CityFi

Much as I have enjoyed being a gentleman-of-leisure pack mule, fourth-rate interior decorator, and horrible default parent during the move to Denver, it is time to let you know what I’m up to.

I’ve co-founded a company with some of my favorite former colleagues. It’s called CityFi. If you’ve followed me here over the years you won’t be surprised to learn that we’re in the business of helping towns, cities, and metro regions become better places to live and work — whether that’s working for municipalities, urban design firms, architects, real estate developers, or the myriad of companies today whose products or services stand to improve urban life.

Full post over at Medium, but here’s the announcement part:

The CityFi team is a network of professionals who have implemented policies and projects at senior levels in government, foundations, and the private sector. Our team members have proven records of success delivering sustainable, significant change in the way cities work and the way people experience and participate in their communities.

We foster true partnerships that create value for people, for the environment, and for the economy.

We work with innovative global and local companies to deliver top-flight services that enhance the civic experience without imperiling the public good.

At its core, CityFi believes that great cities come not from monolithic projects but rather emerge from carefully-designed underlying conditions — street grids, equitable housing policies, business-friendly regulation — so that beneficial complexity can grow. This is how our most resilient, productive cities have grown for a very long time. We’d like to keep that growth going.

For more information on CityFi and what we do, visit our website and our Twitter feed.

This is an exciting time to be working at the intersection of technology, policy, and urban design. We’re (thankfully) past the techno-utopianist hype of the first wave of “smart cities”. Turns out the world hasn’t stopped urbanizing since then. Lots to do and couldn’t be more ready to get to doing it.

On Leaving Chicago

My family and I are leaving Chicago. I’d like to explain.

It’s simple: my incredible wife has been given a career opportunity that would be silly to let pass. The details aren’t really important. What is important is that the kids and I would do just about anything to support this woman. She’s on a rocket ship and we’re wired in at mission control.

For those of you who know me, this may come as a bit of a shock. More than a few of the few of you I have delivered this news to in person have expressed that you never thought I would leave Chicago. Well, I never thought I would either. I love this town to my core. I have written about that love over and over, went to work for the City of Chicago to try to make things better, and I’ve helped raise a family here.

But sometimes things change — and you never know what will happen. Back in 2000 when my wife and I were both working in Atlanta — newlywed, post-grad school, the very definition of unencumbered DINKs — unforeseen change also reared up. My wife’s company was being acquired and she was needed in Chicago. Honestly I was a bit worried. Chicago in 2000 was no tech mecca, especially compared to go-go late-90’s Atlanta. I specifically remember a BusinessWeek cover story from that year called “Chicago Blues” about how the town had lost its economic mojo. What, was I going to work for an agribusiness or something?

Obviously we did move and obviously things turned out very positively over the course of the next 16 years. Chicago’s tech bubble burst and then the scene reconstituted itself stronger than ever. I am the happy beneficiary of a move I initially did not want to make.

Oh, right: we’re moving to Denver. It’s gorgeous. It’s thriving. And, while I admit that Denver wasn’t ever on a short short list of cities I’d move to in a heartbeat, after a few visits I have no doubt it’ll be a great place to live.

So much more to say — even more left to do — before we depart this summer. Let’s not be strangers, now or in the future.

Shaping the tools

Pretty honored to be recognized by Newcity as one of Chicago’s “Design 50”. It’s quite a list to be on.

Photo by Joe Mazza

Here’s the accompanying write-up:

Some designers on this list design furniture, some the buildings the furniture goes inside of, and still others the blocks and developments we put those buildings in. John Tolva goes one better with his latest endeavor, designing the algorithms and systems behind the tools of urban planning. The one-time “data czar” for the City of Chicago has moved on to the private sector where he has been applying his data wizardry and impressive computer science chops in the development of urban planning and visualization technology. As Marshall McLuhan said, “We become what we behold. We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.” John Tolva is the man shaping the tools.

Here’s the full list.

I made the list in 2014 too and it contained one of the most unintentionally doleful photos I think anyone has ever taken of me. Glad the photo from this year (above) is the other end of the emotional spectrum.

Thanks, Newcity!

A year underwater

Last year, as Chicago settled into a colorless, lifeless winter freeze, I decided to take up Scuba diving seriously. Maybe it was escapism, envisioning myself floating above tropical reefs, the very opposite of the blizzardscape outside.

Great Barrier Reef, Cairns, Australia

There were other reasons for diving into an expensive hobby I had basically no time for. I suppose I’d finally come to terms with the fact that I would never actually be an astronaut. Diving seemed like a compromise. The sea’s a fairly alien world, as unmapped as the moon, and if you get your buoyancy right diving is about as close to flying (or bouncing around in microgravity) that I was ever going to get.

Poor Knights Islands, Tutukaka, New Zealand

It wasn’t completely out of the blue. I’d maintained a saltwater reef tank for about three years and had a more than beginner’s understanding of the complexity and beauty of marine ecosystems. Part garden, part science fair project, part sea creature death match arena: my reef tank was the gateway drug to Scuba. I was no longer content to sit outside the glass.

Molokini Crater, Maui, Hawaii

I knew going in I wasn’t interested in great depth. Not so fired up about shipwrecks. No desire whatsoever to jump through an ice hole or into mazy caves. I wanted coral reefs with all their bottom-up symbiosis and toxin-spewing brutality, exotic colors and improbable shapes, undulating tentacles and ship-slicing skeletons.

Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo, Mexico

Through luck, vacation time, and some trips tacked on to work travel I actually got to experience quite a bit this year: a sub-tropical way-stop of the East Australian Current at the tip of northern New Zealand; cliff-clinging life off the Amalfi Coast in Italy; the Crayola box coral gardens off Cozumel, Mexico; the mind-bending diversity of the Great Barrier Reef in Australia; and the playground of endemic species in Hawaii. Even did a wreck dive in the chilly but crystal clear waters (thanks, invasive mussels!) of Lake Michigan. Here’s a map.

The Wells Burt Wreck, 42.0458° N, 87.6180° W, Lake Michigan

There’s no way to make sweeping statements about the health of coral reefs with as (relatively) few dives as I made this year, despite the somewhat globe-spanning locales. But it certainly is true that reefs, like rainforests, are the coal mine canaries of climate change. I have personally wiped out entire ecosystems in my aquarium with two degree temperature changes. The ocean, of course, is far more resilient than a tiny tank, but it is clear that wild reefs themselves are under stress. We’re in only the third coral bleaching event in history and, while I saw some of the world’s best (and healthiest) coral, there was death and decay all around.

Cozumel, Quintana Roo, Mexico

It’s a wonderful world under the waves. Here’s hoping you get a chance to peek under them too sometime.

Near Praiano, Amalfi Coast, Italy

(The photos in this post link to larger versions which get you to fuller galleries. And if you’re interested, dive log details are available by clicking the place name in the photo caption.)

Art not ashamed to publish thy disease?

Twenty years ago I wrote a paper about the Internet. Let’s grade it.

1995. AOL, CompuServe, and Prodigy were the on-ramps to the Internet for most people. Geeks and university students surfed around via Telnet, FTP, Gopher and the still-new graphical web browser from the NCSA called Mosaic. Yahoo, Amazon, and Craigslist had just been born; Google was a year away. The Kindle was hard to even imagine.

I toiled in grad school, studying the cultural consequences of the spread of printing technology in England. But I was a computer nerd too and wholly smitten with hypertext, firstly the literary, non-networked variety you installed from floppies and then the new blue-underlined links on the World Wide Web. So I did what an unmarried, basically friendless grad student does on a topic of interest: I spent weeks working on a horribly convoluted, jargon-heavy paper about it.

The Heresy of Hypertext: Fear and Anxiety in the Late Age of Print was my embrace of electronic text and the nascent web. But that embrace was not really a discussion of the merits of hypertext. It was a critique of the critiques of the new medium — so very closed-loop and academia. In hindsight, a thoughtful analysis of what the Internet revolution might mean would have been way better, but then maybe I was presaging the web phenomenon of trolling the haters.

It’s painful to read, sodden with language from critical theory and words I made up out of whole cloth — “technoclasm”, “intraloquial”, what? — but I think I have managed to pull out the thread of argument. Let’s dissect and evaluate.

My starting position was that the printed word was on its way out. No timeframe, just that the slide was in progress. Probably seemed more radical in 1995 than I knew.

Despite exaggerated reports of its demise, the codex book is not dead — but, like handwriting in the age of print, it isn’t likely to remain the dominant means of textual dissemination. So the question is not if computers will transform our notion of reading and writing, but instead how?

True, in 2015 lots of books still get printed and read and, sure enough, newspapers are still around, but I think it is hard to argue that I got this one wrong. Though it is tough to quantify just how much reading takes place from a screen with the rise of higher-resolution displays, smartphones, and tablets, it seems obvious that the printed word has been toppled from its spot as Most Favored Medium. The question of what is being read or the quality of the print vs. online reading experience are other matters altogether, but I think this point has been proven over the last two decades.

So, on to the various anxieties I sought to shed light on:

Anxiety #1: Unmediated, unsystematized, instant access to information will make people dumb.

[Critics fear] that the non-hierarchical interconnectedness of hypertext represents little more than textual totalitarianism, implicitly proscribing what can and can not by read by the existence of a pre-defined nexus of links.

It is certainly true that total access to information is not the same thing as knowledge, though that has always been the case. Instant access to basically any information has been shown to promote confirmation bias and to enshroud us in filter bubbles — and probably contributes to the aversion to long online reads.

The critics were right to be skeptical. Hypertext-linked information does not make us dumb, but it does seem to amplify some of our human tendencies toward intellectual laziness. I’d argue this does not outweigh the benefits of access to the breadth of information available on the web, but my breathless cheerleading for “radically egalitarian” electronic text seems a bit shortsighted so many years on.

Thankfully, this part holds up:

… the circulation dynamic of texts published on the Internet resembles the medieval and Renaissance practice of glossing, parodying, or otherwise altering a manuscript before passing it along. Slowly, though, the ubiquity and fixity of print have eradicated such practices, all but banishing the notion of a collaborative, “textually permeable” work. Now, the cult of the author and the printing press are inextricably linked; you can’t have one without the other. Digital text, however, requires neither. As a consequence, and much to the chagrin of political critics, no economic model has yet been devised to explain its production and propagation in a capitalist society.

I wasn’t really thinking about journalism at the time, but it is true that we have yet to see a really viable business model for words on the web. The printing press gave birth to more than our modern concepts of authorship and copyright; it created a giant business model that we still haven’t properly modified or turned our backs on.

Anxiety #2: Digital text feels somehow different from printed text — and thus is bad.

… both Luddite and hacker agrees [sic — er, sic?] that a difference does exist. But if the same word inscribed on paper and displayed on a computer screen means the same thing — and how could it not? — then the only explanation is that we perceive a discrepancy, that the medium itself somehow affects how we think of the words.

Notwithstanding that the estate of Marshall McLuhan is probably owed royalties on that particular insight, it is obvious to nearly everyone now (as it was then) that there is an experiential difference between screen and paper. Reading on the Kindle most certainly does feel different than reading a book. Research has proven this to be the case with some concrete differences between paper and screen.

If I had an argument back then it was that this perceptual difference was not enough to dismiss electronic text as a medium altogether, which many critics did. I didn’t really back this up with anything, which may explain why I am not a college professor in 2015.

Anxiety #3: Electronic text, composed in graphical environments and often presented on screen intermixed with visual media, demeans the power of the word.

The upshot of critiques in this category is that words should be words, pictures should be pictures, and keep ’em separate. I cited hand-wringing over GUI-based word processing environments where “students who used word processors in the iconic environment of the Apple Macintosh wrote qualitatively and statistically inferior prose compared to students who composed on the text-based interface of IBM’s DOS machines”. That may or may not have been true then, but what’s interesting 20 years later is that, though we live firmly in graphical computer environments today, the pendulum for serious word processing has swung back, essentially acknowledging that visual distraction and excessive document customizability are at odds with serious writing. Programs like Scrivener and Ommwriter and entire window functions like OSX full-screen mode exist to address the problem of focus.

I did chuckle upon re-reading this passage:

[The] fear is not that future writers will revert to pictograms but rather that the traditional modes of textual composition that stress linearity, closure, and containment are being eroded from the inside out by the visually-based compositional aids themselves.

Turns out, the Internet in 2015 loves pictograms. I was being flippant back then, but with the ascendancy of emoji and the rebirth of animated GIFs it is hard to deny that word and picture are equal units of syntax in online writing.😐

The essay really says more about me than it does the Internet. If you can parse the byzantine prose you hear a kid full of excitement about a new medium, ready to make the jump from English grad school to Information Design. It was a thrilling time, though I’m left with nostalgia for a time when the web seemed so full of possibility and uncharted. It’s still a wilderness, but not for the right reasons.

The piece ends with this vignette:

In December of last year [1994], panic struck the Internet when rumor spread that a text-based computer virus was replicating its way across the globe and that it could be acquired simply by reading one’s electronic mail. For a while millions of people refused to approach their messages, afraid that the very act of reading would cause infection. We would do well to learn from this reaction, especially since the idea of a text-based virus was proven to be a practical impossibility; the rumor was a hoax. Indeed the rumor that the new medium of digital textuality will infect or corrupt our print-based practices is as baseless as the hysteria caused by the alleged virus. Human communication, like a living creature, has always adapted to tumultuous periods of change, surviving the “pathogenic” influence of speech, literacy, and moveable type, and no reason exists to think that it won’t adapt to the computer.

Viral infection from online reading was a joke in 1995 and for many years later (though many believed it was possible), but recently a bug was found to be exploitable in the Android operating system that allowed malicious code to take over a device simply by receiving a text message (technically MMS).

There’s still no need for panic; we adapt, as we always have. And that’s the argument of “The Heresy of Hypertext”, minus 3,806 words.

Cena Lucana

May 20 was the Day of the Lucani, a completely made-up, sparsely-documented celebration for people whose ancestors can be traced to the lonely region of Basilicata, Italy. This roughly triangular province, called Lucania by ancient Greeks, is the instep of the boot of Italy, a mountainous, relatively arid landscape sandwiched between the Tyrrhenian and Ionian Seas that Norman Douglas called “the Sahara of Italy” in 1915. My great-grandparents came to America from this region in 1903 — as did very many of their compatriots. So much so that in the early part of the 20th century the volume of émigrés exceeded the birthrate.

I’ve visited Basilicata three times (and written a lot about it), meeting people along the way each time. A few weeks ago my friend Daniele Bracuto, a designer from my great-grandparents’ village of Barile, posted a menu exclusively comprised of specialities from that small town.

This is remarkable for a few reasons. First, though many (most?) Italian-Americans can trace their roots to Southern Italy, there is a dearth of cookbooks from there. (Sicily is an exception.) One might attribute this to America’s continued fascination with all things Tuscan, but the truth is that even today there is a real ignorance of Italian culture south of Rome. Christ stopped at Eboli and apparently so did the cookbook authors.

The other reason this is exceptional is that Barile is a tiny place, known really only for three things: 1) an extraordinary wine called Aglianico del Vulture; 2) its position on the slope of a majestic, extinct volcano; and 3) that its citizens lived in caves carved from limestone into the 20th century. Food, you will note, does not distinguish Barile (or, really, Basilicata — there is a reason many Southern Italian dishes use hot peppers). But I was wrong about that and I had a menu to prove it.

Daniele sent me the chefs’ recipes. They were in Italian (of course), some Arbëreshë (I think), and scaled to serve many dozens of people. There was no way I was not going to make it, terrible translation and portioning be damned.

Now, I have been practicing cooking as ancestor worship for a long time (here’s Spaghetti All’assassino, scorched wheat pasta, and Carbone Dolce). But this was a challenge above and beyond. I headed to Eataly in Chicago for expert help. For one, I was looking for tagliatelle mollicate, a kind of thick, serrated linguini I had never heard of. But Antonio, the legit paisan pasta monger at Eataly, knew of it and called it “reginelle” pasta. But Eataly did not carry it, so … he made it, by hand, with a zig-zag cutting tool!

Suffice to say there was a lot of improvisation. I chose two of the four courses from Daniele’s menu. The pasta dish and a cod and bean puree dish. Recipes are included below in Italian lest you make fun of my translation. Original proportions. Run it through Google Translate if you want a real laugh.

Tumact Me Tulez

(Tagliatelle mollicate con sugo alle noci ed alici)10 kg di reginelle

5 kg di mollica di pane

2 vasetti da 500 grammi di alici

16 kg di pelati

2 kg di noci puliteProcedimento:

Preparare il sughetto con olio aglio e separatamente tagliare le alicette a pezzettini ed immergerle nel soffritto. Aggiungere il pomodoro e portare a cottura. A parte in una padella fare tostare i gherighi di noce con la mollica di pane e un po’ di olio fino a farlo diventare croccante. A fine cottura aggiungere una spolverata di prezzemolo. Cuocere la pasta e saltare in una parte del sughetto aggiungendo un po’ di mollica aromatizzata. Impiattare aggiungendo uno o due cucchiai di sugo ed abbondante mollica di pane.

Duo di baccalà su passatina di fagioli di sarconi e peperoni cruschi di Senise

Baccalà 20 kg ammollato

7 kg di fagioli

1,5 kg di peperoni cruschi

2 kg di patate a pasta gialla

250gr di lardo

100 cialde di pane

Timo, Rosmarino, cipolla, prezzemolo, Alloro, peperoncino, aglio.Procedimento:

Baccalà: Spellare il baccalà, togliere la pelle e tagliandola a triangolini farla cuocere in forno con un filo di olio fino a farla diventare croccante per guarnizione. Tagliare il baccalà e creare 100 pezzi di 4cmx4cm circa l’uno, cucinare sottovuoto al 50% unendo timo, poco olio e pepe, cucinando a vapore a 80° (forno a temperatura controllata) se non ha il forno con buste per cottura in acqua quasi al bollore. A parte utilizzando la parte rimanente del baccalà (NB utilizzare le parti più alte del baccalà per i 100 pezzi e le parti più basse verso la coda per la pallina di baccalà), cuocere a vapore controllato sempre con timo olio e pepe e a fine cottura frullarlo insieme alle patate lesse e servire le palline con una pinza pallina gelato.Fagioli: Mettere a bagno i fagioli la sera prima, successivamente scolarli e cucinarli in acqua con poco sale e qualche foglia di alloro. A parte fare un fondo con cipolla tritata, poco peperoncino, un rametto di rosmarino e del lardo. Levare il rosmarino ed unire i fagioli cotti precedentemente. Lasciare insaporire ed aggiustare di sale e pepe. Utilizzare una parte di fagioli interi guarnizione e la restante passarla al passatutto. In fase di guarnizione utilizzare il peperone crusco.

It turned out quite well, all things considered. The sauce for the pasta had the slightest hint of anchovy and a somewhat stronger hint of red chili and the serrations of the pasta held it nicely. The cod/potato mash on top of the bean puree combined for a flavor I had never experienced.

But this is only part one. The real delicacy from the menu I am excited to make, Zuppa dei Brigante (“Brigand Soup”) awaits. For now, though, I have a flight to Italy to catch. Ciao!

What we talk about when we talk about smart cities

About a century separates the two Scientific American covers above. We’ve been talking about “smart” cities for a long time.

Maybe not in so many words, but the idea of designing a city to optimize it, to make it more efficient, to make its uses more intelligent far pre-dates digital technology. Sometimes the term is at the forefront of urban rhetoric and marketing — during election cycles or after natural disasters, for instance, or when new industry entrants smell a market opportunity.

And sometimes the idea recedes a bit. Recently we’ve seen outright hostility to “smart cities”.

But no matter when we’re talking about smart cities we often do so in terms of particular systems or projects. This city is smart because of its low-carbon transit network. This city is smart because of its waste-to-energy plant. This city is smart because of its predictive policing. And on and on. Or, as above, we can put together top ten lists of projects that will make your city smart. Projects that are so tied to specific new technologies they will either fail or be obsolesced by the volatility of technological change.

A more useful way to talk about smart cities might be to ask questions of a different type. What approach do they take? What is their philosophy of smartness? Who does it benefit in the long run? Below I describe some of these philosophies with design case studies. Though many of these examples are rooted historically, they are not necessarily linear in time — they overlap, circle back, and pop up dressed differently.

The clockwork city is the conception of metropolitan operations most familiar to people. It is an Enlightenment view of the city as a literal machine. One that can be measured, whose gears can be oiled, whose job it is to produce efficiency. It is an engineer’s view of what makes a city work. The city as sum of its infrastructure and services.

One way to understand the clockwork way of thinking is to use the example of public buses. A clockwork view poses the matter of buses as an exercise in operational performance: How can we manage our buses more efficiently? This of course has led to innovations such as timetables. It is an infrastructure-focused view that prioritizes the operator’s needs — essentially asking, in this example, how can we know when buses are supposed to be at a given stop?

There’s nothing wrong with this operational approach, of course, and indeed it has dominated city management for a very long time. What’s useful is to note how this view is the singular focus of most modern “smart city” campaigns, especially with regards to how enterprise technology firms view the challenges in front of a city. Wanting to know where your buses should be is the seed that grows into citywide command centers powered by top-down, command-and-control technologies (such as the one pictured above in Rio). It has been called Dashboard Governance.

There have been many attempts at this kind of smart city. Most are developments from scratch or adjacent districts of established towns. Because ecological sustainability is in theory a more easily quantifiable axis of a city than, say, homelessness or income equality, energy is usually the centerpiece of these types of smart cities. Most have not lived up to their marketing.

There’s a different philosophy of the smart city and it has been driven by the move in recent years to open up city data to the public. Initially undertaken as a political corrective to decades of opaque systems and hard-to-FOIA documents, the open data movement in cities has grown beyond transparency to cities that use it to enforce accountability in its workforce, to analyze patterns and trends for policy interventions, and even as a starting point for companies to add valuable services upon. Open data as economic development.

Using the bus analogy again, instead of the city telling commuters when a bus should be where, an open city approach to design let’s people ask: How can I know where and when a bus will be available? It may seem a subtle distinction, but the difference is enormous. The open city puts the user of the system — in this case the city-dweller — at the center. Decision-making control, if not operational control, of the system moves from inside government to outside.

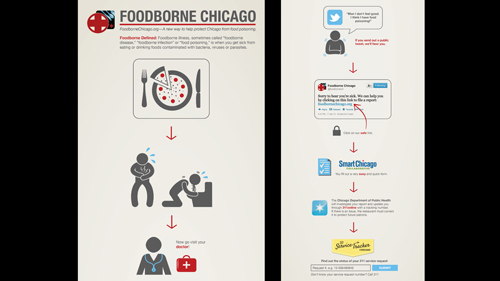

Examples of open city design from the civic tech movement are plentiful. Above, Foodborne Chicago uses public tweets (generated by people totally unconnected to the public health department) to determine whether an instance of food poisoning has occurred.

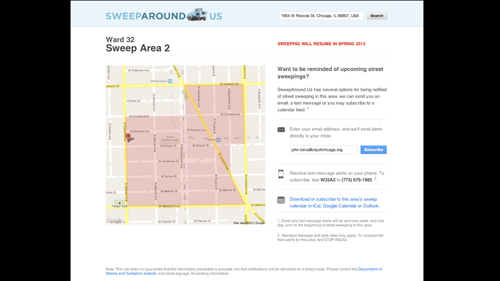

SweepAround.us takes somewhat inscrutable public data about when ticketing will be enforced for street cleaning and proactively alerts residents when they need to move their vehicles.

The open philosophy of the smart city above all focuses on making the city more legible; it isn’t necessarily about citizen-government interaction but about allowing those who live in cities to situate themselves at the center of systems — making sense from the vantage of their personal needs and uses.

The newest perspective is what might be called the emergent city. In this framework initiatives are aimed at changing the underlying conditions that lead to a system’s functions, rather than the system itself. It takes the constituent pieces of the urban experience (whether run by the municipality or not) and joins them loosely through technology to generate different outcomes.

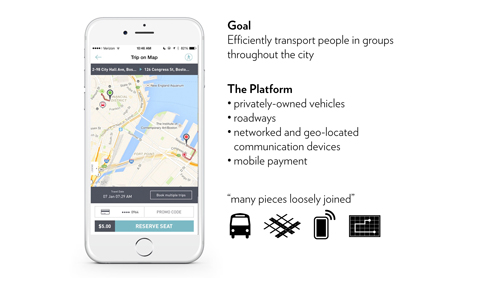

The bus example is again useful. An emergent approach, one that we might also call city-as-platform, asks not when or where a bus is, but rather “What if any vehicle could be a bus?” Typically cities address outcomes, in this case moving people around, but emergent city design seeks to change the initial parameters of a system and let complexity grow from that.

If the goal is to efficiently transport people in groups throughout the city, a centralized bus service is one way to do it. But thinking of mobility as a platform, we can also tally the constituent parts — here, privately-owned vehicles, roadways, networked personal devices, and mobile payment — and ask how they might be made to generate the same outcome as public buses. The example of the Boston company Bridj above is one effort at accomplishing this.

This isn’t about privatizing services so much as it is rethinking a city’s assets — public and private — when overlaid with network technologies. It’s the “sharing economy” with a civic bent: what happens when urbanism focuses on recombinant uses of space and infrastructure. A technologist might call it experimentation-as-a-service.

Projects such as Hello Lamp Post out of Bristol, England have this philosophy in mind as it uses street furniture to prompt local, place-based storytelling. The addition of network technologies to traditional aspects of the cityscape is what allows for the emergence of new uses of the city, new behaviors for its dwellers.

While IT companies push for Internet-aware devices (the “Internet of Things”) largely in the pursuit of operational (clockwork) efficiency, the networked city also offers the possibility of new bottom-up solutions. The Array of Things is a non-governmental project aimed at providing hyperlocal environmental data to whomever wants to use it. (One envisioned use case is to provide information about ice patches that have formed on sidewalks block-by-block.) In both examples, what’s different is that traditionally monolithic infrastructure is atomized and offered up for reuse. Hello Lamp Post and the Array of Things are not solutions to city challenges per se. They change the initial conditions of a system, allowing complexity and the creativity of the urban populace to make something from them.

It’s tempting to think of these three frameworks as evolutionary, one building upon the other. But they are not. There are aspects of all three consistently rubbing up against one another in most cities today. And it is difficult to categorically say that one view is better than another, for that distinction requires acknowledging who the approach benefits. Being smart about smart cities requires asking ourselves who is defining what smart is and who might be sidelined by that definition.

Hive architect

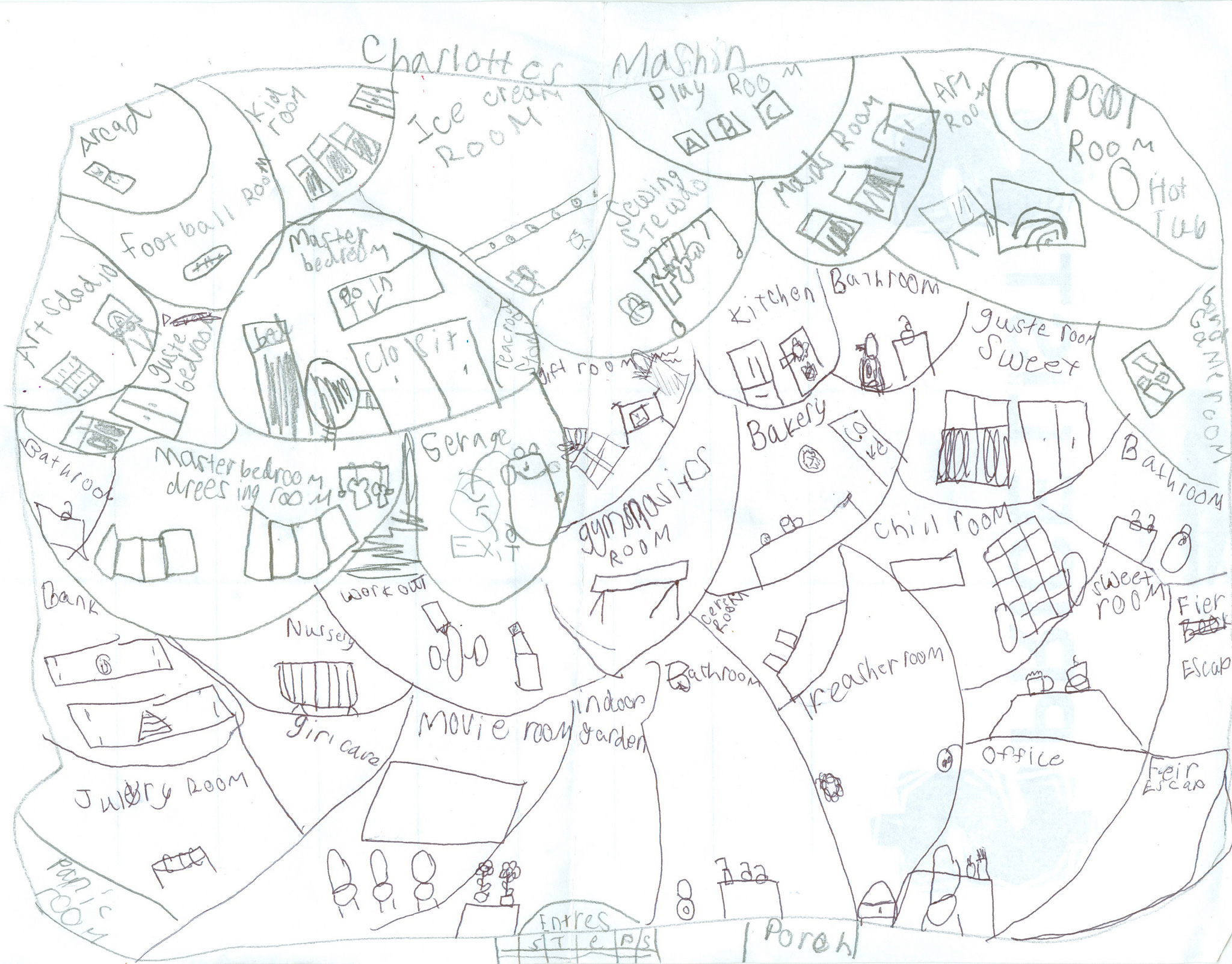

My daughter is obsessed with designing houses, architecturally. I love it, but there’s room for logic of any kind improvement.

Notes:

- Natural light? This architect is not a fan.

- Panic Room on an outside wall = security problem!

- Somewhat uneven distribution of Fire Escapes (and it’s a one-story house).

- Garage in the middle of the house is accessed via an “underground tube”.

- The house has its own Bank, which is not to be confused with the Treasure Room.

- Girl Cave!

- Two Art Rooms, presumably in case one is filled with terrible ideas.

- No Kitchen, but it does have a Bakery, Sweet Room, and Ice Cream Room. UPDATE: I missed the kitchen. It’s there!

Click image for larger version.

Looking for a house manager/nanny

We’re in the market for some help. If you fit the description below or know someone who does, please get in touch.

Busy Roscoe Village family seeks energetic, experienced, self-directed full-time house manager.

Individual should be a non-smoker, have own transportation and mobile device, and be comfortable with email, texting, and web-based services (e.g., classroom websites, school lunch ordering, activity registration) necessary to run this active family. Three children, ages 8, 11, and 13, are in school full-time M-F, but need after school care. Full-time working parents need help managing the house.

Flexibility to run errands, willingness to perform light housekeeping and organize small projects, and ability to maintain active extra-curricular schedules for the kids are a must. 40-45 hours/week, split between time with children (school dismisses 3p, most days) and time to help around the house and run errands.

Daily hours have flexible start time, and parents cover “morning shift” most days. Ability to work longer hours or overnight when both parents are traveling, or entire days (when school is out, or kids are sick) is optimal.

If you fit this description, are available immediately, and can provide strong references we look forward to hearing from you!

Giftmix 2014

Some select tunes that I enjoyed this year. I hope you do too. Happy holidays and a healthy, prosperous new year to everyone.

Tolva Giftmix 2014 by Immerito on Mixcloud

Hawkmoth – Plaid

Awake – Tycho

minipops 67 [120.2] [source field mix] – Aphex Twin

I Take Comfort In Your Ignorance – Ulrich Schnauss

Quincy – Deep Dish

Pole Position (Gran Prix Version) – Der Dritte Raum

Higher Ground – TNGHT

Canis – Theorem & Sutekh

Mimas – X-102

101 rainbows ambient mix g1 – Caustic Window

Full stream at Mixcloud, above. File for download here (114MB). Previous mixes here.