear to me that sustainable environment practices and Africa are inextricably linked. They aren’t separate matters or concerns or causes. To act on one is to act on the other.

Here’s the obvious part. Africa — and the entire “Global South,” as it is often called — stands to lose the most from planet-wide environmental deterioration. The fate of Africa has always firstly been tied to the environment. Even when you subtract out all the man-made horrors that Africa has seen life on the continent is shaped in deep ways by the ecological, geological, and meteorological hand it has been dealt. Subsistence agriculture, wars over limited (or precious) resources, lack of access to coasts, the range of the tsetse fly — all these things define life more immediately than the environment does (for now) in other places.

But there was insight too. A lesson, you could say, that the first world can learn from the third. Sustainability is a way of life for Africans. They don’t think about it as such. It isn’t a campaign or a movement like it has become in the West, but it is evident everywhere, woven into everything Africans do.

Simply put, Africans live with resource scarcity. They have not experienced consumption out of whack with production because it has never been a possibility.

For every place you see selling cars you see five places recycling every possible component of the cars. Usually its for repair, sometimes it is to create something utterly different.

Or take tro-tros, the ubiquitous, horn-happy minivans that criss-cross every part of Ghana moving people more efficiently than a bus system every could. It’s a totally decentralized, mostly private group taxi service. Mass transit on an unbelievable scale with no set routes at all. Need a ride? Flag a tro-tro. You’ll get where you’re going. (Not unlike hailing a “taxi” in Russia, though there rides are less frequent, less capacious.) While tro-tros are almost universally decrepit, smoke-belching buckets of bolts, the system as a whole is by far more environmentally friendly than private cars or even a fleet of taxis.

One fact of life in Ghana is the unreliability of centralized services. The electricity grid, for example, cuts out a few times every week. Just … off. Usually mid-day when it is hottest out. Yet this is not nearly as disruptive as it would be in the West. Partially this is just an attitude of resignation; that’s just the way it is. But because it’s the norm most places simply do it themselves with generators on standby (or have ways of manually doing what would otherwise be electrically-powered).

There’s no central water supply either so in urban areas private gravity tanks (or nearby streams) provide running water. The explosive growth of mobile phones is in part fueled by a lack of reliance on a centralized grid of services. It’s obviously not industrial age mega-infrastructure but more like modular, emergent services — build as you go, bottom-up. Like the Internet itself, basic services are built to work around outages.

To a Westerner this seems like privation but, looked at another way, it is a built-in constraint on excess usage. Self-sufficiency isn’t radical; it’s practical. And self-sufficiency naturally requires an intimate knowledge of one’s own patterns of consumption. You use what you have and nothing more. It ain’t rocket science.

So why is this a lesson? Certainly I’m not claiming that open sewers or power outages are the way forward. Nor should it be taken to mean that Africans are somehow immune to over-exploitation of resources.

Yet, Africa provides an example of what a society might look like that has so totally internalized sustainable living that it informs everything it does. Africa as a behavioral template, not a developmental one.

There are many paths that lead to this way of living within one’s means. You can choose to do it or you can be forced to because all your other options have been exhausted. Most of Africa has no other choice.

It took me a while to realize how pragmatic the idiosyncrasies of daily life are in Ghana. After first I thought the army of vendors on the road was a nuisance. They’re not “roadside” but in the middle of the road, often long lines of people selling the exact same thing — tissues, water, power strips, mangos, anything. (Even the mayor wants them off the road.)

But actually it makes a ton of sense because traffic is often such a mess. It’s like one huge drive-through mall. In the lingo of a typical consultant: they’ve monetized gridlock. It’s efficient and practical, such as at the toll stop pictured above. I’m not arguing for in-road vending so much as noting that what seems crude is often entirely sensible, bordering on ingenious.

It’s hard for non-Ghanaians not to do a double-take when they see women carrying staggering loads on their heads, but once the shock wears off you realize, wow, that really is efficient. The arms are free to do other things while the entire frame of the body distributes the load atop the spinal column. Also, it makes for good posture.

But the most practical form of carriage is the way babies are swaddled. Just a single sheet wrapped around the child who’s straddling the mother’s back and literally sitting atop her butt. I never once saw a child squirming or screaming and the moms looked similarly non-plussed. Again, the arms are free to do whatever.

What do baby swaddling and sustainable living have to do with one another? They’re both examples of deep-rooted pragmatism. It seems simple, even backwards sometimes, but the way of life I saw both in Ghana and Kenya was firstly about solving everyday problems. It’s largely coincidental that many of these problems are matters of production and consumption — the very basis on our misaligned relationship with the planet.

Let’s take some inspiration from Africa. It’s a plentiful, renewable resource, after all.

How to save America

With John 7,000 miles away in a third world country, I have decided to fill in for him. Now, taking his wife out for a night on the town could be a little awkward and very inconvenient for me. Instead, I have decided to guest blog on this widely revered Ascent Stage.

My name is Cory Ritterbusch, and I am the only ecologist that John knows. Some of you AS die-hards may remember my blog PrairieWorks being cited in the past. I practice a small but growing form of land conservation known as Restoration Ecology in the rural Midwest. Ecological Restoration, as a verb, is the practice of repairing a damaged or destroyed ecosystem. Let’s try to get our arms around the man-child that is ecological restoration to show you: How you can utilize it in some of your decision making, how to view the landscape in a new way, the power that humans possess and the damage we can reverse.

For millions of years American Indians and the ecosystem co-existed together here in America rather nicely. What is now corn and soybean fields were extensive prairies, savannas and woodlands harboring thousands of different species. Intermingled amongst these prairies were forests, wetlands, bogs, fens, and so on. There was a very smooth and seamless transition into one another without fragmentation. These ecosystems were on fire frequently, started by lighting strikes and by intentional means by Indians. It was a part of the natural process here in America for millions of years. With fire, the Midwest remained open without many trees. The plants living here adapted to these fires and became dependent on them for survival.

Beginning in the early 1800s pioneers began entering these wild areas and by 1850 the landscape had become extremely altered. Prairies were plowed into crop fields, woodlands were cut for timber and wetlands were drained. This had a detrimental effect on the species that had existed here for millions of years. With the suppression of fire and the introduction of plants from other continents, the conservative native plants had a hard time competing and were eventually extirpated. Luckily, small areas known as remnants were spared and botanists could study these areas to learn about them. These are now a benchmark for comparison and a seed bank for plant propagation. Today, restoration ecologists are mimicking the natural processes in hopes of recreating the glory of the prairie’s former past.

The landscape, agricultural and energy industries have also taken notice and are learning from these ghost plants of the past. We are now utilizing native plants to amend troublesome site conditions and are designing landscapes that provide a greater sense of place. The deep root systems that native plants formed after millions of years of harsh weather conditions are being utilized for many applications including: Controlling erosion, removing toxins from soils, creating landscapes that do not require water and fertilizers, planting flower filled areas in sub-par soil conditions and for producing ethanol. Native plants also offer a greater sense of place rather than utilizing the same set of plants from state to state and region to region, regardless of climate and soil types. For example, an Applebee’s restaurant chain will use the same building design and landscape design for all of its locations in today’s current streamlined thought process.

Much like Frank Lloyd Wright’s house designs incorporated elements of local materials, we are now doing this outdoors. Ironically, for the first time we are beginning to create landscapes that are of American influence rather than English and Japanese, the norm for the last two centuries. Replacing lawns, which have large maintenance requirements, with short grasses native to the western Midwest is just one example of how we can utilize native flora to reduce financial and natural resource strains for the betterment of humanity. Soon, we hope that the 55 billion dollar landscape industry can be trained in local plants rather than the sharpening of blades at the cost of a depleting water supply.

History comes full circle sometimes. The plants that we destroyed to create food to feed a nation can now be utilized to solve many important issues here at home. Utilizing perennial prairie plants for ethanol, installing plants that reduce labor inputs, attracting wildlife, reminding us where we are, cleaning our air and water, all while stabilizing soil in the process can be useful tools as we look towards the future. The plants that were once used to sustain an entire population of native people may do so again.

Thanks to John for allowing me to preach the power of native plants.

Cory Ritterbusch

The biophony of Trout Lake

I spent the long Memorial Day weekend with high school pals, fathers, and siblings on a fishing trip in northwestern Ontario. (You may recall the write-up from a few years back featuring Bruce the ax-wielding moose-hunter.)

We’ve been making the trip for decades, but it was only this time that I realized the full impact of truly being off the grid: no roads, no landlines, no cell service, obviously no computers, no Internet. It was a fantastic shock to the system.

The disconnection is not abrupt. You fly into Winnipeg and all is well. Cell still works; iPhone happily sucking in data. You drive east out of Manitoba into Ontario, all good, happy banter in the car, people still covertly checking devices for refresh. Once past Vermillion Bay things start to get dodgy, connection in and out, sucking a shrinking air pocket inside a sinking vehicle. Then Red Lake. Nothing but landlines. Connectivity here is only for the old school essentials such as calling home to loved ones. You wonder, maybe this is the only connection that matters.

The next day you take the float plane to Trout Lake. The last moment of connectivity departs in a cataclysm of noise as the 1940’s era prop aircraft motors up to speed. You put on old school noise-cancelling headsets (i.e., huge rubber and foam cans) and the world goes silent. When you’re finally on the dock in Trout Lake you may as well still have the headset on because everything is utterly still, cloyingly quiet.

You better like the people you with because you can’t tweet your discontent. Of course, liking the people you’re with — and the staff at the camp — is the reason for the trip. But the importance of human communication rather hits you in the face.

And not just verbal communication. Most of the guides on the lake are native Canadians, Indians in the old parlance of the US. Famously taciturn, these guides know the lake like you knew your childhood neighborhood — but they’re not conversationalists. Most respond in grunts or curt phrases. Some open up occasionally (if, sadly, the chance of alcohol is involved) but even then it is awkward and quick to dissolve. As such, the communication throughput becomes even narrower. But the signal-to-noise ratio is off the charts.* From wideband always-on to hand gestures and body language in 24 hours.

So you’re left to listen. And that’s when it hits you. This place is loud. Lapping waves, birdcalls that can only be described as symphonic, overlapping frog croaks, the last floes of ice in the crunching throes of dissolution, indeterminate animal noises that frighten, even the low white noise of the biomass on the shore recycling itself.**

It’s an internet. Which is to say, it is a massively-scaled, multiply-threaded system of signals with intention. The birds aren’t chirping because its pretty; they’re communicating. The ice isn’t making noise with purpose but it serves a purpose. Moose and other shallows-dwelling animals hear it and adjust behavior.

But there is human-made noise, of course, all gas-powered. Float planes every few days, outboard motors every few minutes, and the camp generator way back in the woods always. It’s an ecological disruption, if only aural. Not nearly the damage we’re causing to the environment in other ways, but damage just the same.

Bernie Krause calls nature’s soundscape biophony and contrasts it with human-made noise, anthrophony. He’s a field-recording scientist who catalogs the ways in which man’s din interferes with the communication networks built in to nature, inanimate and living. It’s no different than spectrum interference between your router and cordless phone. Two signals with the same acoustic imprint are going to degrade each other.

The real reason the soundscape on the lake is an internet is because it works around outages; it isn’t point-to-point. When a motorboat storms through a bay certain communications are disrupted, to be sure. But the toad croak network continues with shorter hops (so to speak) between rebroadcast. Eagles depart for quieter aeries from which to communicate. And of course most signals are simply queued for later transmission. It’s remarkably effective … to a point. When the noise is constant (as in the generator) the soundscape alters the landscape firmly, pushing the communication past a certain radius where it all works again.

It’s only in a place as serene as Trout Lake that you realize all this, of course. Laws requiring sound abatement mostly exist only in dense urban areas whose ambient noise level is already ridiculously high. Exurbia and rural areas — the places with the most at stake — hardly give human-made noise a second thought.

(It’s interesting to contrast this experience with the other annual fishing trip I take with my family on the Gulf in Texas. There, in a boat even miles out fishing the intercoastal waters, you’re always in range of a cell tower. Guides follow the fish by talking to each other on phones constantly. You wonder what the fishing would be like if the guides had to jack into nature’s network rather than Verizon’s.)

Back on Trout Lake, you return to camp after a day fishing for a congenial bullshitting happy hour, just talking at a table face-to-face. Dinner preparation is announced with one bell ringing, serving by two. The night unwinds by a fire where you watch the aurora screensaver in the sky and, mostly, just listen to nature’s nocturnal packet switching hit overdrive.

More photos and video here.

* High signal-to-noise is the very reason for no roads in. If you open up that bandwidth the pressure on the lake ecology increases exponentially, reducing the high value signals: huge, abundant fish.

** Some of the dads are hard of hearing and use in-ear aids. The near-absence of human noise and direct soundlines on the lake surface allow them to hear sounds far better (such as from boat to boat hundreds of yards apart) than they can even do in a small room around a table.

The slovenly wilderness

My father, brother, sister and I have a dorky little bookclub. We don’t meet nearly as often as we used to, but it’s still an excuse to get together for lunch once in a while and make fun of each other for misreading a given book. We rotate selection responsibility, a responsibility which includes the book and a place for lunch somewhat related to the topic of the book.

The current selection was mine, The World Without Us by Alan Weisman, a thoughtful if scattershot exploration of what would happen to the human-built world if we all suddenly disappeared. It is billed as a “thought experiment.” One of these experiments concerns envisioning what would happen if there were no one to maintain the petropolis of oil machinery, tanks, and pipes that dominate the sprawl between Galveston Bay and Houston. (Some of it would break down and rust into the soil and some of it would blow up, igniting the network of delivery pipes that connect to the rest of the country.)

The best parts of the book aren’t hypotheses about catastrophe or collapse but examples of built places since abandoned, mini-worlds without us: the DMZ in North Korea, much of Turkish Cyprus, the Mayan empire. Short version: natures takes things back far faster than you’d think but there are certain things that our actions have wrought — billions of microscopic plastic shards in the oceans, for example — that are going to be part of the world until the sun blows up and ends it all.

It’s an ecological manifesto, of course, an extreme version of pointing out that being green isn’t just mitigating our disequilibrium with the environment going forward; it’s about undoing what’s been done in the past too. That’s the point of positing the highly unlikely (though not impossible) scenario in which all the polluting human beings suddenly disappear: the planet’s still fucked.

Chew on that, this Earth Day.

We met to discuss the book at the Garfield Park Conservatory, a really wonderful 100-year-old greenhouse complex that’s part of the city’s park district. A microcosm of the world without us, no?

Well, not exactly. For one, even a botanical park like this is completely artificial; these plants would never live together naturally. But more interestingly, in a world suddenly without us a conservatory would actually be a real threat to the environment. The glass and structure would fail rather quickly, exposing the flora and its seeds and pollen to the winds and animals. Much of it would die off but some of it, nearly all “invasive” to local ecologies, would make its way out into the environment and wreak havoc. That ain’t natural. (For those of you who’ve seen I Am Legend you’ll note that this is a similar scenario to the predators from the Bronx Zoo competing with Will Smith for game in Times Square.)

We ate outside — the weather topped 70F today. Only as we left I noticed that the benches we were sitting on had carved on them one of my favorite poems, Anecdote of the Jar by Wallace Stevens. Seems appropriate for today.

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The jar was round upon the ground

And tall and of a port in air.It took dominion every where.

The jar was gray and bare.

It did not give of bird or bush,

Like nothing else in Tennessee.

You won’t believe it, but it was nothing but coincidence that we chose today to meet about this particular book. I of course enjoyed it. I like my book club meetings laden with meaning.

What being green means to most of America

My parents have let the lot at the home in Galena, IL return to natural Illinois prairie. This is cool in a natural-historical way, and certainly beautiful*, but it also takes a bit of work to rehabilitate the land after the tumult of excavation and construction. So, they hired the company Prairie Works as landscape consultants who’ve guided the process of planting and, in the case of the photo below, burning of the grasses as happens naturally every so often.

Recently I came across the Prairie Works blog maintained by Cory Ritterbusch and have been surprised at how interesting it is. City boy adds blog about prairie grass to his reader, imagine that. Consider the post about the culture of lawns in America:

In 2006 the American lawn reached a higher status among its citizens – it became the country’s largest irrigated crop. Between our golf courses, sports fields, town squares and residential lawns turfgrass now covers an amazing 40 million acres, or 80 percent, of non-farmed land.

40 million acres, sweet jesu. That’s a lot of agriculture for show.

Although the 1/2-acre area of grass that is carefully manicured by its owner seams rather harmless, it is the large-scale ramifications of millions of such owners that prove to be devastating. In 2005 it took 238 gallons of water per person to irrigate 40 million acres of turfgrass, which are being mowed with 800 million gallons of small engine gasoline and kept green by 70 million pounds of chemicals. All this costs an estimated 30 billion dollars annually (2005). The effects on water and air quality are staggering as are the 68,000 injuries sustained annually while mowing.

Am I the only one staggered by the amount of gasoline and water that it takes to keep something up that is in most cases an extension of a home’s aesthetic rather than functional?

Oddly enough, lawn care advertising confirms that most residential lawn care is a losing battle against climate, pests, traffic and other variables, unless more efforts, including watering and chemicals, are applied to the cause. The 70 million pounds of chemicals applied to turfgrass annually represent a higher concentration of chemical input than any other form of agriculture worldwide.

My suburban friends have probably stopped reading by now and written this post off as the rantings of a guy with a postage stamp-size parcel of grass in the city. Against lawns? That’s un-American! But I have to believe that there’s a sizable majority of middle America who, in suddenly eco-conscious America, believes that their ginormous lawns are part of the solution to environmental problems. I’m not sure that’s entirely true, but happy to read otherwise in the comments.

* Even if it does have an abandoned lead mine on the property. Ecologically sound or not?

Nature, 4. Tolva family, 0.

Microscopic to macroscopic, we’ve taken it the hard way across the full spectrum of natural world nastiness in the last two weeks. Powers of 10 gone bad.

Let us start with the tiniest of living evils, the virus. A few weeks ago we headed out on our first truly long-haul road-trip adventure and final hurrah of the summer. All five of us crammed into one car. Luggage everywhere. Fishing rods strapped to the roof. Hello, Clark Griswold. We left Chicago at 9PM on a through-the-night journey to far northeastern Oklahoma, a friend’s lakehouse. Strangely I had never considered OK to be drivable, but in fact the border is only as far from St. Louis as St. Louis is from Chicago. Doable, if miserable.

3AM. All three kids asleep. Bliss. Then, our one-year-old daughter awakens with a cough straight out of a horror flick and inhalation distress that was truly terrifying. She was sick, clearly. Wife says, that’s croup. Just a nasty little virus that we usually combat at home with a steamy shower, a jaunt out into the cold night air and/or medication. We had none of these. So, wife then says, we need to pull over right now. I agreed that we needed to, but, see, we were on the freeway squarely bisecting East St. Louis, the city that began the tradition of Illinois towns on the east side of the Mississippi being hellish mirror images of their counterparts on the other side. I protested, citing the well-being of all of us in the face of the well-being of one of us. But thelovelywife threatened my well-being if I did not pull off to assist our youngest and, you know, I’m selfish about my own personal safety, so I did. Here’s a short video I shot at this moment.

We survived this escapade but decided we had to stop over the bridge at the St. Louis Children’s Hospital. I went to grad school at Wash U. so I knew this was a quality institution, but I was unprepared for just how amazing it was when you need it, even in the wee hours of the morning. Still, seeing your toddler in a hospital gown is a troubling thing. Sleepless and with two other kids in their pajamas in the ER it was all we could do at this sight to keep our composure. She got some steroid shots and we were on our way. But we couldn’t go all the way to Okie. Just didn’t seem right with Typhoid Mary in the car. So we decided to re-route to Galena, Illinois a small town in far northwestern Illinois where my parents have a place. We rolled in at 8:45 PM the next day. Just 15 minutes shy of 24 hours (minus ER) in the car. More on this at the conclusion of this saga.

Scale up, if you will, from the dastardly virus to the sustaining yeast fungus. As a culture, we owe much to this little bugger, but I’m currently greatly dissatisfied with it. I decided to embark on a raspberry wine fermentation last weekend. (You may recall the bloody mess that was picking these delicacies on my parents’ property, the aforementioned Galena residence.) So I squashed and squashed. You can’t run these things through a grape press, alas, and have to squeeze them whole in a cheesecloth bag. It was open-heart surgery.

We ended up with five gallons of juice. It smelled heavenly. I added the sugar, took the temp, measured the specific gravity, had the concoction positively yearning for ferment then added the yeast and … nothing. OK, not a problem, might take a night. But no. No foam, no gurgle, no incipient smell of alcohol. This was a problem because I did this after the kids were asleep hoping to avoid their bacteria-laced touch and endless questioning. It was not to be. The next morning I checked the fermentor — still no hot yeast-on-sugar action — and my kids were all over the thing. I had to explain it all, which resulted in this classic quip from the six-year-old: “Mommy, mommy, did you know that yeasts are little critters that poop alcohol!?” I’ve done nearly everything I know to get the fermentation going, but as of today, no luck.

Scale up again to the charming urban indigene known as Rattus norvegicus. We’ve had a bit of rat problem of late. Early summer storms knocked our garage door off its track. We fixed it, but the fix left a gap at the bottom where the little nasties let themselves in nightly. We saw them scurrying out when we’d lift the door but only understood the extent of the problem when we peered into the corner where we store some of the 19 strollers we own. Rat shit everywhere. In every nook, every cranny. Son said “Hey Daddy, look at all the rotten raisins in the baby seat.” Um, not exactly.

As soon as they banished the thoughts of the cute vermin from Ratatouille and Flushed Away the kids were immediately obsessed with helping me rid ourselves of the bastards. But of course, as with the wine, they had to be right in the action playing away in the rodent feces. I finally shooed them away and fired up the leaf-blower to shoot out the very last of the Bubonic particulate matter. Stupid. I was immediately in the eye of a small hurricane of enclosed, whirling crap. (Woke up the next morning with a sore throat and some truly Dickensian snot.)

No rat spotted as of today, though we’ve identified their lair in the foundation of the couch house next to us. Next weekend promises chicken wire and concrete poured into their holes. Take that, suckers! Good fun.

Scale up now from the natural to the Natural. As in Mama Natura. (Bitch.) And rewind to the aborted trip to Oklahoma. We’re on our way to Galena moving up the western edge of Illinois through such metropolises as Peoria, Galesburg, and Savanna — a trip worthy of a Sufjan Stevens album. Just two hours from the blessed relief of a home we know the skies turn apocalyptic. Wife and I were barely coherent from lack of sleep. This was hour 22 of 24 awake. It all went straight to hell as an amazing supercell unloaded on us. We were on the Great River Road that snakes up the Mississippi through tiny towns so at least one cardinal direction, west, was cut off for our escape route should we have seen a twister. Luckily we didn’t but it was a biblical torrent. In a way maybe it was a good thing. The adrenalin powered us through the last hours of our odyssey from St. Louis in our roving petri dish of a car.

Moving eastward these storms were on a bee-line for Chicago. They slammed the city as we all convalesced from our road trip in Galena. We didn’t realize the extent of it until we arrived home that Sunday. There was evidence of the maelstrom everywhere: trees down, transformers blown, standing water. We arrived in time for our annual block party. A small affair, literally one block of the thousands in Chicago. The funny thing is that because of the storm one side of the street had power, the other had none. Being rather neighborly around these parts about a dozen homes from my side had strung extension cords across the street to power certain vital gizmos on the other side. This ad hoc wiring was made more surreal because there were no cars on the block due to the party. I’ll remember this show of support when we’re all irritable and threatening each other with a shovel-based death for parking spots come winter.

Scrolling further out I’m sure you can find a meteor headed straight for my home, but this has not happened yet so please post it as a comment when I am but a mixture of carbonized ash and interstellar dust. Thanks.

Brita city

Bioswales, blackwater, and benthic nets. Microbial fuel cells, hydroponic disinfection, and pervious pavement.

Were you thinking about these things when you were in college? I certainly wasn’t. Perhaps I should have been, because the student teams in the History Channel’s City of the Future Engineering Challenge sure seem like they have bright futures ahead.

Picking up on the popularity of their “Engineering an Empire” series, the History Channel last year held a design competition in LA, Chicago, and NYC. Professional design teams had one week to design a vision of their city 100 years in the future in such a way that would be sustainable much beyond.

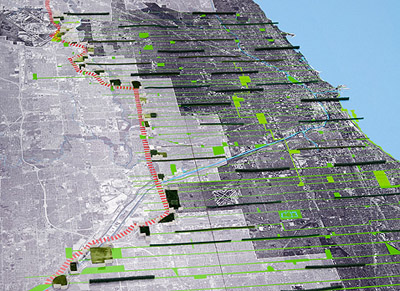

The winner in Chicago was Urban Lab, a small outfit on the south side whose Growing Water submission presented a Chicago infrastructure that recycles 100% of the water it needs by un-reversing the flow of the Chicago River back into Lake Michigan, resurrecting the (currently) century-old idea of an Urbs in Horto “Emerald Necklace” of parks ringing the city proper, and carving latitudinal waterways alongside “eco-boulevards” to make the whole city-sized water filter work.

That was sorta the easy part. The heavy lifting was left for the students in the second phase who actually had to present the engineering behind it all. As a sponsor of the event (with a keen interest in promoting engineering, math, and science) IBM was asked to provide a judge for the second phase. This was me. I was elated. I wasn’t at all qualified, but I have been writing about the subcontinental divide, reversed river, and future Chicago here for a long time. The blog as street cred.

Undergraduate engineering student teams were fielded by the Milwaukee School of Engineering, Purdue University, U of I Urbana-Champaign, two from U of I Chicago, and Northwestern University. The presentations were simply remarkable. These kids — and they were kids to be sure — had put an amazing amount of time and thought into the tricky real-world problems of re-architecting a city at its most basic level. None of this was done for course credit.

Prior to the presentations the judges received ample supporting documentation for each solution: dozens of pages of equations backing up claims, diagrams, 3D renderings, and a bounty of specialized words to make the verbophile delight for hours. Advective. Biomimicry. Turbidity. Effluent. I loved it all.

The essence of the challenge in engineering Urban Lab’s design was how to design the filtration of the water in the terminal parks and along the eco-boulevards east of the subcontinental divide. Most of the teams focused on how this filtration would happen. Others also stressed the challenge of separating graywater (wastewater with everything but poop), blackwater (poop), and potable water while being able to accommodate the “100-year-storm” (Chicago, though above sea level, is essentially a swamp). Still others focused on the Urban Lab sidenote that existing santitation tunnels (not needed in their design) could be used for expanded mass transit. One team went into great detail about a Chicago Maglev train. This might be a great next project for the CTA as their current Brown Line expansion will likely finish up around 2106.

The team from UIUC won the competition with their notion of EcoTowers — residences at the terminus of eco-boulevards that pass graywater through a “biomimetic forward osmosis membrane bioreactor.” Duh. Of course they do. The towers themselves provide further filtration by running a curtain of nearly-clean water down the windows of the highrises for UV disinfection. Like living under a waterfall or inside the Beijing Olympic natatorium. Brilliant.

Chicago has a very long way to go to approach anything like this design, of course. Green roofs are a start, I suppose. Just glad people are working the problem. Even more glad that career-minded students are taking it so seriously. Bravo to all the teams.

See also on Ascent Stage: City of the Future and 10 Visions, an exhibition from the Art Institute