A little bit about Ghana

The more you know …

Ghana, formerly known as the Gold Coast, was the first nation in Africa to receive independence from colonial rule in 1957.

Accra, Ghana, capital of the country, is a sister city of Chicago, USA.

There is no place on Earth you can travel to and require more vaccinations than coastal West Africa.

Ghana is the size of the US state of Oregon (roughly 92,000 miles2).

The name Ghana refers to the ancient empire of Ghana located in Senegal, Mauritania, and Mali with no overlap whatsoever to the current geographical boundaries of the country.

Ghana is the country closest to the center of the globe, as defined by international measurement. The prime meridian runs through it and the equator is only a few degrees south of the coast.

An amazing amount of the world’s scrap electronics end up in Ghana for precious metal recycling.

This is the Cicero Guest House, where I will be staying. It ain’t the Four Seasons, but I’m not complaining.

So that’s it for posts pre-departure — maybe until Aug. 15 given connectivity, but I doubt it. I’ll be chronicling the adventure here (much as I did in Italy exactly one year ago) and on the newly-launched official IBM Corporate Service Corps blog.

Thanks to everyone for the well wishes, offers to assist with the family while I am gone, and claims on my personal items should I not return.

Calligraphing beyond space and time

All this talk about Ghana you’d think I wasn’t on the cusp of launching the biggest project of my career. The virtual world recreation of the Forbidden City in Beijing, known as Beyond Space and Time, is made public on Sept. 17. Right now we’re in the final stretch of feature implementation, content loading, stress testing, and general cleanup.

One of the many small joys of the project has been meeting Wendy Wu, a friend of a project team member who is also an accomplished calligrapher. A few years back she designed the first project logo, a calligraphed depiction of the words “beyond space and time” which, in Chinese, is a phrase used to convey something superlative or exceptional. Of course, it is also an apt description of a virtual world in English.

Yesterday on a trip through Chicago Wendy was kind enough to offer a demonstration of her calligraphy technique. I’ve sped up a video of her in action — mostly to come in under Flickr’s 90 second limitation — but even in fast-motion you can see how deliberate and fluid the strokes are. Truly a wonder to watch.

A few photos here.

Offline dance

We’ve been told there’s no Internet at the hotel in Kumasi (though an unsubstantiated report says the proprietor is “working on it”). The program manager has earnestly stood by his directive that we should experience the Internet the way Ghanaians do, which is to say (if they do at all) at public cafes.

I see the point. You can’t consult much less design for a culture whose particular constraints you do not understand. OK. But this my biggest concern since, as a team with a job to do involving (at least in my particular task) using the Internet as a route to market, this seems like an unfortunate and avoidable self-limitation.

But so it is. To make matters more challenging, we’re told that power cuts out in Kumasi two to three times a day. Many places have backup generators; many do not. So, you can imagine the near-panic I’m in being a creature of connectivity. I’m not proud of it, just laying it out truthfully.

It’s a reversal of the productivity direction I’ve been working towards for years: a near-total online workflow. Sure, I use desktop apps and love a few dearly. But they’re almost all hooked to networked data and have a web-based interface too. Most simply won’t work without a connection. My laptop is about to become an island.

Thinking through how it will actually work has been interesting, though. There are three scenarios, not counting the pipe dream of guest house Internet:

- Connection at place of work, relatively nearby Internet cafe

- No connection or very limited connection

- Machine failure

The first is the most likely, though it still involves long offline periods. It’s pretty easy really: e-mail gets pulled into Mail.app and calendar items into iCal whenever I can connect. NetNewsWire can suck down feeds for offline review.

But that leaves Backpack and Basecamp, two online services I use for personal and project task management. There’s a great offline synch app for Backpack called Packrat, but for Basecamp I’m basically hosed. In a stroke of great timing, my files at Google Docs now live offline thanks to the Google Gears integration it now offers. I compose blog posts in the superb MarsEdit so that’s not a worry. I suppose there are some offline Flickr apps, but that seems like such a hassle. IM, Twitter, virtual worlds: forget about it.

The second scenario is basically the same, only more dire. I suspect I will just abandon e-mail altogether and just compose offline blog posts hoping to cast their bottles into the sea at some point.

The last scenario — total computer death — had me considering bringing two laptops … until the sheer idiocy of hauling all that hardware to Africa brought me to my senses. (Some of my teammates are considering not even bringing one. What!?) When you consider that the closest Apple Store is half a continent and a sea away, you basically realize that letting go is easier than fighting it. If the MBP dies, my hipster PDA takes over.

If this particular calamity should come to pass I’ve loaded up a USB key with a bunch of portable apps so that I can at least fake the semblance of a personalized workspace at a public terminal. Loading critical data onto the key just isn’t practical, though, so I’ll basically be all dressed up with no place to go.

And yet. There’s an upside to these scenarios. There are still a few apps that require no connection at all. In fact, the distractions of the ‘tubes are actually a hindrance to using them in some ways. I’m thinking specifically of Ableton Live, but also tools like Tinderbox and Scrivener. All these are for personal composition. I can imagine being hunched monk-like in my room hammering out new tunes and chapters, perversely thankful for the isolation.

That is, if the electricity stays on. There are as yet no affordable (or compact) solar-powered solutions for laptop power. So, I have my three MBP batteries.

Add to all this worry that the iPhone 2.0 update and 3G hardware is released the day after I leave and you may understand better why I am obsessing more about Internet withdrawal than microbe invasion.

If this sounds like spoiled geek whining, you’re probably right. But I think this post will be a useful record to return to when the real conditions of daily work present themselves. I’m pretty sure I’m being shortsighted. Which is probably a good summary of my overall preparedness for this adventure.

Not too long now. Departure Thursday.

Brambleberry, the tasting

Last summer my boys and I plucked wild raspberries from my parents’ home in Galena, Illinois. We brewed it into a wine that became part of our giftbag for our annual Christmas Party. It looked beautiful, festive. People were very pleased.

That is, until a few weeks post-bottling when all the gift bottles were in various homes and started spontaneously uncorking, spewing red hooch all over living rooms, cellars, and kitchens. Yep, we gave timebombs as our Christmas gift. (Turns out the right-before-bottling sweetening that the recipe called for restarted some latent, mutant yeasties in the bottles, damnit.)

Some bottles did not blow up, however, including my sole bottle. I advised the attendees to wait until Spring to drink it. We waited a bit longer and drank it this weekend up in Galena, mere yards from where the berries were harvested.

The verdict … mild. Not nearly alcoholic enough, which you might take as a good thing, but it really lacks body. So it certainly won’t kill you (like the Applejack), but it isn’t all that great. Apologies to those expecting excellence. But it is homemade and it was made with love, so if it didn’t explode on you, do enjoy!

The Gigglesnort Hotel

In the ongoing quest to analyze my youth for clues to explain why I am the way I am, I think I’ve hit the motherlode.

The Gigglesnort Hotel was a children’s show of which I have only the vaguest memories, but they’re all dark. Which is odd for a kid show, no?

Gigglesnort is a cherished memory of anyone who grew up in the 70’s in Chicago. It was produced locally and its creator and lone human actor was Bill Jackson, something of an icon in Children’s TV here. But damn was it creepy. It was all puppets and, looking back on them now, I’m not surprised I think of it more in fear than in joy. Chucky would have been right at home in Jackson’s entourage.

The hotel was run by a senile admiral who stayed in the attic and thought the inn was a ship. He’d steer it at a captain’s wheel and request reports on the crew. A dragon — Dirty Dragon by name — ran the boiler in the basement, spewed smoke from his nose and was generally mean. I think he was also the mail man. There was a hotel employee named Weird who was exactly such, looking vaguely mentally addled (pictured above).

But the strangest character was a lump of clay named Blob that “spoke” in grunts and wheezes and basically sounded like a drunk old man. He was constantly being manhandled into new forms by BJ the clerk.

I suppose it all balances out with the Superfriends and The Bozo Show, but when I think about what I was watching in the 70’s — Land of the Lost, Son of Svengoolie, and Gigglesnort Hotel — I do wonder if my current viewing tastes would be, you know, less macabre.

Only one way to find out I guess. Gotta buy some Gigglesnort DVD’s and choose a control group from the kids.

Love of country

In late 2001 we were giddy with our first child. The fallen towers and clingy new parent syndrome had pretty much bivouacked us into our condo. The last thing we wanted to do was bring a stranger into the home to be a nanny.

We interviewed a couple of ladies, all eastern European as I recall. Nice enough, all capable of tending a baby, none capable of making us feel good about it. Then we were referred to Margaret Kumi, a classy, soft-spoken mother of many. She was from Ghana.

During the interview Margaret good-naturedly answered my silly list of questions. I remember asking what the first thing she would do if our baby got hurt. She didn’t really understand what I was asking, probably because it was a trick question, and the right answer was so damn obvious. I wanted her to say “I’d call you,” but of course the answer was (and is): make sure the kid’s alright. Later, after we easily hired her, I reflected on how much more that question said about me than her.

Margaret was our full-time nanny for almost five years. We welcomed her into our family and, surprisingly, she did the same for us. We came to know her children, her adopted children, her husband, and visiting relatives from Ghana. We were introduced to baby naming parties, the glutinous food known as fufu, and the sonorous language called Twi.

Her connections with Ghana were strong; most of her family still lived there and she returned twice while she was in our employ. When I was working in Egypt I thought often of making a side-trip to Ghana — a longer flight than cross-country US, but a side-trip in my mind. It never quite worked, mostly because it required a layover in some sketchy Nigerian refueling depot on the FAA might-not-wanna-go-there list.

When I was accepted into the IBM Corporate Service Corps the program manager asked me where I wanted to go and I immediately said Ghana. Margaret and her family were ecstatic. It was a unique moment. You might think this closed some sort of circle, a postmodern Roots with a twist. But it sure didn’t feel like that. It felt like a start — and the wheels I could surely see turning in Margaret’s head confirmed as much.

A few weeks later off the high of the acceptance, during one of our Sunday evening Twi lessons, Margaret and her husband told me that they wanted my help. They had been thinking for a while of returning to Ghana. The country was doing well relative to West Africa and even absolutely for sub-Saharan Africa. Margaret wanted to open a daycare center in Kumasi. She said they had been trying to figure out a way to get back to Ghana while I was there so I could, in her words, help her figure out how to do start a business there. My emotions at this time were a somewhat perfect balance of eagerness and bewilderment.

I am an African know-nothing. I’ve read a few thousands pages on the continent and its history, peoples, and business outlook since I was accepted into the program, but let’s be clear here: I don’t know the first thing about starting a business in the relatively comfortable nest of the USA let alone Ghana. But how could I say no? Margaret is a product of Ghana and her care for my kids derived from that.

There’s another thing though. This isn’t payback. My desire to help Margaret isn’t what many characterize as Western guilt about Africa. I have no colonialist baggage; I feel no latent pangs over the slave trade (though you might ask me again after I visit the Middle Passage embarkation points). It’s more personal than that. Margaret came to America for a better life, remitted part of her earnings to her family in Kumasi as best she could, and then, because of mature governance and a world eager to help, she’s now afforded an opportunity to return home. It’s rare and, though our lives will be the lesser if it happens, so very right.

Margaret told me last week that she’s secured a plane ticket and will be there when I am. I couldn’t be happier.

It’s an interesting thing to reflect on this July 4 weekend. I’m proud of my country — and my company — for putting me in a position to help.

Necessary feeding

Recently my subscription to Daring Fireball lapsed and it took me a day or two to realize that Gruber was not on vacation but that my feed had stopped. Sucked. Made me grumpy. Misanthropic, even.

So I figured now was a good time to comb through the ol’ reader and highlight those feeds that I can’t do without. I’m subscribed to hundreds of sites, but there are a few that give a moment of pleasure in simply seeing the new entry indicator in bold. Some of these are obvious and well-known, others perhaps not. Have a look at the one’s you don’t know.

Daily

Coudal Partners

Daring Fireball

Gapers Block

ISO50

kottke.org

Mark Bernstein

Not-so-daily, but just as satisfying

fueled by coffee dot com

microscopiq

PointAwayFromFace

Roo Reynolds

stevenberlinjohnson.com

wayne&wax

It’s interesting to think about what’s common about these sites. True, I know the authors of 7 of 12 of the blogs, but that’s not really an explanation. It’s that I feel a connection to all these sites in ways other than just being a reader.

For instance, I’m a huge fan of the music of Tycho (ISO50). I have eminent respect for the scholarship of Wayne Marshall (wayne&wax). Gruber (Daring Fireball) is a close friend of Jim Coudal’s; that’s a degree of separation that makes him almost a pal. And so on.

I’m sure there’ll be a blog one day from someone I have no other connection with, but right now it’s all about personal affinity. A kind of social networking informs my own reading habits, you could say.

Should I be following your site? Let me know.

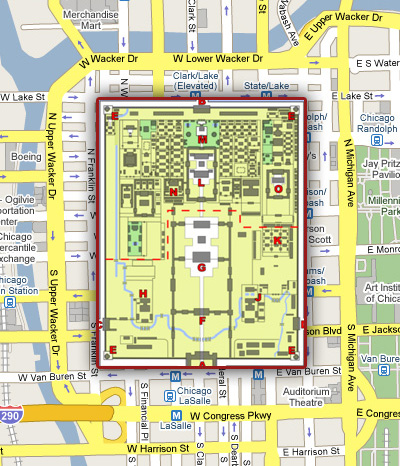

How big is the Forbidden City?

Jack Blanchard, long-time creative director colleague*, recently whipped up a map to answer a frequent question about the scale of the Forbidden City in Beijing. I suppose it isn’t all that helpful if you don’t know Chicago, but the short answer is: basically the size of the Loop.

You know, now that I look at it, if the mayor would only carve a canal to the lake along Harrison we could give the Loop a moat. Just need to build 30-foot-thick walls and put guard towers in and we’ll be all set. Just try to mount an attack, mongrel St. Louisans!

* Also impresario, dilettante, bon vivant, roustabout, part-time carnie, certified life coach, and TSA detainee.

Maine holiday

Just back from a first-ever trip to the coast of Maine. What an amazing place.

Couple of tips for the uninitiated. You’ll encounter lots of puns on the name “Maine”: Maine-ly Antiques, Maine Drag, The Maine Attraction. Avoid these at all costs. Also, an easy clue as to how greedily a place wants your tourist dollars is to note the amount of signage and text that spell things according to the Maine accent. If you see more than one reference to “lobstah, chowdah, and beeya” leave. Immediately. Lastly, if you hate the Red Sox do not visit Maine.

To boil down what Maine thinks it has to offer I present you with the following list:

- lobster

- blueberries

- moose

- the way life should be

- a carbonated beverage called Moxie

- lighthouses

- puns on the state name

But it is really so much more than that. Have a look.

Testing 1-2-3

Coudal Partners has released it’s third edition of Field-Tested Books. It’s a stunner.

FTB is a collection of short reviews that explores the connection between the subject of a book and the actual location it was read. Like Rob Gordon’s autobiographical organization of his record collection in High Fidelity, the idea is that reading is not a act sliced off from the context in which it happens. The real world has a way of bleeding into the written world, and vice versa. FTB is a compendium of crossovers.

This year Coudal is releasing the reviews as a bound book. Looks gorgeous, as does the poster and the process behind it. Kudos to Steve and the entire Coudal crew for editing such a cool volume. And for inviting me to contribute.

For geo-types, I’ve put together a quick map showing the geographical dispersal of the reader reviews. Some are guesses — for point-to-point air and road travel I used the midway as the location — and others don’t exist at all. Happy trekking!