Supercharged culture-geeking

This past Monday, IBM and the Office of Digital Humanities of the NEH convened a bunch of smart folks to talk about what humanities scholars would do with access to a supercomputer, real or distributed. I had been looking forward to this discussion for months, if not years in the abstract. It was a wonderful convergence of two of my life interests.

We had a broad representation of disciplines — a librarian, a historian, a few English profs, an Afro-American studies professor, some freakishly accomplished computer scientists, and a bunch of “general unclassifiable” folks who perfectly straddle the worlds of technology and culture.

The Library of Trinity College, Dublin

The grid has about a million devices on it and packs some serious processing power, but to date the only projects that have run on it have been in the life sciences. We were trying to think beyond that yesterday.

My job was to pose some questions to help form problems — mostly because, outside the sciences, researchers just don’t think in terms of issues that need high performance computing. But that doesn’t mean they don’t exist. It’s funny how our tools limit how we even conceptualize problems.

On the other hand you might argue that this is a hammer in search of a nail. OK, fine. But have you seen this hammer?

Here’s some of what I asked:

- Are there long-standing problems or disputes in the humanities that are unresolved because of an inability to adequately analyze (rather than interpret)?

- Where are the massive data sets in the humanities? Are they digital?

- Can we think of arts and culture more broadly than typical: across millennia, language, or discipline?

- Is large-scale simulation valuable to humanistic disciplines?

- What are some disciplinary intersections that have not been explored for lack of suitable starting points of commonality?

- Where is pattern-discovery most valuable?

- How do we formulate large problems with non-textual media?

I also offered some pie-in-the-sky ideas to jumpstart discussion, all completely personal fantasy projects. What if we …

- Perform an analysis of the entire English literary canon looking for rivers of influence and pools of plagiarism. (Literary forensics on steroids.)

- Map global linguistic “mutation” and migration to our knowledge of genetic variation and dispersal. (That’s right, get all language geek on the Genographic project!)

- Analyze all French paintings ever made for commonalities of approach, color, subject, object sizes.

- Map all the paintings in a given collection (or country) to their real world inspirations (Giverny, etc.) and provided ways to slice that up over time.

- Analyze imagery from of satellite photos of the jungles of southeast Asia to try to discover ancient structures covered by overgrowth.

- Determine the exact order of Plato’s dialogues by analyzing all the translations and “originals” for patterns of language use.

(Due credit for the last four of these go to Don Turnbull, a moonlighting humanist and fully-accredited nerd.)

Discussion swirled around but landed on two major topics both having to do with the relative unavailability of ready-to-process data in the humanities (compared to that in the sciences). Some noted that their own data sets were, at maximum, a few dozen gigabytes. Not exactly something you need a supercomputer for. The question I posed — where is the data? — was always in service of another goal, doing something with it.

But we soon realized that we were getting ahead of ourselves. Perhaps the very problem that massive processing power could solve was getting the data into a usable form in the first place.

The Great Library of the Jedi, Coruscant

At present it seems to me — I don’t speak for IBM here — that the biggest single problem we can solve with the grid in the humanities isn’t discipline-specific (yet), but is in taking digital-but-unstructured data and making it useful. OCR is one way, musical notation recognition and semantic tagging of visual art are others — basically any form of un-described data that can be given structure through analysis is promising. If the scope were large enough this would be a stunning contribution to scholars and ultimately to humanitiy.

The possibilities make me giddy. Supercomputer-grade OCR married to 400,000 volunteer humans (the owners/users of the million devices hooked to the grid) who might be enjoined to correct OCR errors, reCAPTCHA-style. Wetware meets hardware, falls in love, discuses poetry.

The other topic generating much discussion was grid-as-a-service. That is, using the grid not for a single project but for a bunch of smaller, humanities-related projects, divorcing the code that runs a project from the content that a scholar could load into it. You’d still need some sort of vetting process for the data that got loaded onto people’s machines, but individual scholars would not have to worry about whether their project was supercomputer-caliber or what program they would need to run. In a word, a service.

Who knows if either of these will happen. It’s time now to noodle on things. As always, if you have ideas for how you might use a humanitarian grid to solve a problem in arts or culture, drop a line. We’re open to anything at this point.

A few months ago Wired proclaimed The End of Theory, basically noting that more and more science is not being done in the classical hypothesize-model-test mode. This they claim is because we now have access to such large data sets and such powerful tools for recognizing patterns that there’s no need to form models beforehand.

This has not happened in arts and culture (and you can argue that Wired overstated the magnitude of the shift even in the sciences). But I have to believe that access to high performance computing will change the way insight is derived in the study of the humanities.

Evolving my music genome

So, iTunes Genius feature, it’s just you and me. Face-to-face. Gloves off. You think you know what I like? OK, you get one track to prove yourself.

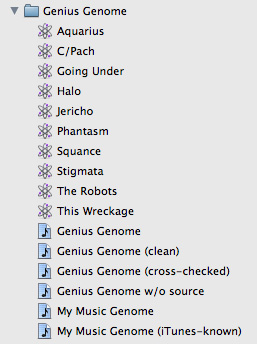

No, no, that’s not fair. I’ll give you something really juicy to crunch on. How about you take a playlist that I described a while back as My Music Genome, the very seed (in my human algorithm-based estimation) of the majority of what I listen to now? Musical eugenics.

Oh, you don’t make playlists from other playlists? Only single tracks? Sucks. Fine, let me do this one-by-one. 12 tracks in the list; 25 recommendations per track. Let’s start being genius … Go!

Wait, what’s that? You can only identify 10 of 12 songs in my genome? You’re telling me that you have never heard of Orbital’s Impact or Vapourspace’s magnum opus? You have the Orbital track in your music store, for god’s sake!

OK, fine, go for it with the remaining 10. I’ll wait.

- Going Under – Devo

- The Robots – Kraftwerk

- This Wreckage – Gary Numan

- Squance – Plaid

- Halo – Depeche Mode

- Jericho – The Prodigy

- C/Pach – Autechre

- Stigmata – Ministry

- Aquarius – Boards of Canada

- Phantasm – Biosphere

- Gravitational Arch of 10 – Vapourspace

- Impact (The Earth Is Burning) – Orbital

Cool, 10 new playlists. Let me open them right up. 250 tracks. Subtract the “source” tracks, that gives me 240 songs that you think spring from my base musical tastes. Interesting.

——–

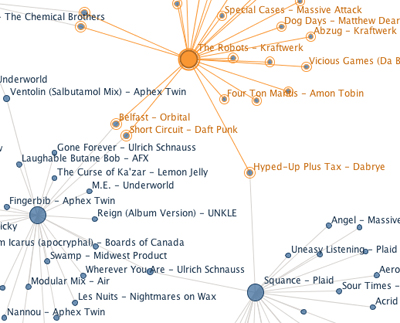

There are plenty of ways I could slice this data — Last.fm tags, AllMusic moods, BPM, waveforms — and I just might. But right now what jumps out at me are the duplicates. That is, the recommendations that come from two or more “source” songs from my genome. This might mean something.

The duplicates are important because they narrow the tree back down. They’re the inbred family members, points where multiple threads of interest converge. (In the image above, Hyped-Up Plus Tax by Dabrye, for instance, is a recommendation generated from both Plaid’s Squance and Kraftwerk’s The Robots.)

The overlaps are few, but meaningful.

- Aftermath – Tricky

- Children Talking – AFX

- Chime – Orbital

- The Curse of Ka’zar – Lemon Jelly

- Dominator [Joey Beltram Mix] – Human Resource

- A Forest [Tree Mix] – The Cure

- Future Proof – Massive Attack

- Gone Forever – Ulrich Schnauss

- Hyped-Up Plus Tax – Dabrye

- Laughable Butane Bob – AFX

- Little Fluffy Clouds – The Orb

- Me? I Disconnect From You – Gary Numan + Tubeway Army

- Mindphaser – Front Line Assembly

- Monkey Gone to Heaven – Pixies

- Paris – MSTRKRFT

- Satellite Anthem Icarus (apocryphal) – Boards of Canada

- Stars – Ulrich Schnauss

- We Are Glass – Gary Numan

A few identifiable strains emerge from this new “evolved” playlist. (These characteristics don’t necessarily reflect the dominant style of the artists themselves, just the tracks, which is more precise anyway.)

- shoe-gazy, downtempo: The Cure, Ulrich Schnauss, Boards of Canada, Dabrye

- hard-edged: AFX (aka Aphex Twin), Human Resource, Front Line Assembly, Pixies, MSTRKKRFT

- genre-benders: Tricky, Lemon Jelly, The Orb

(Not sure where Gary Numan fits in that typology, but he deserves to be in every list as far as I am concerned.)

Wow, John, that’s amazing, you’re thinking. You’ve managed to waste countless hours compiling data to tell yourself that you like soft music, hard music, and music that mixes the two. Such insight!

Actually it is interesting because the artists in this new playlist are some of my most-played. Lemon Jelly, Ulrich Schnauss, and Boards of Canada have been on heavy rotation for years. Clearly they are the fruit of stylistic seeds planted long ago. And now we have something approaching empirical proof. Truth is, most of what I listen to is either ambient or hard-edged or some outlying miscegenation. And there’s plenty of music that doesn’t fall into those categories.

The most interesting data point is that Satellite Anthem Icarus by Boards of Canada is the song that the iTunes Genius most thinks defines my music listening. It is part of multiple playlists generated from the source playlist.

Satellite Anthem Icarus – Boards of Canada

But here’s the crazy thing. That particular track is not the actual Boards of Canada track by the same name. It was included in a partially-bogus torrent download just prior to the official album being released. But I did actually fall in love with it. It is one of my favorite of their tracks. Except that it isn’t theirs. (Full story of this odd situation here.)

So, according to iTunes, the song that most represents the evolution of my musical taste is one that it should by all rights not even know about.

Now this gets to the heart of the mystery surrounding the Genius functionality itself. What exactly is it doing? It recommended this fake song to me which is neither named precisely what the real track is (in my library I have “(apocryphal)” in the title) nor is it the same length. And if by some crazy chance Apple is doing waveform analysis, it sounds nothing like the real version. So how could Genius recommend something that’s iTMS obviously doesn’t have in its library? Related, why would Genius not recognize the Orbital track in my library when I renamed it precisely as it is named in iTMS?

UPDATE: Commenter Pedro helpfully notes that this “fake” is actually Up the Coast by Freescha. Which makes this whole experiment really interesting. I agree with Apple that this song is extremely emblematic of my distilled music tastes, yet as noted above none of the metadata I had would have informed Apple to that. Is it possible that Apple is actually doing music analysis in the manner of Amazon’s text analysis? I really can’t believe that if for no other reason than that the initial Genius scan (when you run 8.0 for the first time) would take forever, which it did not. Still I want to believe. This is the way recommendations should happen.

I really don’t know how the recommendations are being generated, but I do think it is based on something more than store purchase data. Consider the jump from Ministry’s Stigmata to TMBG’s Ana Ng.

Stigmata – Ministry

Ana Ng – They Might Be Giants

There’s pretty much nothing similar between industrial music and irony-laden pop. But these two songs are definitely related when you consider their respective “hooks”: both use heavily-produced, effected, and clipped guitar noises as their main musical trope. Coincidence? Maybe, but why else would they be connected? Not music store data, methinks. Obviously Apple’s exact algorithm is a secret, but I’d love to know more.

——–

Some procedural notes. It helped that I already had a short playlist of stuff I considered influential. (Though I find it a lamentable shortcoming that Genius can’t generate a playlist from a playlist. It would have to infer commonality first then generate a new list. How tasty would that be?)

I then just set Genius to create a new playlist per track. Various recombinations of the playlists yielded a clean list which I flipped into a spreadsheet using the very handy Export Selected Song List AppleScript.

From the spreadsheet data I experimented with and aborted a bunch of different visualization ideas. At one point I had a monstrously large 10-headed Venn diagram in Illustrator that hurt to look at.

Eventually I created the network diagram in the screenshot at the top of this post using the wonderful Many Eyes social visualization site. (Yes, Many Eyes is IBM. Disclose that!)

A fuller, more interactive version of this visualization is available (Safari recommended, if you are on a Mac). Also the source data is there for the playing. I am sure there are other ways to massage it.

Enjoy this level of music nerdery? Dive into the Ascent Stage back catalog:

Forbidden City: Revealed on the History Channel

The street level outer wall of Tribune Tower in Chicago has all kinds of masonry and architectural adornment embedded in it from famous places around the world. A bit of the Taj Mahal, a sliver of the Parthenon, a brick or two from The Alamo, a chunk of the Berlin Wall, etc. It’s historical bricolage, literally. And a little odd, too — a sidewalk cabinet of curiosities composed of loot from Tribune reporters on foreign assignments.

I get it, though. Make the foreign and faraway more accessible, touchable. A proxy for tourism.

Now get ready, dear readers, for this is where I make the jump between two seemingly unrelated topics and in doing so stun you momentarily into forgetting how ham-handed the juxtaposition is.

There’s a better way. On October 10, IBM and the Palace Museum will launch The Forbidden City: Beyond Space and Time, a multi-user, immersive, three-dimensional virtual world recreation of China’s imperial palace. It won’t give you the feel of cold rock (or the microbial film of a thousand tourist fingers), but it is very much related to the desire to reach out and encounter the exotic in an embodied way.

If you prefer old-fashioned coach potato-variety virtual tourism, consider tuning in to the History Channel this Sunday, Sept. 21* for the premiere of its documentary on the Beyond Space and Time project. The show is the parallel story of the building of the palace and its virtual re-building, the latter explicating the former. It’s an interesting lens through which to look at a place: architecture as socio-history.

Plus, I’m in it. So there’s bound to be unintentional humor, if not outright farce.

Forbidden City: Revealed

History Channel

Sunday, Sept. 21

7:00 PM ET

* This airdate is US only. History International will broadcast the show at 9:00 PM ET on Wednesday, Sept. 24. Other international airdates to follow.

UPDATE: The virtual world is live and can be found at www.beyondspaceandtime.org.

But most of all, I missed YOU

I’ve been home from Africa just under a month. Thought I’d compile a list of things I miss and things I don’t.

Things I Miss:

- The Ghanaian handshake – Slap your hands together loudly (not a high five, just an aggressive bringing together of the hands for a normal handshake), hold until its a little awkward, then pull apart with a snap. I never quite got it and always felt horribly unhip trying to pull it off. But it was cool to be greeted like that.

- Laundered shoelaces – There was no laundromat nearby so we had some sketchy service that would come into our rooms and look for anything dirty. Before I figured this racket out they actually unlaced my running shoes (reddened by clay from dirt roads) and washed them separately. Anything for the upcharge, I suppose, though it was nice to have such gleaming white laces.

- Having taxis hail me – You never have to wave a cab down in Ghana, especially if you’re white. No matter where you are or how little you look like you need a ride, dozens of taxis will beep-beep beep-beep until you demonstrably tell them to go away.

- Saying “Ougadougou choo choo” – Ougadougou (wah·gah·DOO·goo) is the capital of Burkina Faso, the country to Ghana’s north. It is also the world capital with the most vowels in it. (Take that, Bosnia!) The nickname of the train service in and out of the capital is perhaps the most fun thing to say since I learned “trabajaba” in high school Spanish.

- Rear window car signage and business names – For reasons I still don’t completely understand Ghanaians are obsessed with naming their cars and shops with unintentionally humorous phrases from the bible. Or from something that sounds scriptural. Or not. “Be Holy Electrical Works”, “Dr. Jesus”, “I came naked”, “It wasn’t me”.

- Our prison economy – There were 10 of us at the guest house and we had only what we shlepped from home. Inevitably people forgot things and/or had items to swap. Though the Ghanaian markets offered lots of goods, there were certain things (meds, amenities, candy) that we had to barter amongst ourselves. It became a prison economy where mosquito wipes and vodka, rather than smokes, served as coins-of-the-realm.

- Dial-a-proverb – Emerson said “language is fossil poetry” which is a pretty accurate description of how laden the Twi language is with poeticisms and figures of speech. In fact, formal conversation consists of little but such turns of phrase. My interest in this characteristic of Twi became a game with my friend Yaw who would take any situation I gave him, call his pal who’s a master of Ghanaian proverbs, and come back with an appropriate phrase for the occasion.

Things I Do Not Miss:

- Restaurant service – No matter where we went, city or village, Italian, Chinese, Lebanese or Ghanaian, all meals took at least two hours. Even when we thought we were being sly by calling in our orders, the service was atrocious. We think this was because of limited staff and the fact that everything was made basically from scratch as soon as it was ordered. There were never enough menus to cover the table and food was never brought to us even near the same time. Often people were served thirty minutes after others. The food, however, was almost always exceptional.

- The Ghanaian noise for getting one’s attention – I understand that this is a perfect example of clashing cultural habits, but the staccato hiss that Ghanaian’s use to hail someone is just poison to Western ears. It sounds like a curse or worse, though admittedly it does get your attention.

- Lack of currency – Last year Ghana re-denominated its currency such that 10,000 old cedis would be equal to one new cedi. There were many reasons for this, but most signage has not caught up. That’s a surmountable, calculable inconvenience, but the reality is that no one ever has change. Hacking off four zeros means no one has the sub-cedi currency known as the pesewa. Merchants can’t break even small bills. I can’t tell you how many times I simply walked away either without the good I wanted or having given the merchant a sizable “tip”.

- Instant coffee – ’nuff said.

- Compact fluorescent bulbs – Don’t get me wrong. I’m all in favor of CFL’s, but Ghana has adopted them in a huge way. I don’t think I saw an incandescent the whole time I was there — which itself is fine, but CFL’s have indiscriminately and nakedly replaced every bulb everywhere. There’s nothing less comforting that a bright, uncovered fluorescent bulb. To make the switch, in my opinion, requires not just environmental consciousness but also some stylistic consideration.

- Racist South Africans – I met three white South Africans while I was in Ghana. The first was a racist drunk at a local Internet cafe who obsessively gambled online while smoking a hookah pipe. One night he was too drunk to realize that a shisha coal had fallen onto his laptop power supply. BOOM! It was like someone detonated a small firework. But he kept gambling on battery power. The second was a chatty guy at a hotel I was staying at in Accra. He would not take any hint that we did not want to talk to him at breakfast and insisted on letting us know his impressions of Ghanaians, this being his first visit. Let’s just say he used the word “savage” frequently. The third was a very pleasant, younger guy on his own on a business trip who made it clear that not all white South Africans harbor such deep-seated racism. I’m glad I met him.

- Dirt roads – My ass and nerves will never be the same. See the first part of this post.

- Diet Coke false advertising – Called Coke Light in Ghana, Diet Coke is obviously the focus of a massive marketing campaign. Billboards and signage are everywhere. And yet, no one ever has it in stock. It is a mythical elixir, something promoted but never distributed. My colleagues made fun of me for continuing to ask for it after a dozen failures, but by then it was a matter of principle.

- Under-table space management – We often ate out in relatively large groups. This required restaurants to push tables together. Inevitably seats would be placed right at the junction of two tables where no two legs could ever go. We saw this everywhere. It was almost as if the ability to arrange a table with chairs around it were more important than actually seating people there.

And yet, those cons are not nearly enough to make me not want to get back as soon as possible.

1¢ stage … huh?

Seems like there are more first-time visitors to my humble blog than there used to be. This might be a function of my linking Twitter updates to Facebook status, which if you do the math means that a lot of non-geek acquaintances are now alighting on Ascent Stage without a clue in the world what the hell is going on. Welcome, dearest friends!

Thought I’d take a brief moment to explain the name of the blog, something I’ve never rightly done.

You get some hilarious pronunciations and questions, especially when trying to give out the URL over the phone in an interview, say. “A cent, as in one penny?” “Ascent’s ‘tage, like Hermitage?” “Nascent Stage, you mean like an infant?” “ASS-ent stage, what is this porn?”

Simply, an ascent stage is the part of the rocket that goes up as opposed to being the one that breaks for going down. Sadly, in the post-Apollo era this has mostly been the only stage a rocket has. We ain’t landing anywhere with a rocket as long as we have a Shuttle.

Ascent stage refers usually to the upper half of the lunar modules that we put on the moon. The descent stage landed the astronauts (counteracting the moon’s weak gravity); the ascent stage put them back up to link with the Service Module whose rocket would take them home. Simple enough.

But why the name? What I’ve always liked about the concept of an ascent stage (in addition to the space dorkiness) is that it implies progress, upward motion, forward movement. But also a discrete point in time, or phase. There’s also something very slightly sad about it too, because to ascend means you descended at some point and you’re leaving something behind. (In the Apollo case this was the descent stage itself.)

There’s a classic image from the last Apollo mission where they left a camera specifically poised to capture the ascent back up to the orbiting command module — something which had not been done on previous missions. Not sure what it is but there’s something eerie and solemn about the footage that was captured. Two guys in a rickety polygon blasting off from a much more stable looking bottom half, which is now left to decay on the moon forever.

So, that’s kinda the rationale or feeling behind the name itself: progress, ascendancy, upward motion … tinged with mystery, loss, even desolation. My blog.

By the way, I’m considering a redesign. Input welcome. Via CAPCOM, naturally.

iPhone apps and Flickr nit-picking

The iPhone 3G and firmware 2.0 were released hours after my plane departed for Africa. It was source of great consternation for me, but it did force a kind of critical distance that I rarely have from new technology releases. What did I learn? I learned that I don’t care for critical distance from new technology releases.

I did eventually get to update the firmware on my original iPhone while I was over there, though there was virtually nothing I could do with new apps without good network access. Read: all the battery-sucking issues, none of the benefits. Since I have been back I’ve gotten a 3G, ceding the original phone to my wife who really needed it.

Here’s a list of apps that I’m liking a great deal.

- AirMe – Takes photos and uploads them automatically to Flickr with geo info (and weather tags, if you want). Works with Facebook too. Here’s a sample photo.

- Last.fm – Last.fm has always been great, but conceptually is so well-suited to a mobile device. No background apps on the iPhone means it won’t play while you do other stuff (ala the iPod), but them’s the breaks with Apple.

- MLB.com At Bat – Recently updated to include field and batter infographic overviews. Very well-designed and pretty timely video clip access make this indispensable, even when you’re at the game (especially so at Jumbotron-less Wrigley).

- Remote – Possibly the most useful app out there, which is probably why Apple got to it first. Creates a slick remote interface for iTunes and Apple TV’s on your LAN.

- Rotary Dialer – Because you can, that’s why.

- Shazam – Too-good-to-be-true app that identifies the title and artist of a currently-playing music source (like the jukebox at a bar). Pretty damn accurate and it offers instant links to buy the track. Great party trick potential trying to stump it.

- Simplify Media – Sets up a server on your machine that allows streaming access to your iTunes library wherever you (or anyone you permit) happen to be. This was cool when it was computer-to-computer, but the ability to stream anything from home to your iPhone is game-changing. Points to a day when the iPod has no storage at all and is just a thin network interface to your cloud of media. Highly recommended.

- Tetris – Slower to start than the free knock-off (now removed) Tris, but still mesmerizingly addictive. Takes a while to get used to manipulating blocks by finger flick.

- Twitterific – Not sure I’d even use Twitter if not for the desktop app Twitterific. The iPhone version is just as scrumptious, adding in some location features to boot.

There are a few apps I want to like, but just don’t. NetNewsWire is everything I want in an offline feedreader (with desktop and web synching!), but it is just dog-slow. Takes forever to load my feeds. AIM works fine, but instant messaging just doesn’t work with the no background app paradigm. You can’t give all your focus to chat.

And here are the apps I wish existed.

Backpack – I know 37Signals is all about lightweight web apps, but what I would love is actual offline access with synch.

SMS over IP – We can make phone calls with VOIP, but why not SMS? This may exist and I don’t know it, but with AT&T’s ridiculous messaging fees, why put anything over the voice network you don’t have to?

MarsEdit – On-the-go blog composition. Synching with desktop drafts would be yummy.

A native NPR app.

Google Earth – Why not? The video capabilities are clearly adequate and with the iPhone location abilities seems like a natural.

A great e-reader app. Kindle-screen quality with iTunes store breadth of access? Sign me up.

A stickie note app that synchs at least to a desktop app, preferably to a web app too. Most text pad apps for iPhone do too little (see all the to do list apps in the App Store) or too much (like Evernote, which I tried desperately to like). All I need is stickie notes. ShifD is promising, but right now you can only get it on your phone as a web app. Not ideal at all. If you know of something along these lines, please let me know!

———-

In other news, I’ve been using Flickr a ton lately. The more I use Flickr the more I love it, but it has prompted some critical observations:

- Video on Flickr is fantastic, but none of the video metadata comes over. This may not be Flickr’s fault, but it breaks the videos-are-just-long-photos thing organizationally.

- There is a “Replace this photo” option for stills that is very handy when uploading high-res versions of low-res originals. But this function does not exist for video. You have to delete and re-upload, losing all metadata and comments. Boo.

- Speaking of replacing, it would be great if there were a bulk replace function. Having to do it photo by photo is so … unFlickr.

- Flickr slideshows do not include video. C’mon!

- FlickrExport for iPhoto is indispensable, but it does not allow permission-setting (CC, etc). This is a very correctible limitation, it seems to me. (There’s a Facebook export from iPhoto that works just as smoothly).

- Speaking of iPhoto, why will it not copy video seen from a shared library like it will photos? Annoying!

Phew. Feels good to release some geek.

Slave to the cliché

Recently I’ve had occasion to reflect on the awful state of presentations. You see them all the time — in meetings, at conferences, shunted around via e-mail — and they sap the soul.

There are many aspects of crappy presentations, but I’ll focus here on only one.

From Wikipedia:

“Shave and a Haircut” featured in many early cartoons, played on things varying from car horns to window shutters banging in the wind. Decades later, the couplet became a plot device in the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit, the idea being that Toons cannot resist obeying cartoon conventions. Judge Doom uses this to lure Roger Rabbit out of hiding at the Terminal Bar by circling the room and tapping out the five beats on the walls.

Here’s the scene from the film:

In film there’s a term called “mickey mousing” which refers mostly derogatorily to the underscoring technique of using music to exactly ape what’s seen on screen. Early cinema used it all the time, as the medium was new and unexplored. Examples include playing a sea shanty when a ship floats into view or mimicking the slicing of Janet Leigh in the shower in Psycho.

As with any technique used smartly it had its place, but mickey mousing quickly devolved into caricature as a stock device in cartoons (hence the name). Music in cartoons, usually orchestral, almost always reinforces in the most literal way the action on screen. Which is fine, because cartoons are meant to be laughed at.

But most presentations are not meant to be laughed at — at least not all the way through — and this is a problem. The idea behind mickey mousing pervades most presentations. That is, presenters often attempt to reinforce what is being conveyed in one medium (usually bland bulleted text) with another (usually hideous clip art of illustration).

This is almost always a bad idea. And the reasons are many.

First, it distracts from the real message. Presentations should be about the presenter, not about what’s on screen. If there is an image on screen it should complement, even slightly modify what the speaker is saying, not mindlessly illustrate what the bullets say. (Which goes the same for the bullets too: if what you’re saying is on the screen why even present at all?)

Second, mickey mousing in presentations demeans the intelligence of your audience. Do you really need to put a clip art image of an airplane next to your point about airborne supply chain routes? Does this make your point more compelling? Might it not say something more about the point itself? Or your confidence in the point? Or maybe just your confidence as a presenter? Most audiences, if not snoozing, are smart enough to ask these questions themselves.

And sometimes bad graphics have much direr consequences.

There are plenty of resources out there to help you make a better presentation. If you want an example of an extraordinary interplay between what’s being said and what’s being shown, have a look at Dick Hardt’s Identity 2.0 talk from OSCON 2005.

My colleague Ian Smith has put together a great overview of strategies for making yours more persuasive and entertaining. Highly recommended.

Maybe the simplest piece of advice is to ask yourself, is my presentation a deliverable or a performance? That is, is it meant to be read, studied, and digested (a solitary activity) or is it meant to sketch broad themes to many people and connect the authority of the presenter with the validity of the material?

These two things — a document and a presentation — should almost never be the same thing. They can cover the same material, but throwing a presentation made for reading up on the screen is like projecting the score of a symphony in the orchestra hall in lieu of music.

Tom bo li de say de moi ya, yeah Jambo Jumbo!

At the end of my assignment in Ghana I took a short safari on the Masai Mara in southern Kenya. It was extraordinary.

But it was hell to get to in every conceivable way. First we waited for seven hours in a cramped, hot hovel of a concourse while unspecified repairs were made on our plane. By the time we boarded at 4 AM we were too out-of-our-minds tired to care what possible repair could take that long and not require a full cancellation.

Arriving so late in Kenya we had to high-tail it out of Nairobi to make it to the Mara by nightfall. I didn’t realize why this was such an issue, until shortly after entering the Rift Valley and saying goodbye to any semblance of paved roads. Our driver/guide would have been maniacal in any vehicle, but the one we were in was particularly death-trappy. The speedometer did not work and yet every single warning light on the dash was a constant glowing red. I suspect the speedometer had been disconnected to get around a governor that the minivan supposedly had installed by the tourist commission.

Kenyans jocularly refer to the bumps of riding on pothole-ridden dirt at breakneck speed as “an African massage”. Which was funny for, perhaps, 100 yards. And then night came and the animals with it. It was exciting to see a herd of zebra in the middle of the road. Exciting for a second before realizing that my first experience with a wild animal might involve it coming through the windshield in a bloody heap. We actually rear-ended a wildebeest at one point.

Ah, but it was all worth it. The safari itself was a relatively last-minute, budget affair after our official assignment. Yet we were right in the middle of what’s known as the Great Migration when millions of animals (and their predators) move from the savanna of the Masai Mara in Kenya to the Serengeti in Tanzania.

You see so many animals in such a natural state in such a small amount of time that you start to think it normal, say, to have a group of monkeys invade your tent and steal your food. (Which they did, the little bastards.) But then you realize it is normal. Humans are just used to zoos, and National Geographic, and urban life (mostly) devoid of wild game.

We saw zebra, impala, baboons, huge rabbits, bat-eared fox, grasscutters, wildebeest, Topi antelope, elephants, giraffe, vultures, hyland cattle, African buffalo, the rare black rhino, the secretary bird, vervet monkeys, Thompson’s gazelles, warthogs, ostriches, lions, hippos, mongooses, hyena, Marabou stork, eagles, guinea fowl, and one very elusive leopard.

Here are some glimpses from the full set of photos and video.

And now, the payoff. “Hello” in Swahili, the main language spoken in Kenya, is “Jambo!” which is a hell of a lot of fun to say. And it’s even more fun to say when you realize that it is what Lionel Richie was actually saying while rocking out during All Night Long. I can’t seem to find a translation of the full line (in this post’s title) so in the meanwhile, do yourself a favor and watch the video.

Africa is a way of thinking

I came to some startlingly common sense realizations while in Africa. For instance, its now clear to me that sustainable environment practices and Africa are inextricably linked. They aren’t separate matters or concerns or causes. To act on one is to act on the other.

Here’s the obvious part. Africa — and the entire “Global South,” as it is often called — stands to lose the most from planet-wide environmental deterioration. The fate of Africa has always firstly been tied to the environment. Even when you subtract out all the man-made horrors that Africa has seen life on the continent is shaped in deep ways by the ecological, geological, and meteorological hand it has been dealt. Subsistence agriculture, wars over limited (or precious) resources, lack of access to coasts, the range of the tsetse fly — all these things define life more immediately than the environment does (for now) in other places.

But there was insight too. A lesson, you could say, that the first world can learn from the third. Sustainability is a way of life for Africans. They don’t think about it as such. It isn’t a campaign or a movement like it has become in the West, but it is evident everywhere, woven into everything Africans do.

Simply put, Africans live with resource scarcity. They have not experienced consumption out of whack with production because it has never been a possibility.

For every place you see selling cars you see five places recycling every possible component of the cars. Usually its for repair, sometimes it is to create something utterly different.

Or take tro-tros, the ubiquitous, horn-happy minivans that criss-cross every part of Ghana moving people more efficiently than a bus system every could. It’s a totally decentralized, mostly private group taxi service. Mass transit on an unbelievable scale with no set routes at all. Need a ride? Flag a tro-tro. You’ll get where you’re going. (Not unlike hailing a “taxi” in Russia, though there rides are less frequent, less capacious.) While tro-tros are almost universally decrepit, smoke-belching buckets of bolts, the system as a whole is by far more environmentally friendly than private cars or even a fleet of taxis.

One fact of life in Ghana is the unreliability of centralized services. The electricity grid, for example, cuts out a few times every week. Just … off. Usually mid-day when it is hottest out. Yet this is not nearly as disruptive as it would be in the West. Partially this is just an attitude of resignation; that’s just the way it is. But because it’s the norm most places simply do it themselves with generators on standby (or have ways of manually doing what would otherwise be electrically-powered).

There’s no central water supply either so in urban areas private gravity tanks (or nearby streams) provide running water. The explosive growth of mobile phones is in part fueled by a lack of reliance on a centralized grid of services. It’s obviously not industrial age mega-infrastructure but more like modular, emergent services — build as you go, bottom-up. Like the Internet itself, basic services are built to work around outages.

To a Westerner this seems like privation but, looked at another way, it is a built-in constraint on excess usage. Self-sufficiency isn’t radical; it’s practical. And self-sufficiency naturally requires an intimate knowledge of one’s own patterns of consumption. You use what you have and nothing more. It ain’t rocket science.

So why is this a lesson? Certainly I’m not claiming that open sewers or power outages are the way forward. Nor should it be taken to mean that Africans are somehow immune to over-exploitation of resources.

Yet, Africa provides an example of what a society might look like that has so totally internalized sustainable living that it informs everything it does. Africa as a behavioral template, not a developmental one.

There are many paths that lead to this way of living within one’s means. You can choose to do it or you can be forced to because all your other options have been exhausted. Most of Africa has no other choice.

It took me a while to realize how pragmatic the idiosyncrasies of daily life are in Ghana. After first I thought the army of vendors on the road was a nuisance. They’re not “roadside” but in the middle of the road, often long lines of people selling the exact same thing — tissues, water, power strips, mangos, anything. (Even the mayor wants them off the road.)

But actually it makes a ton of sense because traffic is often such a mess. It’s like one huge drive-through mall. In the lingo of a typical consultant: they’ve monetized gridlock. It’s efficient and practical, such as at the toll stop pictured above. I’m not arguing for in-road vending so much as noting that what seems crude is often entirely sensible, bordering on ingenious.

It’s hard for non-Ghanaians not to do a double-take when they see women carrying staggering loads on their heads, but once the shock wears off you realize, wow, that really is efficient. The arms are free to do other things while the entire frame of the body distributes the load atop the spinal column. Also, it makes for good posture.

But the most practical form of carriage is the way babies are swaddled. Just a single sheet wrapped around the child who’s straddling the mother’s back and literally sitting atop her butt. I never once saw a child squirming or screaming and the moms looked similarly non-plussed. Again, the arms are free to do whatever.

What do baby swaddling and sustainable living have to do with one another? They’re both examples of deep-rooted pragmatism. It seems simple, even backwards sometimes, but the way of life I saw both in Ghana and Kenya was firstly about solving everyday problems. It’s largely coincidental that many of these problems are matters of production and consumption — the very basis on our misaligned relationship with the planet.

Let’s take some inspiration from Africa. It’s a plentiful, renewable resource, after all.

A workshop on high performance computing in the humanities

A few years back I mused, where are the humanities applications for supercomputing? Well, we’re going to try to answer that.

Announcing a special one-day workshop to brainstorm uses of high performance computing in arts, culture, and the humanities. If this is your thing, please consider attending and/or passing it on.

A Workshop on Humanities Applications for the World Community Grid

On October 6, 2008, IBM will be sponsoring a free one-day workshop in Washington, DC on high performance computing for humanities and social science research.

This workshop is aimed at digital humanities scholars, computer scientists working on humanities applications, library information professionals, and others who are involved in humanities and social science research using large digital datasets. The session will be hosted by IBM computer scientists who will conduct a hands-on session describing how high performance computing systems like IBM’s World Community Grid can be used for humanities research.

The workshop is intended to be much more than just a high-level introduction. There will be numerous technical demonstrations and opportunities for participants to discuss potential HPC projects. Topics will include: how to parallelize your code; useful tools and utilities; data storage and access; and a technical overview of the World Community Grid architecture.

Brett Bobley and Peter Losin from the Office of Digital Humanities at the National Endowment for the Humanities have been invited to discuss some of the NEH’s grant opportunities for humanities projects involving high performance computing.

If attendees are already involved in projects that involve heavy computation, they are encouraged to bring sample code, data, and outputs so that they can speak with IBM scientists about potential next steps for taking advantage of high performance computing. While the demonstrations will be using the World Community Grid, our hope is that attendees will learn valuable information that could also be applied to other HPC platforms.

The workshop will be held from 10 AM – 3 PM on October 6, 2008 at the IBM Institute for Electronic Government at 1301 K Street, NW, Washington, DC. To register, please contact Sherry Swick. Available spaces will be filled on a first-come, first served basis.